Articles of 2006

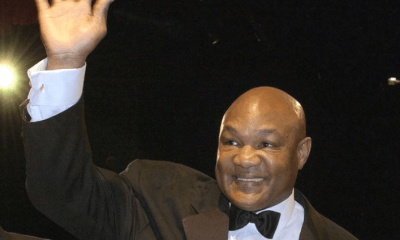

Ireland, Gerry Cooney and George Foreman

One afternoon two summers ago, Kevin McBride’s handlers had invited the media over to the South Boston Boxing Club to bear witness to his final sparring session before the Clones Colossus departed for Washington and the fight that would end Mike Tyson’s career.

It was my first visit since the L Street premises had been remade into a state-of-the-art boxing facility, and while the television cameras busily recorded McBride as he skipped rope over in the corner, I was inspecting the wall décor. On a bulletin board, amid the usual boxing posters, was a black-and-white photo of an obviously young pair of amateurs in headgear, slugging it out al fresco in a ring surrounded by trees and curious onlookers. The memories came flooding back.

“Is that what I think it is?” I asked trainer Jimmy Gifford.

“You got it,” grinned Gifford. “That was taken on the trip you guys took to Ireland back in what? 1989?”

Father Joe Young was at the time the parish priest in Southill, a poor ghetto in Limerick, which Ireland’s then-nascent economic boom had bypassed entirely. Amid desperate poverty he worked for over two decades with the kids in the area. Since meeting Father Joe I’d made several trips to Limerick, and had even taken both of my children to him to be baptized.

A veritable pipeline had been established between Boston and Southill. In the mid-80s, we brought teams of young athletes over to Ireland for competition, and, largely through the work of South Boston businessman Billy Higgins, over a hundred Southill kids comprising a children’s choir had flown to Boston to perform, living with local families on their visit.

Along with Kevin Haugh, the principal at St. Kieran’s School, and Tony DeLoughery, who had won All-Ireland titles at three different weight classes, Father Joe had also helped form the Southill Boxing Club, and when the phone rang in the early spring of 1989 it was to announce that he had put together an international boxing tournament which would be held in conjunction with an outdoor fair on the sprawling grounds of Adare Manor outside Limerick.

Father Joe wanted to know if we could bring a few American kids over to compete in the tournament. And, oh, by the way, why don’t you see if you can get Kevin Rooney to come over?

Thanks largely to his work with Mike Tyson, Rooney was at the time the most prominent rising star in American training circles. Father Joe’s thinking was that Kevin could help put on a few boxing clinics at area clubs, and that his presence at the Adare tournament would ensure a bigger turnout.

Getting the boxers would be the easy part. I rang up Billy Higgins, who immediately set the wheels in motion. Eddie Kelly’s PAL program in Southie had both boxing and basketball teams, and both Mayor Ray Flynn and the Police Commissioner, Mickey Roache, enthusiastically supported the idea.

I then phoned Rooney, who immediately agreed, with one stipulation: He wanted to bring his girlfriend, whom he’d been promising to take to Ireland someday. I successfully negotiated this part of the deal, and we were set to head over a few months later.

Less than a week before we were to fly, Rooney rang me apologetically to say that Kelvin Prather, a middleweight he was training up in Catskill, had unexpectedly advanced to the Golden Gloves nationals, and that he wouldn’t be able to make the trip after all.

When I relayed this news to Father Joe he was in a panic.

“But people are coming from all over the country for this,” he said. “What about the clinics at the boxing clubs? What are we going to do?”

I didn’t have a clue, but Father Joe had a suggestion.

“Would you ever ring Gerry Cooney?” he asked. “Maybe he’d do it.”

Father Joe had met Cooney exactly once, when I’d taken him along to one of those breakfast-cum-press conferences to boost his fight for the ‘linear’ heavyweight championship against Michael Spinks a year earlier. Gerry had retired after being knocked out in that fight, but he was still the most visible Irish-American boxer in captivity, thanks to the residue of his 1982 title fight against Larry Holmes, in which he had led before succumbing in the 13th round when trainer Victor Valle jumped into the ring to rescue him from further punishment.

I rang Cooney to ask if he could possibly make the trip to Ireland.

“When?” he asked.

“Wednesday,” I told him.

There was a long pause.

“Let me call you back in an hour,” he said.

An hour later Cooney had enlisted in the project. Like Rooney, he’d asked if we could find an extra plane ticket, and, thanks to the defection of Kevin and his girlfriend, we had one.

