Featured Articles

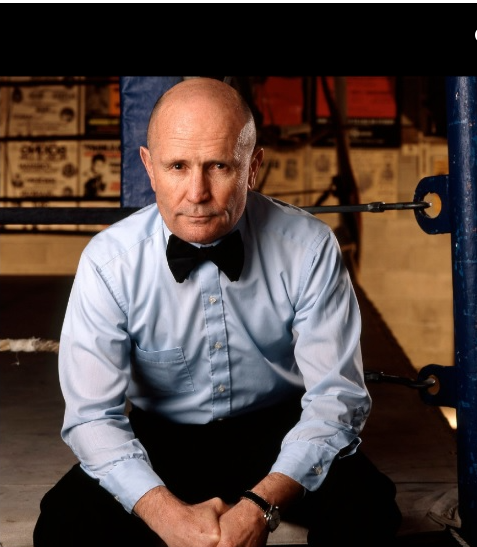

R.I.P. Hall of Fame Referee Mills Lane whose Life Story was Worthy of a Big Screen Biopic

He probably never should have lasted as long as he did. After famed boxing referee Mills Bee Lane III suffered a debilitating stroke in March 2002, which left him partially paralyzed and unable to speak, the consensus medical opinion was that he it would be touch-and-go for him to survive the first few weeks. Even when he did make it through that critical early stage of recovery, it seemed a medical certainty that the feisty former Marine, at 65, could expect no more than a life expectancy of five years, tops, and most likely as a virtual prisoner in his own body.

But Mills Lane had been the third man in the ring long enough to discern when certain fighters, well behind on the scorecards and unlikely to find a path to victory, had shown enough resolve and moxie to go the distance if possible and make it to the final bell. It is a disposition of proud defiance he admired in others, and had exhibited himself on numerous occasions as an unapologetic free spirit. On those occasions when one must choose to be a leader or a follower, the little guy with the bald head and raspy voice always chose to stride boldly to the front.

For 20 years Lane was unable to verbally communicate with the family he so dearly loved, but there are some things, including goodbye, that a father need not express in words to make his feelings known. And, so, Mills Lane, at 85, silently took his leave of a life that mostly had been well spent in the early morning hours of Tuesday, Dec. 6, with his wife, Kaye, and sons Terry and Tommy, and their wives, at his bedside in the patriarch’s adopted hometown of Reno, Nev.

“He was on hospice at home, in Reno, with the family around him when he passed away between 2 and 2:30 in the morning, but his time of death wasn’t officially recorded until 3:16,” older son Terry noted. “He had a rough couple of days. It all kind of came out of nowhere and things progressed quickly. My brother and I got back to Reno this past Thursday to be with my mother at Dad’s bedside. Monday was one of the worst days of my life. Dad was just out of it. All we could do was whatever we could to make him comfortable.

“The reason we put him on hospice was he was beginning to have renal failure. I presume the stroke he suffered in 2002 was a contributing factor because he was in a pretty poor condition for 20 years.”

That Mills Lane was a respected and highly regarded referee is a given, and not just because he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Non-Participant category in 2013, which in and of itself is a story that bears telling. But it is the winding road this son of Deep South wealth and privilege undertook to success on his own terms that makes him unique, so much so that his history of obstinate self-discovery almost screams out for close-examination by a Hollywood screenwriter.

Mills Lane began life as the patrician scion of a banking dynasty in Savannah, Ga., with extensive holdings in South Carolina. How wealthy were the Lanes? So much so that the Mills B. Lane House in historic downtown Savannah, completed in 1907, was hailed as a “jewel of the antebellum South” when it was placed on the market in 2007 with an asking price of $7.6 million. It seems a safe bet that no other future referee was raised in a mansion that boasted a marble entrance, Corinthian columns, parquet floors, 29 handcrafted canvas murals, nine fireplaces, five bedrooms, eight full baths, three half-baths and a large, in-ground pool.

Young Mills’ father went so far as to have already paid his son’s tuition at a prestigious Midwestern university, where he was to study agriculture. But being a banker and/or gentleman farmer didn’t especially appeal to the son, so he chucked it all in 1958 to enlist in the Marines. He took up boxing during his service stint, becoming All-Far East welterweight champion. When his hitch was up, he enrolled at the University of Nevada in Reno which was reputed to have a boxing team of some repute. He won an NCAA boxing championship at UNR, went 10-1 as a pro and from there continued to make his mark as a deputy sheriff, district attorney, two-time judge of Washoe County Circuit Court and, of course, boxing referee.

It was as a referee, however, that Mills Lane began to make his mark not only nationally, but internationally, working such high-profile and controversial bouts as Muhammad Ali-Bob Foster (1972), Larry Holmes-Gerry Cooney (1982), the Evander Holyfield-Riddick Bowe II “Fan Man” fight (1993), Oliver McCall’s crying jag against Lennox Lewis (1997) and, most notably, the Evander Holyfield-Mike Tyson II “Bite Fight” (1997). It might have been coincidence or possibly fate when Lane got the assignment for Holyfield-Tyson II when the originally tapped ref, Mitch Halpern, backed out when Tyson’s handlers objected to him and was replaced by the guy known as a lightning rod for fights sure to be branded into the public’s memory.

“The visibility of the `Bite Fight’ made Mills even more mainstream,” recalled Marc Ratner, former executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission. “It almost seemed like he worked all the Super Bowls of crazy fights.”

Terry Lane said that the visibility of the “Bite Fight” was such that the producers of the (eventual) Judge Mills Lane TV show decided that their courtroom arbiter of justice just might be the same guy that had the stones to disqualify Tyson.

It was while at home in Reno, by himself, that Lane suffered the stroke that made him voiceless, unable to call out for assistance. Terry Lane is unsure how long he lay on the floor of his home, but the delay did not help.

“A few months earlier, our family had become bicoastal,” Terry Lane recalled for a story that appeared for TSS in 2014. “My brother had just begun high school in New York City after moving there from Reno. All of us were kind of going back and forth between Reno and New York. I had just started college in New York around that time. My mom, my brother and I were all back East and my dad was in Reno, by himself. We really don’t know how long it was before he was found. It might have been a day possibly as long as two days. We don’t know for sure.”

As if all that he already was facing weren’t enough, Mills had a fall in June 2013, almost to the day a full year before he was to be inducted into the IBHOF. His attendance for that event, which would have been considered extremely unlikely in any case, suddenly appeared to be impossible.

“When I got the call (from IBHOF executive director) Ed Brophy, I just assumed it would be Tommy and me going to Canastota and making a quick thank-you like we’ve done dozens of times before,” Terry said in 2014. “But Dad was really into it. I know he was very happy to be inducted into the Hall of Fame. He can’t speak, but he still can emote and be expressive.”

Amazingly – well, maybe not so amazingly given who and what Mills Lane always had been before the stroke – he threw himself into the task of learning how to walk again, however haltingly. And when the Lanes accompanied their father to central New York, the miracle that couldn’t possibly happen became reality.

“I could not believe that we were able to attend,” Terry said. “Ed Brophy and his team, God bless ’em, made our lives so much easier at that time. It was a highlight for Dad to be there during a time when he truly was a prisoner in his own body.

“When he first had the stroke in 2002, we were told that his life expectancy was five years, maybe. Another massive stroke, which was always possible, would just take him out. So, in our own way, our family has been mentally prepared for this moment for 20 years. But then my dad never followed any accepted timeframe from for the living of his life. He lived way beyond any doctor’s expectations, and in that time, he still was someone who not only was a disabled stroke victim, but he was getting older. He turned 85 on Nov. 12 of this year.”

In other words, what the stroke started finally was finished by the aging process that affects everyone. Rest in peace, Mr. Lane. In sickness and in health, you stood as a beacon of hope for everyone who understands that every fight is capable of being won to some degree.

Bernard Fernandez, named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Observer category with the Class of 2020, was the recipient of numerous awards for writing excellence during his 28-year career as a sports writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. Fernandez’s first book, “Championship Rounds,” a compendium of previously published material, was released in May of last year. The sequel, “Championship Rounds, Round 2,” with a foreword by Jim Lampley, is currently out. The anthology can be ordered through Amazon.com and other book-selling websites and outlets.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More