Articles of 2009

These Swabbies Deserve A Salute

To hear members of their curious and frequently underappreciated profession tell it, cutmen are like those “meatball surgeons” on M*A*S*H. Instead of hanging around an Army camp in olive-green fatigues, killing time and ogling nurses until the wounded arrived with the suddenness of a striking viper, guys (and the occasional gal) with Q-tips protruding from their mouths hang around in the corner wearing satin jackets, maybe applying an Enswell to a puffy eye between rounds until that swollen area breaks wide open and a stream of blood comes gushing out.

It’s when the action gets really hot, and their fighters can’t see for the leakage into their eyes, that cutmen are transformed into Hawkeye, Trapper John and B.J. Hunnicutt. The best of the breed learn to work fast, stay calm and handle pressure well. They don’t even have the benefit of ogling those scantily clad round-card girls; with only 60 seconds between rounds, there isn’t a moment to waste if they’re to stanch the bleeding.

Cutmen didn’t necessarily elevate the careers of such notorious bleeders as Henry Cooper, Chuck Wepner, Vito Antuofermo and Gaetan Hart, but they sometimes kept the gore down so that their guys could stay in the fight long enough to pull out victories that otherwise might have resulted in losses on cuts.

The late, great Ralph Citro, one of the rare cutmen to have been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame (although not primarily for that function), said his rise to prominence in the field was in direct correlation to the severity of the gashes incurred by one of his fighters, Canadian lightweight Gaetan Hart.

“The guy averaged, like, 43 stitches per fight,” Citro told me in 1989. “That’s where I got my education, and a lot of practice, as a cutman.”

Hart, whose face almost always looked like raw hamburger at the end of his bouts, was involved in another torn-flesh brawl when he took on Ralph Racine on May 7, 1980, in Montreal. Which meant, of course, that Citro was obliged to stick his fingers into those multiple wounds as if he were that little Dutch boy plugging so many leaks in the dam.

“By the end of the fourth round, both of Hart’s eyes were busted open,” Citro recalled. “His lip was cut, he had a cut underneath one eye and his nose was bleeding.”

Understandably, the referee and ring physicians kept glancing at Hart while wearing worried expressions. But Citro somehow kept patching Hart up, round after round, and he continued to answer the bell until he finally stopped Racine in the 12th round.

“After that fight I was wringing wet with sweat and blood,” Citro said. “I came down the steps and Gil Clancy (the Hall of Fame trainer who served as color commentator for the CBS telecast) said, `Great job, Ralph.’ And I said, `Yeah, I didn’t do too bad.’”

Legend has it that a 16-year-old beauty named Julia Jean Mildred Frances Turner was “discovered” by a Hollywood talent agent while sitting on a stool at Schwab’s Drug Store and wearing a tight sweater that accentuated her, um, more womanly attributes. The story probably was a creation of some studio press agent, but what is true is that the pretty teenager was renamed Lana Turner and went on to a long career as a movie goddess.

Citro working feverishly to minimize the damage to Gaetan Hart’s ruined face might not be the equivalent of Ms. Turner sitting on a stool at Schwab’s and sipping a soda, but the bottom line is more or less the same. Lana Turner went on to win an Academy Award, and Citro was invited to become the cutman for the Kronk Boxing Team by Emanuel Steward, who was in the audience that day in Montreal and was so impressed by his salvation of Hart that he gave the Blackwood, N.J., resident a dream shot to work with such high-profile Kronk fighters as Thomas Hearns, Jimmy Paul, Milton McCrory and Hilmer Kenty, among others.

Working the corner of the Kronk stable while wearing the renowned Detroit gym’s instantly recognizable gold-and-red colors, Citro soon was in demand as a cutman to the stars. He went on to service other celebrity clients, including Riddick Bowe for his Nov. 13, 1992, first fight with then-undisputed heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield.

A Holyfield left hook had Bowe’s right eye puffy and swollen in the very first round; an inadvertent thumb to the same eye in Round 8 closed it completely. But Bowe went out for the ninth round with the eye open, thanks to Citro’s expert ministrations, and he finished the fight without further damage.

“Thanks for saving my ass,” Bowe told Citro after he got the decision that made him king of boxing’s heavyweight mountain. The compliment, of course, was merely a figure of speech. Citro’s specialty was saving faces, not derrieres.

Citro, who was 78 when he died in 2004, was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2001 in the “Observer” category, which meant the honor stemmed more from his legacy as a record-keeper than as a cutman. In 1984 he founded Computer Boxing Update (now Fight Fax, Inc.) to accurately maintain fighters’ records, which often were embellished by promoters and public-relations flacks. No longer could a ham-and-egger with a 12-38 record and 17 consecutive knockout defeats be sold to unsuspecting audiences as being 38-12 and the heavyweight champ of some below-the-radar jurisdiction.

But whether Citro made it to Canastota as a cutman or a statistician, or some combination thereof, two things are clear: The very best cutmen too seldom become stars in their own right, and when they do it’s often the result of blatant self-promotion or simply being in the right place at the right time.

The same might be said of trainers, who in the galaxy of boxing’s support personnel are more widely lauded for the contributions they make to a fighter’s success than other members of the corner team. Angelo Dundee would have had a laudable career had the biggest names he worked with been Carmen Basilio, Willie Pastrano and Ralph Dupas, but it is the two superstars who employed him – Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard – that helped raise Ange to the status of an icon.

Conversely, one of the best boxing men with whom I’ve ever come into contact, Bouie Fisher, might have continued to anonymously labor for decades in musty North Philadelphia gymnasiums had not his most apt pupil, Bernard Hopkins, become one of the finest ring craftsmen of his era, in large part to Fisher’s tutelage during “The Executioner’s” formative stages. The skill and accomplishments of the fighter, more so than the expertise of his trainer or cutman, usually serves as the tide that lifts all boats.

One cutman who is primarily known for his work in that field (although he coached the 1959 USA Pan American boxing team) is Chuck Bodak, who was 92 when he died in February 2008. Bodak, who suffered a stroke in August 2007, had a nice mix of well-known fighters – among them, at one time or another, Oscar De La Hoya, Julio Cesar Chavez, Azumah Nelson and Jorge Paez – but his talent for minimizing the damage done by cuts might have been less noticed were it not for his own penchant for making himself part of the story.

With his shaved head, headbands, oversized, Elton John glasses and taped pictures of his fighters on that shiny chrome dome, Bodak was often more familiar to fight fans than some of the boxers whose corners he worked. He frequently was besieged for autographs as he made his way through crowded casino-hotels. That was no accident, either. Bodak, a onetime trainer who not only welcomed the attention, but sought it, wasn’t the kind to slip through back doors.

Not that Bodak had always made the grandstand play. It was his association with Paez, a former circus performer who went on to win the IBF featherweight championship, that convinced Bodak that it was in his best interests to aggressively seek the spotlight. And why not? Paez was a good fighter, but it was his outrageous ring attire, goofy hairstyles and flamboyant mannerisms that made him the Dennis Rodman of boxing, and a greater attraction than his not-inconsiderable talent otherwise would have dictated.

At Paez’s prodding, Bodak bought into the cult of personality and reinvented himself into the somewhat eccentric figure who couldn’t possibly be misidentified with anyone else.

Not as fortunate were some other very capable, very dedicated cutmen who did their jobs without fanfare. But while boxing insiders knew and respected them, the world at large was slower to catch on.

Just this past Sunday, two of the best cutmen ever to come out of maybe America’s best fight town, Philadelphia, belatedly received their due with their posthumous inductions into the Pennsylvania Boxing Hall of Fame.

Jimmy Wilson, also an accomplished trainer, was just 54 when he went to his eternal reward in 1958. He worked with, among others, Ike Williams, Lew Jenkins, Sonny Liston and Johnny Saxton, honing their moves and tending to their cuts.

Fifty-one years after his death, Wilson finally was honored as a Pennsylvania Boxing Hall of Famer along with Eddie “The Clot” Aliano, who was 77 when he died in 1996. Recognition delayed is always better than recognition denied.

“He wasn’t a jumpy person,” one of Philly’s busier current cutmen, Joey “Eye” Intrieri, said of Aliano, his professional role model. “He was very businesslike and in control of every situation. He never let anything get out of hand. That’s important because in a tough fight, things can get kind of crazy in the corner sometimes.

“Eddie had this ability to stay very calm and to take his time to do the job right, even though he was doing it as fast as he could. I know that sounds like a contradiction, but it really isn’t.

“The fighter has too much to worry about as it is without having to worry about a cut. The crowds yelling at him, the trainer’s yelling at him. Eddie would tell a nervous fighter, `That cut? Aw, it’s nothing. A scratch.’ I mean, it could be as wide as your thumb, but Eddie had this knack for convincing the fighter it wasn’t nearly as bad as it was. And you know what? He’d stop the bleeding, too.”

Perhaps someone should have reminded Evander Holyfield of all this prior to his April 23, 1994, heavyweight title defense against Michael Moorer, a bout for which the “Real Deal” was paid $12 million. Holyfield had a new trainer, Don Turner, who convinced him that cutmen were the “biggest scam in boxing,” and the employment of a cut-stopping specialist was a waste of the fighter’s money. Turner could pull double duty with no problem, he told Holyfield. But then Turner didn’t anticipate a worst-case scenario because, well, he and everyone else knew that Holyfield hardly ever bled during fights.

Thus Holyfield fired cutman Adolph “Ace” Marotta, who had been with him throughout his pro career. Marotta had gotten his start working with manager-trainer Lou Duva, and in the mid-1980s he snagged the prestigious gig as cutman for the Main Events stable of fighters that included such eventual world champions as Holyfield, Pernell Whitaker, Meldrick Taylor and Mark Breland.

Marotta was to have earned $25,000, or 1/180th (or .0053 percent) of his purse for the Moorer bout. But at Turner’s urging, he was cut, if you’ll pardon the expression, from Holyfield’s payroll and corner team.

What happened, of course, almost was to be expected. Holyfield was cut in the fifth round, and the wound reopened in each round thereafter.

“(Blood) kept getting in my eyes,” he complained after he lost his title on a 12-round, majority decision. For his part, the snubbed Marotta couldn’t help but issue an I-told-you-so.

“Don’t ever say to me, `My fighter doesn’t cut,’” Marotta said. “All fighters cut.”

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

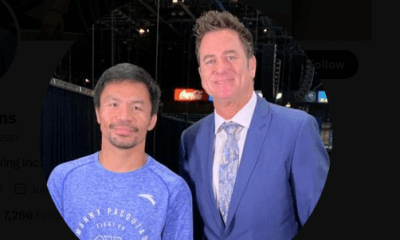

Featured Articles5 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons