Featured Articles

50 Years Ago This Month, Rocky Marciano KOed Muhammad Ali

At the dawn of the year 1970, Rocky Marciano had been dead for five months and 1012 days had elapsed since Muhammad Ali had last stepped into the ring. But before the first calendar month was over, Marciano and Ali would sling leather in a battle witnessed by roughly a million people in theaters and arenas across North America and by millions more on TV in England and Japan.

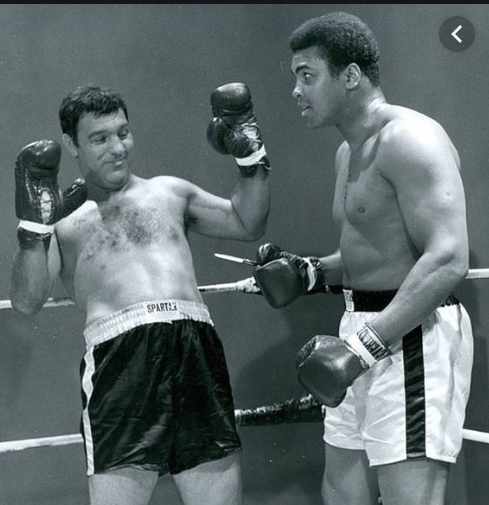

What they witnessed, of course, was a simulation, a faux fight. But it wasn’t as if Marciano and Ali were animated figures. They actually did share the ring, pulling their punches and occasionally landing a real punch by accident, over the course of 75 one-minute rounds filmed against a black backdrop behind locked doors at Chris Dundee’s Fifth Street Gym in Miami. Dundee, the older brother of the famous trainer Angelo Dundee, served as the third man in the ring.

The “fight” between the 45-year-old Marciano (49-0, 43 KOs) and the 28-year-old Ali (29-0, 23 KOs) was the brainchild of Murry Woroner. A man in his mid-40s who grew up in the Bronx, Woroner entered the radio field at a station in the coal-mining town of Harlan, Kentucky, and made several other stops before turning up in Miami where he started his own production company.

Three years earlier, the resourceful Woroner had concocted a heavyweight tournament consisting of 15 fantasy fights that he sold to 380 radio stations around the world. There were 16 entrants, seven deceased, and the last man standing became the mythical greatest heavyweight champion of all time.

A large panel of boxing historians rated each fighter on a host of variables, the results were coded onto punch cards that were fed into a bulky contraption called a computer, and the computer determined the winner of each match. (In the finals, Marciano rallied to stop Jack Dempsey in the 13th round.)

Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, was the only active fighter in the tournament. He was eliminated by turn-of-century stalwart James J. Jeffries in the second round.

Ali/Clay was so incensed by the verdict that he sued Woroner for defamation of character. Jack Johnson had run circles around Jeffries when Jeffries came out of retirement in 1910, and in Ali’s eyes it was absurd to think that he wouldn’t have conquered Jeffries in a similarly one-sided fashion.

Murry Woroner reportedly gave Ali $10,000 to drop the suit with the proviso that Ali film a simulated match with Marciano if Marciano could be lured out of retirement. Exiled from boxing and with his bankroll slowly dwindling, Ali accepted the offer. He received an unspecified guarantee plus a percentage of the profits.

In the late spring of 1969, when Marciano consented to participate, he had been out of the ring for 13 years. In retirement, his legend grew his larger – he was the only former heavyweight champion to retire undefeated – and so also did his waistline. A proud man, he lost 50 pounds before the first fake punch was thrown.

Marciano was a bleeder. A lot of ketchup was used during the filming, but lore has it that during one segment Marciano was cut between the eyes so severely that it necessitated a three-week recess. But Ali wasn’t unscathed either. He was sidelined, however briefly, when the lumps in his arms became too tender — or so it was written.

After the footage was edited and boiled down to a manageable length, it was placed in a vault where it was guarded, said Time magazine, more closely than the gold in Fort Knox. Only a handful of people knew how the “fight” would turn out and they were sworn to secrecy. Couriers delivered the final cut to exhibitors less than an hour before it was to be shown, an added measure of protection.

This was a first-class production. Every living former heavyweight champion – except Gene Tunney, who declined to participate – and other ring notables such as The Ring magazine founder Nat Fleischer, was interviewed and appeared on camera. Veteran New York sportscaster Guy LeBow, who had narrated the radio tournament, returned as the blow-by-blow guy.

LeBow wasn’t as well-known to boxing fans as Don Dunphy, but he was the perfect choice because of his familiarity with recreations. He had previously worked for the New York Giants baseball team whose road games (and all games in 1958, their first season in San Francisco) aired on a New York radio station with the announcer sitting in a studio working off a Western Union ticker.

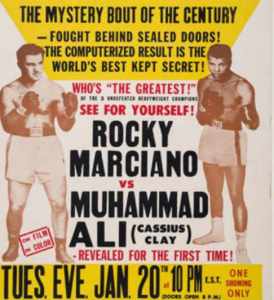

Marciano vs. Ali ran on Jan. 20, 1970, a Tuesday, with the opening credits appearing at 7:30 PM Pacific time; three hours later, to the very minute, in the East. At a few of the venues, the movie was conjoined with other entertainment. At Boston Garden, it was paired with a six-fight card. The ending of the fight, which saw Marciano win by stoppage at the 57-second mark of round 13, met with the roaring approval of the Beantown crowd, especially the Italians in the audience who venerated Marciano as if he were the Pope.

Ali, who watched the movie at a theater in Philadelphia, was foiled once again, and once again by a dead man. Three weeks after the final day of filming at the Main Street Gym, and not quite five months before the film appeared on the big screen, Marciano died when the small airplane in which he was an occupant, crashed in an Iowa cornfield.

Of course, Ali held no grudge against Marciano. The two reportedly came to like and respect each other during the course of their Miami adventure. Ali’s beef was with the computer which he characterized as a Mississippi redneck.

Seven different endings were filmed. It’s widely assumed that the version shown on TV in England was different than the version shown in the United States. That’s partly true.

Rocky Marciano wasn’t as venerated in England as he was in his native country. Conversely, Muhammad Ali was a far less controversial personality. A much smaller percentage of the British population were inclined to root against him.

When the fantasy fight aired in England, there was a great outcry that Ali had gotten a raw deal. To appease their viewers, a different version was acquired by the TV network. The revision, which aired three days after the original broadcast, showed Ali winning the fight on cuts. However, the round in which the fight was halted wasn’t perfectly clear.

Theater owners were forbidden to show the film more than once. If you missed it, you missed it, but eventually a surviving print was located and turned into a DVD. Released in 2005, it was re-titled “The Superfight: Marciano vs. Ali.” The posters for the original included both names under which Ali was known, but the words “Cassius Clay” were dropped from the promotional materials for the DVD.

Murry Woroner’s fantasy fight hardly settled the argument as to who would have won if Ali and Marciano had met in their respective primes. Many that favor Ali believe he would have won in a cakewalk (similar to Jack Johnson over the aforementioned Jeffries), whereas those favoring Marciano invariably see him taking a lot of punishment before he wears down Ali with his relentless pressure (similar to the first Ali-Frazier fight with Marciano assuming the role of Joe Frazier).

Where do you stand?

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers