Featured Articles

Every Joe Gans Lightweight Title Fight: Part 1; Frank Erne 1

Joe Gans of Baltimore lost the confidence and respect of the sporting public last night by deliberately quitting in the twelfth round of the bout with Frank Erne at the Broadway Athletic club. He had an excellent chance of becoming lightweight champion. He will now be looked upon as the champion quitter. – The New York Evening World, March 24th, 1900.

Eleven years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Joe Gans was born. His was a world in which the enslaved were reborn as fourth-class citizens into a country reeling from war. The average African- American could expect to live thirty-three years; the average white American, forty-seven.

Joe Gans scratched out more years on this earth than the average African American, but barely. In thirty-five years, thirty-five years marked with violence and dash, he made a mark so indelible upon the fistic universe that it continues to echo down the ages. Even among the early black boxing champions, men who had to battle a hostile power-structure in addition to lethal boxers fighting in the toughest conditions, men like George Dixon, Joe Walcott, and Jack Johnson, he is a giant. I could not name ten fighters who achieved more.

And yet, as the 1900s dawned, he made himself a pariah. Gans engaged in conduct regarded as outrageous and career-threatening at a time when much more moderate sporting offences could cause a black contender to be excluded for years. He fought two fights in 1900 which would have rendered a lesser man a footnote, one of which was so notorious as to remain infamous even today.

The other was his first fight for the lightweight title.

In this series, we will tell the story of each one of the title fights Joe Gans fought during his lightweight career which is the same as telling the story of the sport’s greatest division in the first decade of the century. Gans towered over the most stacked lightweight division ever assembled for most of those years.

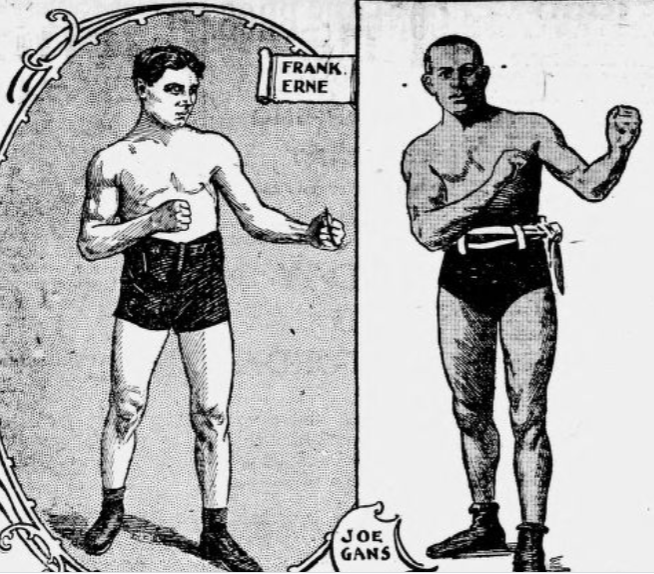

But in 1900, the champion was Frank Erne.

“Erne is conceded to be one of the brainiest, fastest, cleverest boxers in the ring to-day,” reported The Brooklyn Daily Eagle in previewing the fight. “He has a long and successful career in the ring and won his title of champion by defeating Kid Lavigne in a memorable battle.”

Lavigne himself was one of four men from this deepest lightweight era to hold an argument for placement among the twenty greatest lightweights in history; Erne had “battered his opponent out of the title” while “never once losing his cool.” It was a masterful performance from a speedy, clever, self-possessed fighter, probably one of the ring’s great jackals.

Gans though, was different. Lavigne was diminutive and sought out an equalising punch against superior boxers, but Gans backed his generalship and skill against any and every opponent he had or would ever meet. This would include Erne.

Still, one newspaper named Erne “far more clever” but nevertheless noted that Gans was “a cool ring general” who “seems able to hit harder.” This last would prove an understatement – Gans would go on to stop at least a hundred men in the ring. His mission to stop Erne began at the Broadway Athletic Club, on March 23, 1900 over twenty-five rounds, both men having agreed to weigh in that afternoon at 133 pounds. At stake were fifty percent of the gross receipts.

The poundage was the problem; Gans was reportedly not a fan of the champion’s 133lb limit but what the Waterbury Evening Democrat called “a monster betting event” was something more certain to go ahead then than it is now. Joe Gans was installed as an early favourite.

As the boxing world turned its collective eyes towards the monolithic contest that was Jim Corbett’s defence of the heavyweight title against the surging James Jeffries, Gans and Erne began training. Erne moved from his base in Buffalo to Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn where his camp, as always, was run to the rigid discipline enforced by his own mother.

“I wanted a chance at Gans,” Erne told reporters,” and now there is nothing to do but prepare myself in the physical way. I expect to enter the ring weighing 132lbs, and although Gans may be a little heavier, I think I will be heavy enough to win out…I like to box these clever fellows.”

The excellence of his condition was noted but the betting line refused to budge and as the fight came closer, sporting men in search of money for Gans complaining bitterly of prices available to them.

“It is generally admitted that Erne is the cleverest boxer in the business,” reported The St. Paul Globe. “Those who have watched him train for the coming fight declare he has developed the ability to punch hard. This will be good news to a host of admirers who have been slow to back him.”

Slow with reason. The picture of Gans that begins to emerge is formidable. Swift, confident and above all economical, he is repeatedly referred to in the build-up as the favourite and the thousands being wagered upon him are revealed in eye-watering detail. A man named Al Smith took it upon himself to wager a thousand dollars on Gans, around thirty thousand today; others were only slightly less forthcoming. The men making these wagers were “sporting men”, the fuel that drove championship boxing. This was the weight of responsibility that Gans nonchalantly wore when stepping into that Broadway ring.

“Never before,” wrote The Brooklyn Eagle of the fight, “have two so clever lightweights met in the roped arena. Erne, the holder of the championship was never in better condition. The muscles showed under his pink skin like living steel, and there was a dangerous glint in his eye.”

Gans, for his part, “was the more symmetrically built and looked the heavier of the two” and wore “an expression of supreme confidence.” Betting at ringside continued apace, always with those betting upon Gans receiving the rougher edge while a bizarre argument about the judges erupted in the ring. Neither man appeared perturbed. When the bell for the first rang, Erne charged Gans.

But let us be clear: there is charging and then there is charging. Erne was a counterpuncher and determined to press the pace, draw the lead and punish mistakes. Gans declined. This led to “considerable sparring” according to The New York Tribune, with “only a few blows struck.” Gans, having successfully forced Erne to lead, a huge concession, blocked with genius, though Erne’s own defences were also noted.

In the fourth, Gans began to take control, to the displeasure of the packed crowd which showed a preference “for Erne, perceptibly, probably on account of his color” according to The New York Herald. In the fifth, Erne challenged Gans for ring centre and the fight broke out in earnest. First, they traded lefts, Erne then sought out the body while Gans rattled two-handed shots off Erne’s face; a short brawl broke out; Gans dominated, then they clinched, Erne emerged and “tried for a knockout with his right” a punch taken nonchalantly on the shoulder by Gans according to The New York Morning Telegraph. The New York Evening World, which put Joe’s apparent slow start down to nerves, saw him now in control of the fight.

Erne’s second was the fistic genius Kid McCoy, a ring general of note in his absolute prime coming off back-to-back wins over Peter Maher and Joe Choynski. Between rounds McCoy offered Erne stark advice that may have been crucial: that it was “useless” trying to outhit Gans to the head and that he should turn his focus to the body. “When the bell rang for the beginning of the sixth,” continued the World, “Erne came out of his corner…and immediately started in to obey [McCoy’s] instructions.”

The round nevertheless belonged to Gans. He countered Erne’s left-hand viciously, although “Erne surprised everybody by replying with similar blows,” by some reports, landing a vicious right hand to the neck close to bell that rattled Gans. It was Erne who emerged from the round bleeding though, his face smeared, while Gans wore not a mark. Erne’s new problem was more serious than a little blood however: his straight punches were now being countered by the Gans hook.

In a twelve-round fight, we are able as fight fans to pick out key rounds. As a rule of thumb if one fighter should dominate for three consecutive rounds, we know the next round to be key. A twenty-five round fight is different. A fighter can lose ten consecutive rounds and still win clearly on points. Still, this left-handed crisis made Erne’s situation acute and the seventh seemed a round of meaning.

This was reflected in its violence.

According to The Sun, Erne rushed Gans “like a tiger” but Gans “used his feet skilfully whenever Erne attacked him and yet always had heavy counters ready.” It was his right hand that did the damage here, dashing blood from Erne’s face and to the canvas while Erne countered with the left to the body and a single right hand to the head. Towards the round’s end they swapped hard punches, Gans taking control, Erne fighting back, Gans “on the defensive” at bell.

Erne’s solution to the left-handed problem seems to be one of aggression, accepting the role of pressure-fighter and augmenting his assault by the total number of bodypunches he threw, which were many. Gans continued to joust with great skill, deflecting headshots with the same consummate ease as throughout but the bodypunches were troubling him. Erne’s shots to the gut made him vulnerable to the Gans right but also opened up right-handed opportunities of his own; at the beginning of the eighth, Erne played for the stomach with his left but was able to dash shots to the nose, too. Gans seemed to find a new level for his own boxing, whipping a right hand to the mouth, first drawing Erne’s guard up with a left-handed feint to the temple. The Gans right “was doing considerable execution for he did nearly all of his punching with it” – what had begun a left-handed contest won by Gans had become an exchange of lefts (mainly to the body) for rights (mainly to the head).

But the eighth was a round Erne may have won, stopping the rot that had begun in the fourth, although many sources have it even; either way, Erne was now back in the fight with both the seventh and the eighth unclear where Gans had been dominating. In the ninth, Erne found another gear, but was never more committed to his left-handed attack to the body; Gans landed a crackling right-hand to the mouth which brought on terrible fighting. “For a full minute,” wrote The Eagle, “both men dropped science and slugged with both hands.” Erne took the honours in this brutal shootout: “At this game Erne showed that he was dangerous,” commented The Sun, “and the Baltimore man knew it.”