Cooney’s traveling companion was a large fellow named Big John, a Vietnam veteran and a former New York City cop. Since the Gardai Soichana – the Irish police force – were helping to sponsor the boxing tournament at Adare Manor, this actually provided a nice touch.

On the flight over I learned more about the nature of the relationship between Irish Gerry and Big John. Following his defeat by Spinks, Cooney had battled the temptations of drugs and alcohol, and had only recently completed a 12-step program. To all outward appearances Big John was his “minder,” as the Irish would describe a bodyguard, but he was also his counselor and sobriety confidante, there to help keep him on the straight and narrow.

We’d flown into Dublin, hoping to drum up interest in the Adare event with a press conference at Buswell’s Hotel. The hostelry was directly across the street from the Dial Eirann, the national parliament, and a chance meeting as we were leaving produced a photo op for a picture that ran on the front pages of every newspaper in Ireland the next morning: Cooney and then-Prime Minister Charles Haughey, each with his dukes up and apparently prepared to slug it out on the front steps of Buswells.

The next morning I went out for a game of golf with the Irish musician Finbar Furey, while Gerry and Big John took an escorted tour of Dublin with a taxi driver friend of ours, Brendan Freeman. At Finbar’s insistence, Brendan drove Cooney out to Kilcullen in County Kildare so he could see Dan Donnelly’s arm.

Donnelly had been a great bare-knuckle champion of the early 19th Century, with the Prince of Wales his primary patron. After his death in 1820 his body had been snatched by graverobbers, who in a common practice of the day sold his remains to the College of Surgeons in Edinburgh. When his friends learned what had happened they set sail for Scotland, but by the time they arrived the cadaver had been thoroughly dissected and all they could find was his right arm. They brought it back to Dublin, and, two centuries later, it sat, in a mummified state, in a place of honor behind a glass case in a Kilcullen pub called the Hideout. (Seventeen years later Donnelly’s arm flew to America in the cabin of an Aer Lingus jet, and currently represents the centerpiece of the “Fighting Irishmen” exhibit at the Irish Arts Center in New York.)

We rendezvoused in the town of Monasterevin, after which Finbar drove Gerry, Big John, and me to Limerick before proceeding to Galway, where the Furey Brothers band had a gig that night. By the time we got to Limerick Cooney had fallen thoroughly under the spell of the Prince of Pipers, and that night he decided that we should hire a car to drive us to Galway and back for Fureys’ concert.

The venue was noisy and the music lively, and even though the booze was flowing freely all around them Gerry and Big John enjoyed themselves immensely, and got a big round of applause when Finbar introduced them from the stage.

We were leaving the club after the show when one of those inevitable closing-time street fights broke out on the sidewalk. Gerry ordered the car to a halt and jumped out to play peacemaker. Insinuating himself between the would-be combatants, he tried to hold them at arm’s length until one of them got loose and delivered a fierce head-butt to the skull of the other. Blood was spouting out of the fellow’s forehead and his girlfriend sprang into action and leapt on the other guy’s back. The situation was getting hopelessly out of control, but Cooney was still convinced he could be Mother Teresa and bring peace to the streets of Salthill.

Toward that end he had grabbed the more aggressive guy in a bear hug. He was still holding him like that when the guy’s opponent picked up an empty Guinness barrel and brought it crashing down over the head of his immobilized opponent.

“Come on, Gerry, let’s get out of here,” I pleaded, and Cooney finally gave up.

“Did you see that head-butt?” he exclaimed on the way back to Limerick. “God, I hate the sight of blood.”

The next day in Limerick Father Joe trotted out the Children’s Choir for a special welcoming concert for Gerry and the South Boston kids. We spent the next couple of days visiting boxing clubs around the area, where Gerry put on clinics with the Irish coaches. Nights we tended to spend in the Brazen Head in downtown Limerick. Cooney wasn’t drinking, but there were lots of pretty young Limerick lasses about.

“What I need to do over here,” he said, “is find myself a wife.”

The Southill Boxing Club was coached by Tony DeLoughery, who had at various times won All-Ireland titles at middleweight, light-heavyweight, and heavyweight. Five years earlier, when he was the reigning Irish middleweight champion, he had visited the states with Father Joe, and I’d brought the two of them down to the Cape meet Marvelous Marvin Hagler the morning Marvin and I flew out of Hyannis to begin the promotional tour for his fight against Roberto Duran.

In addition to the contingents from Southie and Southill, there were visiting teams from England and France participating in the tournament. DeLoughery had commandeered an army vehicle to transport the ring to Adare, and set it up in a lush meadow in the shade of a large oak tree.

“Good idea,” I said when I saw the venue. “Were you thinking of the shade the tree would provide?”

“No,” replied Tony, “but it might help a bit if it rains.”

The American entry consisted of three boxers, Jamie Strong, Pat Mallard, and Jimmy LeBlanc. Only 15, Jimmy had no trouble making 106 pounds back then. Several years later he would turn pro, accumulating a career record of 11-10-4.

“We were over there for ten days, and stayed with Irish families,” recalled LeBlanc, who formed some lasting friendships on the trip. “I only had one fight in the tournament, against an Irish kid named Paul McGuigan, and I won.”

“We had a great time,” said Jamie Strong, then a 132 pound 16-year-old, now a successful South Boston attorney. “Jimmy and Pat were staying with a family in the city, but I stayed with an Irish couple who lived out in the country, and every morning when I got up there was this huge breakfast waiting for me. It was an experience I’ll never forget.”

Strong also had one bout at Adare.

“I thought I’d won, but the Irish kid got the decision,” he said. “I believe you wrote at the time that it could have gone either way.”

Billy Higgins had also arranged for a basketball team from Southie to fly to Limerick. The squad was a bit short on numbers, so the boxers filled in as substitutes, and acquitted themselves well.

“I think I scored four points in two games,” said Strong.”

Fortunately, none of the basketball players had to double as pugilists.

Being held in conjunction with the fair meant that the boxing tournament had a ready-made audience. Some stood rooted to their spots and watched fight after fight, while others strolled by, stopped to watch a bout or two, and moved on, but there were always at least a few hundred spectators for any given bout. Medieval knights in full battle costume rode by on horseback, passing within a few feet of the boxing ring. Across the expanse of green meadows, crumbling castle walls were visible in the background.

“It was almost surreal,” recalled Jamie Strong.

At the conclusion of the boxing event, Cooney climbed into the ring and helped present the trophies. Once it was over we repaired to the bar at the Dunraven Arms across the road from the manor. Many years later, the same hostelry would serve as the venue when Irish millionaire sportsman J. P. McManus hosted a dinner welcoming George Foreman to Ireland.

Before our 1989 trip Cooney’s Irish connections were somewhat nebulous. He fought under the nom de guerre “Irish Gerry” and wore a Donegal tweed cap to his weigh-ins, but in the early 1980s when the late Joe Flaherty asked Irish Gerry which county his people hailed from, Cooney smiled and replied “Suffolk.”

Through a bit of research he had learned that his ancestral home was a small village in County Mayo, and had actually made arrangements to visit there. Now, a day before he was to fly back to the states, time was getting short and he decided to postpone the visit.

When he reached some long-lost distant cousin to inform him that he wouldn’t be coming, the relative moaned “Ah, but Gerry, there’s hundreds of people waiting to meet you in the town square. They’ve organized a big reception for you.”

Now, Gerry realized, he had to go.

On such short notice the only way Cooney was going to make it to Mayo and back was to fly. He hastily chartered a helicopter at his own expense, and he and Big John jumped in.

The chopper got about 500 feet off the ground when Big John ripped off his seatbelt and, banging off the walls, began to howl like an animal. Fearful that he might wreck the helicopter, the pilot hastily descended and discharged him on the tarmac.

Big John had always been sketchy about the nature of his imprisonment and we’d all been too polite to press for details, but it turned out the way he got to be a POW in the first place is that the Vietcong shot down the helicopter he was riding in. In the peaceful tranquility above County Clare he’d been seized by a flashback.

I learned all of this when I arrived at Shannon for my own return to the US that day. Cooney was off in Mayo, but Big John was planted in the airport bar. Remarkably, given the circumstances, he was drinking coffee.

Foreman’s 1999 Limerick visit is still recalled as a magical interlude, one of the most memorable moments in the city’s history, and it indirectly had its genesis at that long-ago boxing tournament at Adare Manor.

A few months after returning from Ireland, Gerry Cooney found himself inexorably drawn back to the ring, and in January of 1990 he made his comeback against Foreman. Gerry invited Father Joe to attend the fight as his guest, sent him a plane ticket, and even had a limo waiting in Newark to whisk him down to Atlantic City.

A few nights before the fight we ran into Foreman at Caesars. The two men of the cloth immediately took to one another. Big George confessed that he’d always wanted to go to Ireland and promised to come to Limerick someday.

That didn’t happen for nearly a decade, and by the time it did, Foreman had shocked the world by regaining the heavyweight title at the age of 45, and had in the process become the most recognizable boxer on the planet. One day we were sitting on the front porch of his ranch in the East Texas hill country and when the conversation turned to Ireland. George announced to me that he was ready to make his pilgrimage.

“You make the arrangements,” he told me. “Next spring we’ll go to Ireland.”

Foreman prepped for the Limerick trip by reading Frank McCourt’s “Angela’s Ashes,” and before we left he asked me “is it still like that?”

“Not everywhere,” I told him, “but in Southill it might be worse. Imagine the most desperate ghetto in Houston, give the kids blue eyes, and you’ve got it.”

George spent the day touring Southill, and in the afternoon shared the pulpit with Father Joe at the Holy Family Church. That evening, far removed from the slums that were the priest’s hardscrabble parish, George finished his dinner at McManus’ banquet and then asked Father Joe to accompany him to his room. There, in privacy and away from the television, he asked the priest which three of his many projects could best be helped by funding.

Father Joe ticked off the names of the soccer team, the marching band, and the Southill Boxing Club. With that, Foreman unhesitatingly wrote out three checks of $20,000 apiece to those entities. God knows it was an uphill battle, but the money kept them going for a while. There’s still a life-sized mural of Foreman adorning one of the walls at a since-abandoned Southill school. And just think: if Kelvin Prather had lost in the 1989 Gloves regionals none of it might have happened.

Articles of 2006

Peter/Toney Ii: Peter Has The Brutal Punch

Samuel Peter claims he has dynamites in my two hands?

Heavyweight contenders Samuel “The Nigerian Nightmare” Peter and James Lights Out? Toney get it on a second time this Saturday from the Seminole Hard Rock in Hollywood, Fla. (Showtime).

The hard-slugging Peter, unlike Toney, is one of those strong, silent types notorious for letting their fists to the talking one the opening bell sounds, but the Nigeria Nightmare is as confident as ever and determined to turn Lights Out’s lights out for good.

I have got dynamites in my two hands,? said Peter, according the Lagos, Nigeria Vanguard, and I will crush James Toney once and for all. The Toney camp made the mistake of their lives by protesting and seeking a rematch. I am ready to teach him a bitter lesson.?

Sam Peter walked away with the W for Peter/Toney I at the Staples Center in LA last September, but it was by disputed split decision a verdict so disputed, there was even a dispute about the dispute which forced the WBC’s hand into mandating Saturday’s rematch.

Samuel Peter is the biggest thing to hit African boxing since Ghanaian superstar Azumah Nelson rocked the feather and junior welterweight divisions. The President of the Nigeria Boxing Board of Control, Prince Olaide Adeboye, admitted, according to allAfrica.com, We are rooting for Samuel Peter, of course. He is one boy we believe in to bring back the country’s lost glory in professional boxing. I am personally making arrangement to be at the ringside to see him fight Toney again. I was at the first fight in Los Angeles in September.

Peter has the brutal punch, and to me he was the clear winner of the first fight. But the WBC Board of Governors, of which I am a member, voted 21-10 for a rematch. There was nothing those of us Africans on the board could do in the circumstances. But I believe Peter will confirm he is better than Toney and will then go ahead to meet the champion and claim the belt for Nigeria and Africa.?

Articles of 2006

The Sweet Science P4P Rankings for Asia

There are claims that boxing is dying. Hogwash. The heavyweight division isn’t the only division in boxing and 2007 promises to be a banner year in boxing; especially for boxers hailing from Asia.

While Asia isn’t Vegas or Atlantic City, it is a region packed of diamonds in the rough; undiscovered gems and potential superstars who wait for their moment in the sun.

The Sweet Science P4P Rankings – Asia

1) Manny Pacquiao – There’s no way to dispute Pacquiao is the best fighter in Asia, if not all of boxing. He’s exciting, he wins with Je Ne Sais Quois and is definitely “the man” in boxing.

2) Pongsaklek Wonjongkam – Although his competition leaves much to be desired, his longevity and skills are undeniable. He is currently Thailand’s only world champion and is undefeated in ten years. Need I say more?

3) Chris John – A victory over Juan Manuel Marquez, however controversial, shows he belongs at the top of the heap. He easily outpointed Renan Acosta to close out 2006 and should have no trouble defending against Jose Rojas in February. A fight with Pacquiao would not be a good move on his part but a rematch with Marquez would not hurt – especially if he defeats the Mexican again.

4) Hozumi Hasegawa – Hidden away in Japan, Hasegawa is a sharp punching southpaw who put former champion Veeraphol Sahaprom to sleep. He recently bested Genaro Garcia and his herky-jerky style will give fits to any one who steps in the ring with him.

5) Masomori Tokuyama – Tokuyama has never shied away from a good fight and although he only fought once in 2006 (UD12 Jose Navarro), he ledger shows wins over Katsushige Kawashima (twice), Gerry Penalosa (twice) and In Jin Chi (twice). A fight with Hozumi Hasegawa is a distinct possibility in 2007.

6) Nobuo Nashiro – With only seven fights under his belt he took on WBA champion Martin Castillo – and defeated him. Although he’s only fought a total of nine fights, nearly all have been against quality opposition. A victory in a rematch with Castillo would cement his claim as the king of the 115-pound division.

7) Yukata Niida – This light-hitting minimumweight defended his title twice in 2006, winning a technical decision against unbeaten Eriberto Gejon (Tech Win 10) and the other on points over Ronald Barrera (W 12). Scheduled to meet Katsunari Takayama early next year – the best has yet to come for this WBA belt holder.

8) In Jin Chi – Won back the title he lost to Takashi Koshimoto in January from Rudolfo Lopez. While there’s little uncertainty to his skills, at thirty-three, 2007 may provide some insight as to just how much he has left.

9) Yodsanan Sor Nanthachai –Sor Nonthachai is an exciting, top-shelf fighter with an iron chin. Has no trouble making mincemeat of mid-level opposition and deserves a title shot in 2007. Time is running out.

10) Rey Bautista – He’s young, relatively inexperienced in big-time boxing, but will continue to shine in 2007. One of the better prospects in boxing, he should snag a title in 2007.

Asian Fighters Ranked in Ring Magazine

Pound for Pound:

Manny Pacquiao (Philippines): #2

Jr. Lightweight

Manny Pacquiao (Philippines): #1

Yodsanan Sor Nanthachai: #9

Featherweight

Chris John (Indonesia) #1

In Jin Chi (Korea) #3

Takashi Koshimoto (Japan) #5

Hioyuki Enoki (Japan) #7

Jr. Featherweight

Somsak Sithchatchawal (Thailand) #4

Bantamweight

Hozumi Hasegawa (Japan) #2

Veeraphol Sahaprom (Japan) #3

Ratanachai Sor Vorapin (Thailand) #6

Poonsawat Kratingdaenggym (Thailand) #10

Jr. Bantamweight

Nobuo Nashiro (Japan) #1

Katsushige Kawashima (Japan) #7

Pramuansak Phosuwan (Thailand) #10

Flyweight

Pongsaklek Wonjongkam (Thailand) #1

Takefumi Sakata (Japan) #7

Daisuke Naito (Japan) #10

Jr. Flyweight

Koki Kameda (Japan) #1

Minimumweight

Yukata Naiida (Japan) #2

Eagle Kyowa (Japan/Thai) #4

Katsunari Takayama (Japan) #5

Rodel Mayol (Philippines) #7

Boxing in Thailand

There’s no shortage of boxers in Thailand. With a huge pool of Muay Thai fighters to draw from and several talented amateur boxing prospects turning pro after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Thailand seems destined to remain a boxing powerhouse in Asia.

The country is known for having tough, determined and disciplined fighters who give their all whenever the step in to the ring. However, consistently losing while fighting abroad and padding their records with no-hopers has done nothing to enhance their reputation.

Whether because of a lack of marketability, a lack of funds or their unwillingness to travel abroad, the vast majority of boxers from Thailand remain a mystery to fans in the west. If anything though, the boxing scene involving Thai fighters will be active. In fact, it’s one of the most active in the world; since 2000, the number of fights has nearly doubled in the country.

