Featured Articles

60 Years Ago This Week, Cassius Clay Brightens Up The Eternal City

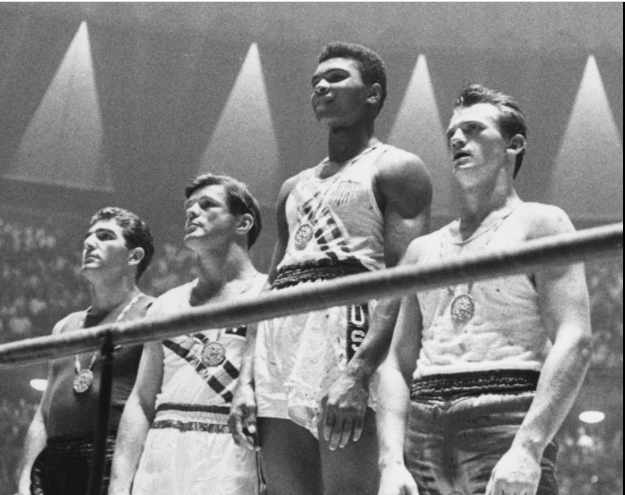

On Aug. 17, 1960, the first of five planeloads of U.S. Olympians arrived in Rome. The boxers came with the first wave because boxing would be first on the “bout sheet,” beginning right after the opening ceremonies on Aug. 25. Three members of that team would win gold medals including the heavily touted Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., an 18-year-old light heavyweight from Louisville.

Amateur boxers got a lot more exposure back in those days. The previous year, Clay’s bout with Tony Madigan was televised nationally on ABC along with two other bouts from Chicago Stadium. The occasion was the annual Chicago/New York Inter-City Golden Gloves meet matching the top amateurs from the East and West.

Tony Madigan was a two-time Olympian for Australia. He had taken up residence in Rye, New York, a bedroom community of New York City, for the purpose of honing his game under the schooling of Cus D’Amato who had guided 17-year-old Floyd Patterson to a gold medal in the 1952 Games in Helsinki. With all that experience, it wasn’t surprising that Madigan outclassed the field in his weight division in the New York tournament.

Tony Madigan was 29 years old. Cassius Clay was 17. It was boy against man in Chicago and the boy won. Madigan pressed the action, but Clay’s “pointed combinations” prevailed.

Clay won several more tournaments after that, most notably the 1960 Olympic Trials in San Francisco. He almost didn’t go because he had a phobia of flying.

The stars of the 1960 U.S. Olympic team were flag-bearer Rafer Johnson who set an Olympic record in the decathlon, sprinter Wilma Rudolph who took home three gold medals and was proclaimed the fastest woman in the world, and a basketball team starring Oscar Robertson and Jerry Lucas that clobbered their eight opponents by an average of 42.4 points per game.

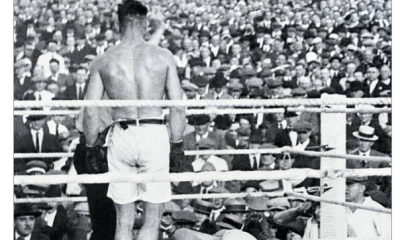

And, of course, the kid from Louisville who knocked off old foe Tony Madigan in the semi-finals and then on Sept. 5 conquered a Polish southpaw with an impossibly long name to capture the gold. But the kid wasn’t celebrated for only what he accomplished in the ring.

If I may digress for a moment, Dr. Robert Voy, who runs a sports medicine clinic in Las Vegas (and still practices at age 87) has worked with numerous Olympians over the years, both Summer and Winter. Voy, who was the Chief Medical Officer of the U.S. Olympic Committee from 1984-89, once told this reporter that of all the athletes, he most enjoyed working with the boxers because they were the most unspoiled. There were no prima donnas in their ranks; that came later after they turned pro and were exposed to all the venal characters that inhabit the sport at the professional level.

Dr. Voy wasn’t in Rome in 1960; that was a little before his time. But if he had been there, he would have had a very pleasant time interacting with the unspoiled kid from Louisville.

In Rome, the Eternal City, Cassius Clay was the unofficial Mayor of Olympic Village. He was dubbed as such because of his outgoing personality. “Cassius Marcellus Clay is a delightful, refreshing, naïve extrovert,” wrote Sid Ziff, on assignment for the Los Angeles Mirror. “Completely without inhibitions, he even made friends instantly with the Russians. He stopped a party of them marching to their quarters, refused to be rebuffed and soon had his picture being taken with their arms around him, everyone wearing ear-to-ear smiles.”

Let’s put this into context. In the year 1960, relationships between the U.S. and Russia were especially tense. We were in the midst of the Cold War. On the very same week that the U.S. boxing team arrived in Rome, CIA pilot Francis Gary Powers was convicted of espionage in a Russian court after his U-2 plane was shot down on a reconnaissance mission. Air raid drills in American public schools hadn’t yet run their course. The possibility of a nuclear confrontation between the two superpowers seemed very real.

If Americans weren’t conditioned to despise the Russians (the “lousy Commies”), they were at least conditioned to be wary of them. And the Russians undoubtedly felt the same way toward us. But no one told the kid from Louisville.

The purpose of the Olympic Games, at least in theory, is to build a more peaceful world through “mutual understanding with a spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play.” In the Olympic Village of Rome in 1960, no one better embodied the Olympic spirit than Cassius Clay. “We’d walk around and he’d go up to (strangers) and shake their hands,” recollected his teammate Wilbert “Skeeter” McClure. He seldom went anywhere without his camera. He was building a scrapbook to show the folks back home.

Back home in Louisville, he received a royal welcome. He was feted at a ceremony at Central High School, his alma mater. “When we consider all the efforts that are being made to undermine the prestige of America, we can be grateful we had such a fine ambassador as Cassius to send over to Italy,” said Atwood Wilson, the school’s Principal. “If all young people could handle themselves as well as he does, we wouldn’t have any juvenile problems,” added Louisville Mayor Bruce Hobitzell. “He’s a swell kid.”

Cassius was named after his father. There were other Cassius Marcellus Clay’s in Louisville as the boxer was growing up there, including a prominent State Senator. The others were white folks, descendants of the original Cassius Marcellus Clay, a fiery abolitionist who among other things donated the land for Berea College, the first racially integrated college in the South when it opened in 1855.

Cassius liked his name back then, he thought it had a nice ring to it, but as we know he would eventually abandon it. Under his new name, Muhammad Ali, he became a polarizing figure, a man beloved by millions around the world but yet loathed by many of his countrymen. He was a shoo-in for Fighter of the Year in 1966 after making five successful heavyweight title defenses, but The Ring magazine, the sport’s self-proclaimed Bible, refused to recognize him and left the laurel vacant. “Most emphatically,” wrote Nat Fleischer, the magazine’s founder and editor, “(Ali) could not be held up as an example to the youngsters in the United States.”

Over time, Fleischer’s opinion got turned on its head. Ali came to be seen as a positive role model, a “tireless humanitarian and philanthropist” in the words of the press release announcing that he had been selected to receive the prestigious Liberty Award, an honor that came his way in 2012. Last year, three years after his death, Louisville honored him by naming the city’s airport after him.

Muhammad Ali, the former Cassius Clay, the “swell kid” from Louisville, would go on to become the most famous person on the planet. At the height of his fame, it was said of him that if he dropped out of the sky and landed on a remote island where there was no television, no newspapers or magazines, the natives would still recognize him. And his first step in becoming a global superstar came 60 years ago this week in Rome, the Eternal City.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More