Applauded back to his corner at the end of the round, Erne emerged for the tenth with the utmost aggression and the truth of it is a question of the eye of the beholder. For some onlookers, Erne was “rushing Gans around the ring” while doing meaningful bodywork; The Eagle took a different view, seeing Gans as the matador, he “side-stepped and Frank almost shot through the ropes. Several times Erne rushed but Gans met him with short lefts to the face.”

Such is the genius of Gans that he has reduced Erne to a bull; such is the brilliance of Erne that he could become one and remain competitive with Gans.

The eleventh was bedlam; Gans consistently timed Erne with his left hand at range so Erne was forced to rush once more, there was simply no other way for him to work. Inside, and during exchanges as Gans reclaimed distance, the fighting was close and hotly contested and would favour the man who could exert himself the least to sustain the balance. That man, probably, was Gans, but Erne by now was fully committed.

So, at the opening of the twelfth round, Erne rushed once more. Remember the right-hand Erne threw earlier in the fight that Gans took casually on the shoulder? Here, I believe, was another such punch, but this time it found its home. Gans doubled up immediately and moved towards Erne’s corner, Erne in hot pursuit. The best description of what followed is likely from the Evening World:

“Gans tried to run away and Erne, forcing him against the ropes, dealt him a fearful right-hand swing over the heart. As he did so, Gans swung his right and there was a collision, Erne’s head cutting a big gash over Gans’s eye.”

Gans pawed at his eye, and then dropped his gloves. Referee Charley White pressed in to hear him:

“I’m blind. I can’t see any more.”

Gans turned his back and walked to his corner. White took the only option available to him and raised the hand of Frank Erne. The champion had successfully defended his title.

“Blood streamed copiously from a cut,” reported the same paper, but this was a disaster for Gans. He was “denounced in the strongest possible terms” by the gambling men ringside. Gans “quit like a steer” to the “thorough disgust” of those in attendance according to The St. Louis Republic. The Sun spoke to many who were “loud in their expressions of opinion that the colored boxer simply quit when he saw that he was overmatched, declining to subject himself to additional punishment in a contest which he was satisfied was a losing one.”

As to whether this was the case, it seems unlikely given what we know of Joe Gans. Already he had seen out twenty-five rounds several times, including against the teak-tough Elbows McFadden. More, most newspaper reports give Gans the edge at the time of the stoppage, not Erne, and although the fight was in the balance during that fateful twelfth round there was no reason to believe Erne would have emerged with the advantage; in fact, the opposite seems more likely.

Still, it was unusual in this era for a fighter to quit with a cut. Nearly a decade later, Stanley Ketchel and Billy Papke would beat one another into blindness in back-to-back fights rather than risk the stigma associated with quitting. Even today it can be difficult for a fighter to bounce back from a perceived quit job; in 1900 such matters were even more acute for a fighter. Gans was labelled with the dreaded “yellow streak”, the white feather. He defended himself as robustly as was possible.

“The blow that cost me the fight with Frank Erne was delivered with his head,” he told The World. “I do not blame him for it. We were both fighting close in at the time. We both swung at the same time and ducked. Our heads came together with a crash. The blow was an awful one. Immediately the blood poured from the cut and run into my left eye. I was blinded. I could not see Erne. Knowing that I would be knocked out, I told Charley White that I could not see Erne and would have to give up. Up to the time I received the blow on the head I had things my own way. I was taking things easily and waiting till I could knock Erne out. I had his face in a bad way. I could always reach him with my right. All I ask is a return match. I think the next time we meet I will whip him easily.”

Erne feared no man but was not of a mind to provide the dangerous Gans a rematch quickly with his stock so low. Instead, he elected to drop down in weight for a legitimate superfight with a new and emerging superstar named Terry McGovern.

Gans, too, stalked McGovern. This was a money fight against a smaller man and although McGovern had proved himself a terrific puncher – including against Erne, who he dispatched in three – Gans was not about to turn it down. A six round contest was staged in Chicago, in which McGovern only had to last the distance to take the winner’s end of the purse. Instead, he blasted Gans out in two.

Gans was ridiculed and pilloried for engaging in the lowest form of subterfuge, a fake fight, culminating in the misery of a falsified knockout. “He never attempted to mix it up,” said The Daily Morning Journal of Gans, “he never made an effort to use his counter left for which he is so famous…he was rolled down on the floor time and again after every rush McGovern made.” Chicago banned boxing for a quarter of a century in the wake of what remains perhaps the single greatest debacle in boxing history.

It was Christmas of 1900. The dawning of the year saw Joe Gans rated one of the most prominent fistic stars in America but as he carved the turkey, he was three things, two of them new: a cheat, a quitter, and an African American. Any one of these things might have been enough to keep Gans from a championship ring.

But by the summer of 1902, Joe Gans would reign as the lightweight champion of the world.

(AUTHOR’S NOTE: This series was written with the support of Joe Gans expert Sergei Yurchenko. His work can be found here.)

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More