The Sweet Science P4P Rankings – Thailand – August 2006

1) Pongsaklek Wonjongkam

2) Poonsawat Kratingdaenggym

3) Somsak Sithchatchawal

4) Wandee Singwancha

5) Sirimongkol Singwancha

6) Yodsanan Sor Nanthachai

7) Veeraphol Sahaprom

8) Pramuansak Phosuwan

9) Terdsak Jandaeng

10) Oleydong Sithamerchai

Current Sweet Science P4P Rankings – Thailand

1) Pongsaklek Wonjongkam (Flyweight) – Definitely the top dog in Thailand

2) Yodsanan Sor Nanthachai (Super Lightweight) – He’s a seasoned fighter who has proven himself in the big-time. He’s one Thai who can fight outside of Asia. He has an abundance of skills and one-punch power. His overall ability and ease in dispatching anyone other than championship caliber get him the runners-up spot.

3) Poonsawat Kratingdaenggym (Super Bantamweight) – After losing to Vladimir Sidorenko he’s bounced back. He’s young, he can punch, but the former interim champion needs to prove himself against a name fighter.

4) Somsak Sithchatchawal (Super Bantamweight) – Was his win over Monshipour a fluke or was Celestino Caballero just that good? Did Sithchatchawal catch Monshipour at the right time and can he rebound from the devastating loss? The jury is still out.

5) Wandee Singwancha (Flyweight) – He doesn’t have much of a punch which will be his downfall in the end. He can box, as was evidenced in his recent victory over Juanito Rubillar, but this won’t be enough. He can no longer make the Jr. Flyweight limit and with no punch he’ll have a hard time competing against the “big boys.” Although he’s now rated second by the WBC, he doesn’t deserve to be.

5) Sirimongkol Singwancha (Super Lightweight) – Get this guy a fight. He’s better than Jose Armando Santa Cruz and would have beat up Inada had the fight taken place. He’ll fight anyone but his biggest obstacle is staying motivated fighting tomato cans in Thailand. Like many Thais, he needs a fight against a name opponent.

6) Wandee Singwancha (Flyweight) – He doesn’t have much of a punch which will be his downfall in the end. He can box, as was evidenced in his recent victory over Juanito Rubillar, but this won’t be enough. He can no longer make the Jr. Flyweight limit and with no punch he’ll have a hard time competing against the “big boys.” Although he’s now rated second by the WBC, he doesn’t deserve to be.

7) Pramuansak Phosuwan (Super Flyweight) – A genuine tough guy. Always calm and focused no matter how heated the battle. But at thirty-eight, he’ll be in trouble should he fight one of the division’s elite.

8) Veeraphol Sahaprom (Bantamweight) – Will be lucky to get another crack at the title. Although he has a puncher’s chance of winning a belt, that’s about all he has left at this point. A third shot at Hasegawa is unlikely.

9) Oleydong Sithamerchai (Minimumweight) – He’s fought better than the usual opponents faced by Thais at his level and he moves up one spot with the departure of Terdsak Jandaeng. He lacks the punch and is in the wrong division to become a superstar. He’ll need to defeat a name opponent to convince me.

10) Saenghiran Lookbanyai / Napapol Kittisakchokchai (Super Bantamweight) – These two square-off in early March, supposedly to see who deserves a shot at Israel Vasquez. Kittisakchokchai has the edge in experience but some feel Lookbanyai has the edge in heart and is the favorite.

Neither has defeated a top twenty fighter and yet are ranked number one and two respectively in the WBC’s world.

In Kittisakchokchoi’s lone shot at the big-time, he was TKO’d in 10 by Oscar Larios. His dreadful performance against Larios and lack of quality opposition leads me to believe Saenghiran might have more of a shot at beating him than some suspect. Regardless, neither of them lasts longer than six rounds with Israel Vasquez.

Honorable Mention: Wethya Sakmuangklang, Denkaosan Kaovichit, Devid Lookmahanak, Nethra Sasiprapa, Chonlatarn Piriyapinyo, Pornsawan Kratingdaenggym

Thai Fighters Ranked in Ring Magazine

Pongsaklek Wonjongkam: #1 Flyweight

Pramuansak Phosuwan: #10 Jr. Bantamweight

Veeraphol Sahaprom: #3 Bantamweight

Ratanachai Sor Vorapin: #6 Bantamweight

Poonsawat Kratingdaenggym: #10 Bantamweight

Somsak Sithchatchawal: #3 Jr. Featherweight

Yodsanan Sor Nanthachai: #9 Lightweight

Articles of 2006

Iceman Stops Tito Ortiz Win Streak

LAS VEGAS—UFC light heavyweight champion Chuck “Iceman” Liddell’s fists proved too much for Huntington Beach’s Tito Ortiz who was stopped in the third round before a sold out crowd at the MGM Garden Arena on Saturday.

The punching machine Liddell (20-3, 13 KOs) repeated his victory in UFC 66 over the much-improved grappler Ortiz who has improved his punching and blocking. Ortiz was trying to avenge his loss of April 2004.

Despite all the new weapons displayed by Ortiz it wasn’t enough as Liddell pummeled the former champion and retained his title with a technical knockout at 3:59 of the third round. Referee Mario Yamasaki stopped the bout.

“This was the most satisfying victory of my career,” said Liddell, 36, of Santa Barbara. “Tito came back real tough.”

Ortiz (15-5, 8 KOs), a former wrestler, worked on his boxing technique knowing he would need it against the former boxer Liddell. But Liddell’s experience allowed him to find the right moment to pounce on Ortiz.

“I had him hurt, I just kept throwing punches,” said Liddell who also knocked down Ortiz in the first round with a left hook.

Ortiz was gracious in defeat.

“Chuck is the best fighter Pound for Pound in the (mixed martial arts) world,” said Ortiz, 31, who suffered a gash on the side of his left eye from a punch. “I’m disgusted by myself. I let my fans down.”

Other bouts

Underdog Keith Jardine (12-3-1) knocked out Forrest Griffin (13-4) at 4:41 of the first round in their light heavyweight showdown. A right uppercut followed by a left hook wobbled Griffin who was sent to the floor by a barrage of punches. On the ground Jardine landed right after right until referee John McCarthy stopped the fight for a technical knockout.

“I couldn’t believe he was hurt,” said Jardine about Griffin who is known for his resiliency. “I was so nervous coming into this fight, but now I know I belong here.”

Canada’s Jason McDonald (18-7) choked out Chris Leben (15-3) in a middleweight bout that was up for grabs. Though Leben seemed to control the fight with stunning left hands, once the fight went to the ground McDonald managed a chokehold at 4:03 of the second round. Referee Steve Mazagatti saw Leben was unconscious and stopped the fight.

Former UFC heavyweight champion Andrei Arlovski (12-5) caught Brazil’s Mario Cruz (2-2) with a sneak right hand while both were tangled on the ground. Then the Belarusian pummeled Cruz until referee Herb Dean stopped the fight at 3:15 of the first round.

Third season winner of the Ultimate Fighter television reality season Michael Bisping (12-0) of Great Britain won by technical knockout over Eric Shafer (9-2-2) at 4:29 of the first round. A knee knocked Shafer groggy then Bisping knocked him to the ground and pounded him. Referee Mario Yamasaki stopped the bludgeoning.

Thiago Alves (16-4) caught Peru’s Tony De Souza (15-5) with a knee as he attempted to dive for his legs in a welterweight contest. After that it was pretty much over as Alves pummeled De Souza at 1:10 of the second round forcing referee John McCarthy to halt the bout.

Gabriel Gonzago (7-1) proved too strong for Carmelo Marrero (6-1) in a heavyweight bout. At 3:22 of the first round Gonzago of Massachusetts manipulated his way into arm bar forcing Pennsylvania’s Marrero to tap out.

Japan’s Yushin Okami (19-3) pounded Georgia’s Rory Singer (11-6) into submission at 4:03 of the third round of a middleweight bout. Okami seemed the more-rounded fighter with effective kicks to the head and more accurate punching.

Christian Wellisch (8-2) jumped to a quick start with an accurate left hook that rattled Australia’s Anthony Perosh (5-3) in a heavyweight bout. During the first round it seemed the Sacramento fighter might end the fight but the Aussie hung tough. Wellisch won by unanimous decision.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Paean to George Foreman (1949-2025), Architect of an Amazing Second Act

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: The Wacky and Sad World of Livingstone Bramble and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 319: Rematches in Las Vegas, Cancun and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRingside at the Fontainebleau where Mikaela Mayer Won her Rematch with Sandy Ryan

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoWilliam Zepeda Edges Past Tevin Farmer in Cancun; Improves to 34-0

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoHistory has Shortchanged Freddie Dawson, One of the Best Boxers of his Era

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 320: Women’s Boxing Hall of Fame, Heavyweights and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Las Vegas where Richard Torrez Jr Mauled Guido Vianello