Featured Articles

Checking In With Christian Giudice, Author of Four Biographies of Latin Ring Greats

Taking on the task of documenting the lives of Roberto Duran, Alexis Arguello, Wilfredo Gomez and Hector Camacho in book form was daunting, but Christian Giudice, like those four world champions, rose to the challenge.

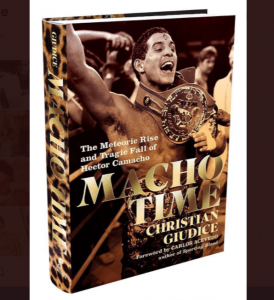

The books in question are “Hands Of Stone: The Life And Legend Of Roberto Duran,” “Beloved Warrior: The Rise And Fall Of Alexis Arguello,” “A Fire Burns Within: The Miraculous Journey Of Wilfredo ‘Bazooka’ Gomez,” and his most recent work, “Macho Time: The Meteoric Rise And Tragic Fall Of Hector Camacho,” released last year by Hamilcar.

All had storied ring careers and all are enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

“I loved the way I felt and how I was treated in each of those countries. I gained lifelong friendships in Panama, Nicaragua, and Puerto Rico,” Giudice said of his time doing research on those four legends. “Although it has been a while since I have traveled, I really enjoyed my time meeting new people each day in and outside the boxing spectrum. There is something different about Hispanic boxers that has attracted me to write about them over the years.”

Giudice tried to pinpoint why he is drawn to Latino boxers. “I don’t know if I can explain it. To me, each fighter I wrote about had to overcome a fierce struggle and then immediately face the pressure of placing a country on his back,” he said. “Thus, each fighter has encountered magnificent highs and excruciating lows and must find ways to handle the positives and negatives publicly. I see that conflict emerge and when I write about that fighter, I have to be able to convey how the fighter is able to handle fame and what comes with it.”

Giudice added: “Ever since I traveled to Panama to write a book on Roberto Duran, I knew I wanted to always write about Latin fighters,” he explained. “It was my way of giving back to the people of Panama who treated me like family. It also gave me an opportunity to travel. I wanted to cover Latin fighters who were not only fabulous boxers and heroes in their countries, but also lived lives that transcend the ring.”

Each boxer was unique and their stories needed to be chronicled. “I don’t think too many fighters experienced the same rise and fall of a Duran or the turbulent lifestyle of a Hector Camacho or the political upheaval of Alexis Arguello,” said Giudice, who grew up in Haddonfield, New Jersey and teaches English at Harper Middle College High in Charlotte, North Carolina. “Voted the greatest Puerto Rican fighter ever, Wilfredo Gomez lived an amazing life as an icon in Puerto Rico. Ironically, the pressure on Gomez as a Puerto Rican icon intensified once his career ended. Each one of those fighters had a story that needed to be told. I am very fortunate to have had the opportunity to do so.”

Duran, who rose from slum to arguably the finest lightweight ever, was sometimes painted by some in the media as being something of a bully.

Giudice’s encounters with Duran, who from 1968 until 2001 posted a ring record of 103-16 with 70 knockouts, often proved enlightening.

“I learned a lot about his family life, since I traveled back to his family’s hometown in Guarare, Panama. I learned a lot about the in-depth details of family stories that helped shape who Duran really was,” he said. “Stories like how he was caught stealing fruit out of the trees off the estate of landowner [later manager] Carlos Eleta and how he used to tell jokes to his grandmother as a young boy. I listened to these stories, which were told through the lens of family members. He wasn’t the brash, intimidating guy that everyone made him out to be. He certainly didn’t embrace those labels, and, as I was writing the book, those childhood stories humanized him.”

Where does Giudice, who has an English degree from Villanova and a master’s degree in journalism from Temple, place Duran among lightweights?

“I rank Duran as the best lightweight of all time. I don’t consider it close. At his finest, he was unbeatable,” he said. “And his best weight was 135 pounds. People often come up with other great lightweights from different eras, but Duran was so skilled and, well, perfect at that weight class, it is difficult to imagine another fighter at the same level.”

In his prime, Duran was a force of nature. “With the exception of his victories over Esteban De Jesus, I still consider his first fight with Sugar Ray Leonard [at 147 pounds] his best performance. He brutalized Ken Buchanan for his first title, but the way he prepared for Leonard was unlike any other fight,” Giudice said. “He wanted it so bad. Truth is, Duran shocked Leonard before the bout and then went in the fight and fought with the same intensity. Everything he promised, he backed up. Because there was no pretense, Duran became the fan favorite as soon as he arrived in Montreal for the fight. What a performance. I believe he looked at it more than a fight, and then backed up everything he said he would do.”

That bout took place on June 20, 1980 at the Olympic Stadium and ended up a unanimous decision victory in favor of Duran.

Five months later at the New Orleans Superdome, Leonard earned redemption when late in the eighth round, Duran shockingly walked away and turned his back on Leonard and said something to Octavio Meyran, the referee.

Giudice addressed what happened. “When I traveled to Panama to write the book on Duran, I had the opportunity to meet his longtime manager and friend, Carlos Eleta. I was hesitant to speak about ‘No Mas’ fearing that it would be difficult for Duran and his family and friends to talk about it, but Eleta was very clear about one thing: In his mind, he needed to make the rematch immediately, rather than wait,” he said. “Financially it made sense, but physically many people felt that Duran needed time to rededicate himself back to the ring. Duran did not want to make that rematch so quickly, but Eleta said that at the rate Duran was going with his partying that he would never fight Leonard again.”

Of course, the fight was made and Duran became annoyed with Leonard, who moved, jabbed and landed numerous punches, and in the seventh round began taunting him, which frustrated him.

“He [Eleta] was also clear that Duran never said, ‘No Mas,’ but instead said, ‘I will not fight with this clown anymore.’ As the years went by, people concocted so many different stories, but most of them had little merit,” Giudice said.

In Nicaragua, Arguello, who capped his 27-year career with a mark of 77-8 and 62 kayos, was a near-mythic figure.

“The Nicaraguan people had never witnessed anything like Alexis. As he once said, he lived a life that no one else could have lived. He was kind, affectionate, devoted, and, most importantly, loyal,” Giudice said. “During a career that was plagued by politics, corruption, and the reality of having everything taken from him and being exiled from Managua, Arguello’s career was never just about wins and losses.”

Giudice continued: “His people recognized the injustices that he faced and loved him for the fact that he was fiercely devoted to Nicaragua until the end,” he said. “It was easy to see how beloved Alexis was, not only in Nicaragua, but here in the United States. He was genuine, and always treated others with respect and kindness. He was an original.”

Arguello committed suicide on July 1, 2009 at age 57, and is still regarded as a hero.

Camacho had a commanding aura in and out of the squared circle and his life also ended tragically. On November 24, 2012 at age 50, he was murdered.

“Hector had a presence that everyone felt. What was unique about Hector was that even when the spotlight was not on him, he felt an urgency to ensure that by the end of the event, everyone would be looking at him,” said Giudice of Camacho, who boxed from 1980 through 2010 and crafted a record of 79-6-3 with 38 knockouts. “Hector was a natural entertainer and understood that, in his mind, he had to test boundaries and create controversy even when it didn’t exist. Away from the spotlight, those who loved him, describe a much different, more humble person, but not when it came to boxing.”

With a mark of 44-3-1 and 42 kayos over 15 years, Gomez was simply sublime.

“Gomez was so good at 122 pounds, but I just think he started to fade too soon and his body of work doesn’t compare with Duran and Arguello because of longevity and other factors,” Giudice said.

There is something all four men have in common that made them worthy of having their stories told.

“When you look at these four fighters, all of them had to struggle to survive growing up and then use their boxing skills to get their families out of poverty,” Giudice noted. “That forced them to make sacrifices, grow up a lot quicker, take financial responsibility for their families, and then live with an added discipline.”

And they each had to perform at the highest level in the ring. “The pressure to live up to the expectations of being a champion must have been so difficult,” Giudice reasoned. “Thus, in their lives, for so many years, there was little room for error. Then once they reached that level of superstardom, they were not able to truly embrace it because they had to prepare for their next bout. Also, every mistake is magnified publicly, so the emotional ups and downs made it even harder. Nothing was ever ‘normal’ for them.”

Even for the best, being a boxer is a tough way to make a living and it’s often lonely once the ring lights dim.

“All fighters struggle with finding an outlet to replace the high that the sport provided them,” Giudice said. “Hector and Alexis were no different. The only difference was that Hector had succumbed to drugs and other vices his whole life; whereas, Alexis struggled with his mental health throughout his life and then was cornered in an untenable position by powerful people in Managua who manipulated him at the end of it.”

The end for many is more often than not extremely sad. “Only a handful of fighters have a backup plan once their careers end,” Giudice said. “Even those fighters cannot fill that empty space. It is not an empty space, but a huge gaping hole. For adoring fans, Hector and Alexis had given them so many thrills and wonderful moments that even the prospect of meeting them or a photo gave them a level of fulfillment or happiness.”

Giudice went on: “But for the fighters like Alexis and Hector, the high of being in the ring is something that stays with them forever. No standing ovation in retirement can bring those memories back, so they need to find other pursuits,” he said. “Alexis was aware of this; Hector was well aware of this, too, but, back then, there was not the support available to combat those pressures.”

Note: Christian Giudice’s books can be ordered from Amazon or direct from the publisher and are found at better booksellers everywhere.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More