Featured Articles

Remembering ‘Skeeter’ McClure: Olympian, Middleweight Contender, Psychotherapist

Remembering ‘Skeeter’ McClure: Olympian, Middleweight Contender, Psychotherapist

“He was as good a fighter then as Sugar Ray Leonard was later,” said the legendary Madison Square Garden matchmaker Teddy Brenner in 1984. “If he’d been brought along slowly, he could have done everything Leonard did.”

Brenner was referencing Wilbert “Skeeter” McClure. Considering that McClure ended his pro career with a record of 24-8-1, it would appear that Brenner was exaggerating, but McClure’s pro record was a poor barometer of his career accomplishments and when it came to evaluating talent, no one had a more respected opinion than Teddy Brenner. Also, as his post-boxing life would show, McClure was a man cut from a very fine cloth.

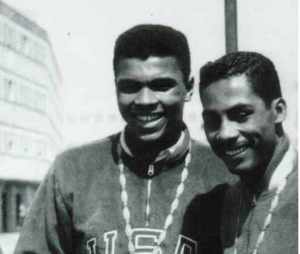

Born and raised in Toledo, Ohio, the son of a farmer turned sewing machine repairman who was an avid reader, Skeeter McClure was the dominant amateur junior middleweight in the world between 1958 and 1960, winning two national AAU titles and an Olympic gold medal. He was one of three members of the U.S. boxing team to win gold at the 1960 Games in Rome, joining Eddie Crook, a 31-year-old Army sergeant, and an 18-year-old phenom from Louisville named Cassius Clay.

In Rome, McClure was matched against local fan favorite Carmelo Bossi in the finals of the 156-pound competition. He was clearly trailing after two frames, but mustered a big rally in the third and final round to pull the fight out of the fire.

McClure would recall that he almost turned down a spot in the Olympics as it meant that he wouldn’t be able to work and save up money that summer for his next semester of college at the University of Toledo where he was on course to graduate with a degree in English. Recognizing the publicity value of having an Olympian in their midst, the school stepped up and waived his tuition.

The 1960 Olympics were the first Summer Games to be telecast in North America and for that reason are often considered the first modern Olympics. But not every event was televised. McClure’s family didn’t learn that he had won the gold medal until the next day when they heard it on the radio. “Ours was the last of the innocent Olympics,” said McClure in 1998. “Athletes weren’t taking steroids or being chased by shoe companies. Nowadays, the money pressure is so big, the spirit of the Olympics has become corroded.”

McClure made his debut as a Madison Square Garden headliner on Aug. 4, 1962. In the opposite corner was Farid Salim, the middleweight champion of Argentina. McClure only had nine fights under his belt. Salim was a 12/5 favorite.

Skeeter out-classed him. “(McClure) beat his taller and more experienced opponent with crisp left jabs, repeated left hooks, and lightning-fast combinations to the head as he circled constantly away,” said the UPI correspondent. A return visit to Madison Square Garden, where he won a unanimous decision over Bahamian veteran Gomeo Brennan, prefaced his crossroads fight at the Garden with Luis Rodriguez.

McClure was 14-0 heading into the nationally televised fight, but he was in too deep against the Angelo Dundee-trained Rodriguez who was 52-3, with all three losses by split decision, two to future Hall of Famer Emile Griffith, a man he would subsequently defeat.

The fight was close, but McClure lost a unanimous decision. They met again 10 weeks later in Rodriguez’s adopted hometown of Miami Beach with the same result, only this time the Cuba-born Rodriguez won by a wider margin. McClure was 10-6-1 from that point on, the draw coming in a rematch with Rubin “Hurricane” Carter who was awarded a split decision over McClure in their first meeting. He retired after being stopped in the 10th-round by teak-tough Billy “Dynamite” Douglas, the father of James “Buster” Douglas.

After his fourth pro fight, McClure was drafted into the Army. That impacted his training, but was fortuitous as it enabled him to continue his education under the GI Bill. He eventually earned a PhD in psychology from Detroit’s Wayne State University which led to a job teaching at Boston’s Northeastern University where his specialty was group therapy. He purchased a condo in Chestnut Hill and settled into the life of an academician with his ever-present pipe and (presumably) tweed sports jacket with leather elbow patches. (After he quit teaching, he had a private practice, taught seminars for industrial clients, and was a consultant to the Brookline (MA) Police Department on police/community relations.)

In 1993, McClure was appointed to the Massachusetts Athletic Commission, rising to the post of chairman. During his tenure he initiated several reforms including mandatory AIDS testing. But he resigned after only five years after butting heads with newly appointed state boxing commissioner Mark DeLuca. He thought it inappropriate that DeLuca allowed his two children to sit ringside in seats reserved for boxing officials and did not hold back his feelings.

Looking back on his pro career, McClure said, “If anybody wanted a textbook case of how to take a good fighter and ruin him, I was it.” No doubt it grated on him that Carmelo Bossi, who had only four pro fights outside Europe, losing all four, was navigated into a world title shot and emerged with the title.

But McClure was never bitter, at least not outwardly. In fact, he had only good things to say about the sport which taught him important life lessons and opened doors that enabled him to achieve goals that he likely would not have achieved otherwise. “When I look back on my career,” he told the late Dick Schaap, “I don’t remember beating up on guys, I remember out-thinking them.”

After leaving the commission, McClure supported boxing in other ways. He was an active member of RING 4, the New England branch of the Retired Boxers’ Association. Longtime boxing scribe Ted Sares, a member of the organization’s Hall of Fame, would write that much of what he learned about the history of boxing was learned talking with McClure at RING 4 luncheons.

During the last decades of his life, when journalists sought out Wilbert McClure they always veered the conversation into McClure’s recollections of his famous amateur teammate. “Even then,” he told Thomas Hauser, “you knew (Muhammad Ali) was special; a nice, bright, warm, wonderful person.” In a widely syndicated newspaper story by the aforementioned Schaap, McClure said, “I think Ali was as great as he said he was. He had a destiny that would not be swerved.”

Wilbert McClure, who had health problems the last few years of his life, died last week (August 6) at age 81. “Skeeter” never achieved anywhere near the level of fame that would envelop Muhammad Ali, but he was a great boxer and an even greater person.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers