Featured Articles

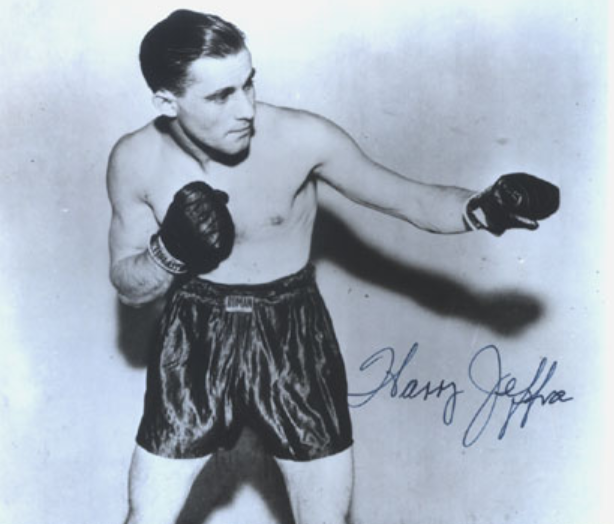

Gervonta’s Baltimore Homecoming Awakens Echoes of Harry Jeffra

Seventy-nine years ago this coming Monday (July 29), Baltimore native Harry Jeffra successfully defended his featherweight title with a 15-round unanimous decision over Toronto’s Spider Armstrong. This match — refereed by The Ring magazine founder Nat Fleischer – is being recalled as the last world title fight held in the City of Monuments in which a local man defended his title….until tonight, that is, when Gervonta Davis defends his World Boxing Association Super World Super Featherweight Title (that’s a mouthful) on SHOWTIME in an apparent soft defense against Panama’s unheralded Ricardo Nunez.

Harry Jeffra was very good and had a legitimate claim to the world featherweight title, but as title fights go, Jeffra vs. Armstrong warrants an asterisk.

No, there weren’t four international bodies vying for supremacy, but things back then were just as muddled. When Jeffra entered the ring that night, he was one of three recognized featherweight champions. The National Boxing Association (forerunner of the WBA) recognized Petey Scalzo. The New York and Maryland (and eventually Pennsylvania and California) boxing commissions recognized Jeffra. The Louisiana commission was partial to Jimmy Perrin. And overseas? Well, let’s not go there.

Harry Jeffra, who was Sicilian on his father’s side, was born in Baltimore on Nov. 30, 1914. His birth name was Ignatius Guiffre. With a name like that, it was inevitable he would adopt a different ring name, but folks knew him as Harry Jeffra before he ever laced on a pair of gloves. The name was applied to him by his schoolteachers who couldn’t pronounce Guiffre.

Jeffra was born in the shadow of Baltimore’s Pimlico Racetrack and in some of his early fights was billed as the Pimlico Kid. Ironically, in retirement, after working as a jockey’s agent, Jeffra became a stable manager at the fabled racetrack.

Turning pro at age 18, Jeffra had his first 39 fights in Baltimore with the exception of four excursions to nearby Washington, DC. He attracted national notice late in this run with a 10-round split decision over Puerto Rico’s Sixto Escobar, the generally recognized world bantamweight champion.

Jeffra and Escobar would meet five times; Jeffra winning four. The third and fourth meetings were stamped as world title fights. The finale, in Baltimore, would be Escobar’s final pro bout.

Escobar-Jeffra III was staged on Sept. 23, 1937 at New York’s Polo Grounds as part of the “Carnival of Champions” in which four title-holders risked their belts on the same card. Lightweight Lou Ambers and welterweight Barney Ross prevailed against Pedro Montanez and Ceferino Garcia, respectively. Middleweight title-holder Marcel Thill was upended by Fred Apostoli, the San Francisco Bell Boy (although New York continued to recognize Freddie Steele; go figure) and Harry Jeffra got things started by dethroning Escobar, winning a lopsided 15-round decision. “He buzzed around him like an angry hornet in a fight that was full of action,” said the correspondent for the New York Times.

Promoter Mike Jacobs anticipated a crowd of 50,000, but the announced attendance was only 32,600. Many boxing fans hadn’t yet recovered from the Great Depression and all sorts of amusements were in the doldrums.

Five months later, the Baltimorean and the Puerto Rican met up again on Escobar’s turf in San Juan. In this bout, Jeffra bore scant resemblance to the fighter that won their three previous meetings. He was knocked down twice in the 11th and once in the 14th and finished the contest with both of his eyes nearly closed. The announced attendance at the outdoor show was 12,000, but promoter Mike Jacobs, a whiz at creative bookkeeping, claimed that the gate receipts totaled only $13,900.

Jeffra had struggled to make weight for Escobar IV. Seven months later he returned to the ring as a featherweight and after adding eight wins to his ledger was pitted against veteran Joey Archibald who held a share of the fractured featherweight title. It was the first defense for Archibald who had won the belt in his hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, with a 15-round decision over Chicago’s Leo Rodak.

Archibald was managed by wily Al Weill who later handled the ring affairs of Rocky Marciano. Washington, DC was Archibald’s second home. Prior to his Sept. 28, 1939 bout with Harry Jeffra at Griffith Stadium, he was 18-0 in DC rings.

The skein continued with Jeffra losing a split decision that nearly caused a riot. Spectators booed for a good 15 minutes after the verdict was announced and pelted the ring with debris. It was a harrowing experience for ring announcer Jimmy Lake who couldn’t leave his post as the semi-main had been pushed back to the walk-out fight.

Jeffra got his revenge eight months later in Baltimore. He nearly had Archibald out in the second round but the Providence man stayed the 15-round limit only to lose a lopsided decision. Jeffra’s first defense against the aforementioned Spider Armstrong would stand for almost 80 years as the last winning effort by a Baltimore world title-holder in a Baltimore ring. He gave back the belt in a third meeting with Joey Archibald, another disputed split decision at Griffith Stadium, although not as contentious as the first, and then failed in an attempt to regain the title when he was stopped in the 10th frame by Archibald’s conqueror Chalky Wright.

After losing to Wright, Jeffra soldiered on for a few more years before retiring at age 32. A short-lived and unproductive comeback after a 44-month absence dipped his final record to 94-20-7 (per BoxRec). Although the titles he held were in dispute at the time that he held them, he passes the lineal test as a two-division world champion. The late Hank Kaplan, who was considered the foremost historian of the Sweet Science, is among those who believed that Jeffra did enough to warrant inclusion in the Boxing Hall of Fame.

As a teenager, Jeffra, who stood five-foot-four, was a two-sport standout. He was so good on the links that he considered pursuing a career as a professional golfer. After retiring, he won several amateur tournaments.

In retirement, Harry Jeffra became very involved in local charities including the Baltimore branch of the Veteran Boxers Association. He developed an amusing schtick and was in demand as a public speaker on the rubber chicken circuit. With the money that he saved he was able to send all four of his children off to college.

For years after he quit he ring, Harry Jeffra had a large presence in his hometown. But he eventually faded from view. His name stopped bobbing up in the papers when Baltimore became a major league sports town. Major league baseball returned to Baltimore in 1953 when the St. Louis Browns moved here, taking the name of the city’s Triple-A franchise, the Orioles. That same year, Baltimore acquired an NFL franchise, the Colts. Professional boxing, so vibrant in Jeffra’s heyday with club shows every week, virtually ceased and the old-time boxers spawned by the city, even the best of them, became more obscure with each passing year. When Jeffra died in September of 1988 after a lingering illness, it took several weeks for the news to hit the papers.

Ah, but there was a time when the erstwhile Pimlico Kid was the toast of the town.

Gervonta

At age 24, Gervonta Davis is the youngest active American-born champion. Undefeated, he has stopped 20 of his 21 former opponents including the last 12. His life growing up in Baltimore was quite different from that of Harry Jeffra. There was no golf for him.

“As a tiny kid,” writes Corey McLaughlin in Baltimore magazine, “Davis often slept on the floor of his drug addicted parents’ house in possibly the roughest neighborhood in Baltimore City before going into foster care.” Nowadays, he can laugh about smashing up his $170,000 Ferrari in the first week that he owned it.

This past Wednesday, Davis was given the keys to the city of Baltimore by Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young in a ceremony at City Hall. In a city plagued by gang violence, the heavily tattooed boxer is being extolled as a role model, notwithstanding the fact that he has had several brushes with the law.

With the honor comes a responsibility, an obligation to give something back to his community. Harry Jeffra understood this. Now it’s Gervonta’s turn.

Gervonta photo by Amanda Westcott compliments of Showtime

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds