Featured Articles

Damon Feldman, the `16 Minute Man,’ Aims to Bring His Wild Story to Silver Screen

What do Jose Canseco, Tonya Harding, Rodney King, Danny Bonaduce, Joey Buttafuoco, Lindsay Lohan’s father, Vai Sikahema, El Wingador, Octomom, a semi-notorious Philadelphia TV meteorologist and an aging Philly sports writer attempting to channel his onetime inner tough guy have in common?

At first glance, most people outside of Delaware County, Pennsylvania, would conclude there couldn’t possibly be a link attaching such disparate individuals. But that assumption would be incorrect.

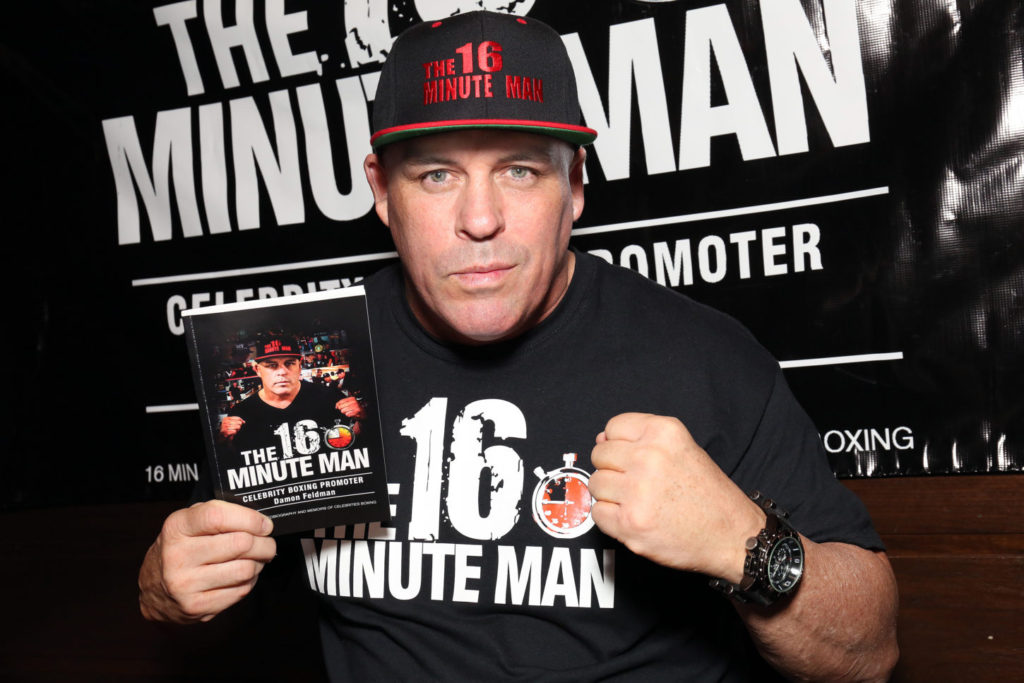

Meet Damon Feldman, the undefeated former super middleweight turned Celebrity Boxing huckster and unifier of all those seemingly mismatched parts. Once labeled “King of the D-List” in a Philadelphia magazine article that was something less than complimentary, the now-44-year-old Feldman is aiming for an alphabetical upgrade to another title of sorts, possibly “King of the B-Flicks.” Earlier this month he hosted a gathering at a Drexel Hill, Pa., restaurant that drew two media members (I constituted half of the press corps) and about 50 prospective donors for the movie he intends to make about his occasionally tragic, sometimes infuriating, relentlessly optimistic and thoroughly improbable life.

If enough well-heeled backers can be brought on board, 16 Minute Man, the same title as Feldman’s 2017 book that never made it onto the New York Times bestseller list, will reach silver screens nationwide sometime in 2020. He hopes to raise $50,000 in developmental money, a tiny acorn which, if all goes as planned, will transform into the mighty $5 million to $10 million oak he said it would take to make the film – if it actually advances beyond the theoretical — as much as a commercial and critical success as 2010’s The Fighter, the tale of scrappy “Irish” Micky Ward and his drug-addicted brother-trainer, Dicky Eklund, which was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won two.

“Jackie (Borock) and Scott (Weiner) were doing a documentary on me,” Feldman noted. “After watching Mark Wahlberg’s movie about Micky Ward, who no doubt was an accomplished fighter, I thought, `I really do have a story to tell, too.’ I wrote my book in jail (more about that later), Jackie jumped on board and, well, here we are.”

But, meanwhile, the show must go on. Feldman – that “16 Minute Man” moniker refers to the 15 minutes of fame avant garde artist Andy Warhol once predicted everyone in the future would have – figured quasi-celebrities whose time limit as public figures had expired might need some fast cash or an ego boost that would accompany a bit of renewed exposure. Those sufficiently desperate for either or both reasons thus were susceptible to the sales pitch thrown by a natural self-promoter whose thwarted dream had been to become a world champion fighter. But harsh reality has a way of sometimes morphing lofty ambition into something less grandiose. Feldman’s 68th Celebrity Boxing card will take place on June 8 at the Showboat Hotel in Atlantic City, with the main event pitting Natalie Didonato, most recently seen on the reality TV show Mob Wives, against female pro rassler Scarlett Bordaux. In the on-deck circle for June 29 in Los Angeles: Mark Wahlberg’s best friend Henry “Nacho” Laun, featured on still another reality TV series, The Wahlbergers, vs. Megan Markle’s half-brother, Thomas Markle Jr.

Just who would pay to see such low-rent matchups? Well, probably more than might be imagined. Rubber-neckers inevitably gather to see barroom brawlers or schoolyard kids go at it, and the stakes are hiked if the punch-throwers have retained even a thin vestige of fame or familiarity.

For Feldman, his legitimate goals sidetracked, the realization of the different course his life was about to take came after he was obliged to retire as an active boxer.

“I took odd jobs. I was down the (Jersey) Shore one weekend and saw these two guys fighting, a bar fight, and I thought, `We should do this in the ring,’” Feldman recalled in the Philadelphia magazine article authored by Don Steinberg which appeared in the December 2009 issue. His start was relatively modest, the staging of a Tough Guy tournament which drew eight participants of varying skill levels and 500 or so spectators for the one-night event. After expenses were paid and a winner announced, Feldman came away with a profit and the notion that what worked once would work again, and bigger, if presented as outrageously as possible and with a loquacious front man – himself –serving as carnival barker.

In retrospect, Feldman probably was destined to spend a large chunk of his life in some form of boxing. Son of noted Philadelphia trainer Marty Feldman, his interest in the fight game and his inevitable place in it spiked when he was one of the “Faces in the Crowd” featured in the Aug. 15, 1983, issue of Sports Illustrated. There on page 69 was a photo of the then-13-year-old Damon and a caption that read: Damon Feldman, Broomall, Pa. Damon, 13, scored a second-round knockout of Joe Antepuna to win the Philadelphia Junior Olympic boxing title in the 13-and-under 112-pound class. He has been boxing since age five and has an 8-1 record with two KOs.

There was never any question that Damon, who was and still is billed as the “Jewish Rocky,” would continue to hone his craft and assume his rightful place in the family business as a pro. Maybe, if he could just catch a break, he could go even further than his dad, who fashioned a 20-3 record with 17 KOs as a hard-hitting middleweight before transitioning as a trainer, most notably as the chief second of world-rated brothers Frank “The Animal” Fletcher and Anthony “Two Guns” Fletcher, as well as IBF light heavyweight titlist “Prince” Charles Williams. Also bearing the Feldman imprimatur was Damon’s older brother David, five years his senior, who would go 4-1 with four KOs before hanging up his gloves.

Damon’s history – his mom, Dawn Feldman, who had divorced Marty, was brutally attacked by an unidentified assailant shortly after their divorce in 1974 and suffered a broken neck that left her a quadriplegic – and ethnicity made him a popular and sympathetic figure as he stitched together a 9-0 record that included four KOs. Only four years old at the time his mother was assaulted, Damon and his brother never lived with her again. It speaks well of the now-deceased Dawn that, despite her physical limitations, she became something of an artist and poet despite spending most of her remaining years in rehab facilities. Nor was she the only victim of a horrific crime that was never solved; for the next six years, until they moved in with Marty, who had been struggling to earn a living, Damon and David were human pinballs, bouncing around to three different foster homes.

Was Damon good enough to someday rise above undercard status at the Blue Horizon? He says yes, definitely. “All I ever wanted to be was a world champion,” he said. “It was my hope and dream to drive down to North Philadelphia every single day and train in the same gym as Bernard Hopkins, Robert Hines and all those guys. I wanted that belt more than anything.”

Feldman’s promoter, J Russell Peltz, said he tried to pair the likeable local kid with beatable opponents, but it would take a leap of faith to imagine him seeing his world-championship dream through to fruition. Nor is Peltz the biggest fan of Feldman as the face of low-grade Celebrity Boxing. “Damon has always been more about promoting himself than his events,” Peltz is quoted as saying in the Philadelphia magazine story. “He’s more about the sizzle than the steak.”

Whatever Feldman could have been as a fighter became a moot point when he slipped outside a grocery store in Broomall and took a nasty fall. “The curb broke as I walked off it and I just fell,” he recalled. “I hit my neck and my head, messed my disk up.” He never fought again, at least in a sanctioned bout, and, despondent and angry about his adjusted circumstances, entered into what might be described as the infuriating and reprehensible phase of a topsy-turvy existence.

Although he tried his hand at promoting legitimate fight cards, five of which came off, Feldman proved to be less than an exemplary businessman as well as something of a loose cannon. He began drinking more heavily until it became a problem, although he is adamant in refusing to state he is or ever was an alcoholic. His promoter’s license was revoked by the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission when, in 2005, an argument over tickets and money at a pre-fight meeting turned violent. The other promoter placed his hand upon an increasingly agitated Feldman, who scored a one-punch knockout with a left hook.

Even worse, in October 16, 2016, he struck a woman, with whom he had been involved romantically, several times with a closed fist and enough force that police, upon arriving at her home, found her bleeding from the nose, head and face.

Feldman served 13 months of a two-year jail sentence after pleading guilty to simple assault and recklessly endangering another person. He now says the incident that led to his incarceration was the “stupidest mistake of my life, but I learned from it and I came back. I’m not a quitter.”

So why is Feldman, who said this most recent redemptive chapter of his thick volume of ups and downs owes in large part to his parental devotion to his 12-year-old son and 16-year-old daughter, still as much or more of a celebrity as the D-Listers who populate his fight cards? It might be because, warts and all, he’s essentially an impassioned salesman of himself and his brand. He has been a guest on Howard Stern’s nationally broadcast radio program, at last count, 10 times and on Philadelphia drive-time sports station WIP, hosted by Stern’s Philly equivalent, Angelo Cataldi, perhaps 10 times that. Former Philadelphia Daily News gossip columnist Dan Gross regularly featured references to Feldman and any of his off-the-wall gimmicks because what else is a gossip column about?

Feldman’s first foray into Celebrity Boxing, in 1997, was limited in scope, the main event pitting Diego Ramos, a Philadelphia disc jockey, and John Bolaris, a weatherman for a Philly TV station. But Bolaris, a good-looking guy who got frequent mentions in Gross’ gossip column for his man-about-town squiring of a steady stream of beautiful and high-profile women, was the prototype of the type of participant Feldman knew could fill a 500- to 800-seat room. Bolaris would have been an even more surefire draw if his appearance had come 13 years later, when he was drugged by a couple of Russian bar girls working for an international crime syndicate in Miami’s South Beach. Seeking to confront the women, Bolaris met with them again, was slipped another roofie and awoke hours later with a pounding headache and $43,000 worth of charges on his American Express card. He contacted law enforcement officials, which led to 17 arrests, but instead of being hailed as a hero for the busting of so many nefarious types, as Bolaris had hoped, he was roundly derided for finding himself in such a humiliating situation and was fired by his station.

In other words, Bolaris at almost any stage of his television career was just the sort of “celebrity” that Feldman has sought out like a heat-seeking missile.

“I was a young guy, suffering and depressed,” Feldman said of his state of mind after his boxing career ended and his promoter’s license yanked. “Doing Celebrity Boxing shows became, like, my high. I just loved doing what I was doing. Anybody whose name was in the tabloids I tried to get in my ring. It’s like my nickname. I try to give all of them their 16th minute of fame.”

For appearance fees ranging from $1,500 to $5,000, Feldman has successfully enticed a string of down-on-their-luck notables to swing away at others of their ilk. Even when he failed to make sensationalistic bouts that were purposefully leaked to the media, he got the kind of publicity that promoters of “real” boxing would kill for. He attempted to pair Rodney King, the “Can’t we all just get along?” victim of a 1991 beatdown by Los Angeles cops, with one of the police officers involved in the incident, which drove the Rev. Al Sharpton to near-hysterics. The LA cop didn’t participate, but King mixed it up with an ex-cop from Chester, Pa., Simon Aouad, whom King defeated.

Another proposed fight that got lots of media attention but didn’t happen would have pitted Marvin Hagler Jr. against Ray Leonard Jr., the non-boxer sons of legendary fighting fathers. But it’s not just the near-misses with which Feldman has generated headlines; his most successful promotion to date was a matchup of Canseco, the steroid-fueled slugger of 462 major league home runs and the author of a tell-all book which outed Oakland teammate Mark McGwire as a fellow juicer, and a grown-up Bonaduce, the freckle-faced, red-haired kid everyone remembered from his time on TV sitcom The Partridge Family. Canseco seemingly got the better of Bonaduce, a friend of Feldman’s, over three rounds, but the fight ended in a controversial draw (even Celebrity Boxing outcomes apparently can be disputed), leading to accusations that the fix was in.

Canseco, maybe more than any Celebrity Boxing contestant, is associated with Feldman. The large and heavily muscled former baseball player, at 6-foot-4 and 240 pounds, unwisely consented to duke it out in 2008 with former Arizona Cardinals and Philadelphia Eagles punt returner Vai Sikahema, who celebrated his touchdowns by whacking away at padded goal posts as if he were still the kid from Tonga who had been groomed by his father to become a champion boxer until he decided he liked football better. Sikahema, a two-time Pro Bowler who was then a sports director for a Philly TV station, tore into the much larger Canseco like a famished lion going after a stricken wildebeest. “I think I can safely say that 105,000 Tongans are well aware that I am fighting Jose Canseco,” Sikahema said before the bout. “I do not intend to disappoint them.”

Perhaps remembering the thrashing he took from Sikahema, Canseco, who was scheduled to appear in the main event of a 2011 Feldman-promoted event in Atlantic City, chose to stay home and sent identical twin brother Ozzie to fight in his stead. The ruse was immediately apparent when Ozzie stripped off his shirt and his upper-torso tattoos were different from Jose’s. The fight was called off and Feldman sued Jose for breach of contract.

Feldman also was instrumental in Celebrity Boxing making it all the way to network television in 2002, with Fox airing two hour-long episodes featuring celebs who were a cut above D-Listers, at least in terms of how famous they once had been. In the first installment, Bonaduce floored Greg Williams, of The Brady Bunch, five times before Williams’ corner threw in the towel in the second round. Tonya Harding, the disgraced figure skater who also fought for Feldman, had her way with a clearly frightened Paula Jones, alleged consort of former President Bill Clinton, who at one point attempted to hide behind the referee. Jones surrendered in the third and final round, allowing Harding to skate away with a TKO victory.

But it was a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not matchup in the second installment that had to qualify as the most memorable Celebrity Boxing bout ever. In one corner was ultra-skinny former NBA center Manute Bol, all 7-foot-7 of him, against 400-pound-plus former NFL defensive lineman William “The Refrigerator” Perry. The Fridge basically ran out of gas moments after leaving his corner for round one, but he somehow stayed on his feet to the final bell, eating a smorgasbord of jabs from Bol, whose 102-inch reach might have been more incredible than his height.

Although TV Guide ranked Celebrity Boxing on Fox No. 6 on its “50 Worst TV Shows of All Time” later in 2002, Feldman takes pride in having had a hand in it. “I worked out a deal with (Fox) because it was my concept,” he said. “They only did the two shows, but they did pretty good numbers. After that I just continued to do my own thing.”

Full disclosure: I did a Celebrity Boxing turn for Feldman in July 2002, for no compensation, with any money I would have received going to the Don Guanella School (now closed) for intellectually disabled children. My opponent was Philadelphia attorney George Bochetto, a former commissioner for the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission best known in boxing circles as the lawyer who represented former heavyweight contender Randall “Tex” Cobb in his libel lawsuit against Sports Illustrated, which resulted in a $10.7 million judgment for Cobb, later overturned on appeal. Bochetto – younger, leaner and a guy who regularly trained as a boxer three or four days a week – had everything going for him. But I was the son of a left-hooking former welterweight, and I wanted to see what, if anything, I had left. I did not inform my wife of my intentions until it was announced in my newspaper, which led her to ask, at a higher decibel level than I’d ever heard from her, “Are you nuts?”

George preferred to fight at a distance that suited him, and he was more accurate than I expected with the overhand right. But I bored in at every opportunity, trying to force him to the ropes and unloading left hooks and uppercuts with both hands. In effect, he was making Muhammad Ali moves and I was doing my best Joe Frazier impersonation. The split decision went to George, but the judge who had me ahead, the late, great Jack Obermayer, had been ringside for thousands of fights so I’m always going to think I really won.

Win or lose, though, my wife told me I was retired forever. Probably a wise decision on her part.

For those interested, more information on the movie project can be found at 16minutemanmovie.com.

Bernard Fernandez is the retired boxing writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. He is a five-term former president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, an inductee into the Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Atlantic City Boxing Halls of Fame and the recipient of the Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service to Boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers