Articles

Holmes-Cooney: The Last Great Race Fight

Thirty years later, I can still see the bemused face of a high school acquaintance as he walked off after paying me the $10 I’d won in our bet on the big fight. I had Larry Holmes; he had Gerry Cooney. He wasn’t a boxing fan, but on June 11, 1982, you didn’t have to be to care about this heavyweight bout, pitting the black champion, Holmes, against the white challenger, Cooney.

Thirty years later, I can still see the bemused face of a high school acquaintance as he walked off after paying me the $10 I’d won in our bet on the big fight. I had Larry Holmes; he had Gerry Cooney. He wasn’t a boxing fan, but on June 11, 1982, you didn’t have to be to care about this heavyweight bout, pitting the black champion, Holmes, against the white challenger, Cooney.

That simple white/black equation turned the fight into a national obsession and an uncomfortable racial drama that had some questioning how far the nation had really come on such matters.

If the undefeated Cooney could beat Holmes, he would become the first white American heavyweight champion in a quarter-century. Time magazine put Cooney on its cover with Sylvester Stallone, whose Rocky III was just hitting theaters. Sports Illustrated also led with Cooney on the cover, relegating Holmes to the inside flap. Whites rallied around Cooney, whose managers boasted that he’d become “the first billion-dollar athlete.” Holmes, also undefeated against more formidable opposition than Cooney had faced, was an afterthought, or worse.

Bad timing and bad public relations made the going hard for Holmes. He was Muhammad Ali’s successor as heavyweight king, and the task of succeeding a great champion had a long and unhappy history in boxing: think Jim Corbett, Gene Tunney, Ezzard Charles, or Joe Frazier. Worse, Ali’s inability to stay retired had forced Holmes to accept his challenge, and Holmes’s dreary drubbing of his former mentor over 10 rounds—he notably held back from punishing Ali more—didn’t exactly win him adulation in the black community. A proud and self-sufficient man with a disarming tendency to speak frankly, Holmes grew more bitter, not less, as champion, especially as he saw himself denied the respect he felt he’d earned. Exactly what this respect would entail he never made clear.

Holmes had come up poor in Easton, Pennsylvania, hiding small change in flowerpots to keep it from the grasping fingers of his own hard-up siblings. He dropped out of school in the seventh grade to work in car washes and steel mills and drive trucks. He made $63 for his first pro fight and slender four-figure purses for years, even as his record swelled to 26-0. Only when he became champion did he begin to see real money.

What Holmes saw in Gerry Cooney was a fighter who’d been spared his hard road. Cooney, from Huntington, Long Island, had won 25 fights without a loss, 22 by knockout, many within the first three rounds. He had a lethal left hook, but his talents waited on a genuine test. Cooney had won his recent fights in pulverizing fashion against big names—Jimmy Young, Ron Lyle, and Ken Norton—but all were men well past their fighting primes, chosen to add luster to Cooney’s record and sell him to the public. It worked: the Cooney bandwagon became unstoppable.

Holmes couldn’t resist pointing out how race had propelled Cooney’s rise. He called Cooney the Great White Hoax or the Great White Dope: “If the man was black, he wouldn’t be nowhere. You know it, I know it. Everybody knows it.” Holmes’s anger embittered many whites towards him, and some cast him as a racist. In truth, Holmes moved in integrated circles, hired white and black employees for his burgeoning business empire, and generally regarded people, of whatever color, with the skepticism that had helped him survive.

In his 1998 autobiography, Holmes attributed his outbursts before the Cooney fight to the racist intimidation he was subjected to as the fight approached—including vandalism to his house and death threats. But Holmes was denigrating Cooney long before the fight was signed—a year, even two years earlier, during which time the two had some unpleasant run-ins. Cooney and his well-greased path to wealth, along with his friendly media coverage and effortless popularity, scraped Holmes raw, and the champion’s rage contributed significantly to the fight’s charged racial atmosphere.

Even if Holmes had behaved with Joe Louis-like restraint, white Americans might have rooted for Cooney anyway. There hadn’t been a white heavyweight champion in so long that identifying with Cooney as an Irish-American, or just a white American, was inevitable. After all, boxing had long been built on ethnic clashes, with each tribe rooting for its own. Unfortunately, clashes between black and white tended to inspire the worst tendencies in people—as boxing history well showed.

The most infamous example had come over 70 years earlier, when Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion, defended his title against former champ Jim Jeffries in Reno. Jeffries had wanted to stay retired, but implored to defend the honor of the White Race—and tempted by an unthinkable $100,000 payday—he relented. After Johnson beat him badly, race riots erupted across the country. It would be 22 years before another black man was allowed to fight for the title. And when he did, Joe Louis inaugurated an era of black heavyweight dominance interrupted only by Rocky Marciano (an all-time great) and Sweden’s Ingemar Johansson (a novelty champion). So the black/white racial drama around the heavyweight division lessened somewhat. In fact, the most divisive boxing event in decades had been a fight between two black men, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier.

Until Holmes-Cooney.

The idea that a white fighter might actually win the title—and against a black champion, to boot—made the bout something like a real-life version of Stallone’s Rocky movies. Both men were guaranteed $10 million, and the bout, like all big fights then and now, would not be available on free TV. Back then, before the days of pay-per-view, that meant closed-circuit television, available for the price of a ticket to a movie house, auditorium, or arena.

Even with huge public interest, the fight’s promoters couldn’t resist stoking passions. “This is a white and black fight,” barked Don King, Holmes’s brilliant and amoral promoter. “Anyway you look at it, you cannot change that. Gerry Cooney: Irish, white, Catholic.” Cooney’s ingenious huckster managers, Mike Jones and Dennis Rappaport—collectively known in the media as the Whacko Twins—fanned the flames, too. “I do not respect Larry Holmes as a human being,” Rappaport said. “I don’t think he’s carried the championship with dignity.” They pushed Cooney, with little subtlety, as white America’s champion. “He’s not the white man, he’s the right man,” Rappaport liked to say—combining racial appeal with racial deniability in one neat phrase. No wonder he used it so much.

Holmes began receiving death threats in the run-up to the fight, some of which came over his home phone: “Don’t start your car tomorrow, nigger.” He was “determined not to be intimidated by the collective desire of white America to see me get beat,” he wrote later in his autobiography. As the fight neared, Holmes decided to double down: he brought the Rev. Jesse Jackson into his camp. Jackson, it was said, might help defuse tensions—though the reverend wasn’t exactly renowned for his tension-defusing gifts. He made his way toward the ring with the Holmes entourage, clad in Holmes red.

*******?

The thermometer had hit 100 earlier in the day, but by fight time, the temperature in Las Vegas had dropped to 89 degrees—though with the lights and cameras, it would be hotter than that for the fighters. Holmes and Cooney made their way to the ring, Cooney first, while overhead, from the rooftops of every major hotel overlooking Caesar’s Palace, police snipers kept a keen eye out for trouble. Threats had come in against both fighters. “I felt a palpable feeling of danger out there,” HBO’s Larry Merchant said.

In a move that broke with boxing precedent, Holmes, the champion, was announced first, receiving audible boos. Cooney was announced next, to a slowly building crescendo of cheers. None of the seasoned boxing observers at ringside could recall a fight in which the challenger had been announced last. The clear intent was to allow Cooney’s crowd support to swell. It couldn’t have helped Holmes’s mood, but the champion somehow found it in himself to say to Cooney, as they received the referee’s instructions at ring center: “Let’s have a good fight.”

In those days before 24/7 sports coverage, if you didn’t attend the closed-circuit screenings, the only way to get live updates was to listen to the radio. In the New York area, 1010 WINS-AM—“All-news radio: you give us 22 minutes, and we’ll give you the world”—served that function. For Holmes-Cooney, the station announcer would break in every 5 minutes or so with news on the fight.

The first round, according to WINS, was a cautious one for both fighters, but Holmes began to get his potent left jab working. His fight plan was evident from the start: move laterally, almost always to his left, away from Cooney’s left hook; work the left jab to control the tempo, throw off Cooney’s rhythm, and set up other punches; and stay off the ropes and out of corners. Cooney walked toward Holmes, trying to cut off the ring and set him up for the knockout blow, the left hook. In the second round, though, Holmes showed his own punching power. He threw boxing’s oldest combination, the left jab-right cross—“the old one-two”—and the right landed flush on Cooney’s jaw as he was moving in. The punch lifted Cooney’s left leg off the canvas and threw his balance into a crazed few seconds of gyration, as he wobbled weirdly away from Holmes like a spinning top and then went crashing to the floor. Not seriously hurt, Cooney took the referee’s mandatory eight-count and finished the round.

Cooney became more effective with his left hook in Rounds 3 and 4, mostly to Holmes’s body, and with his left jab, which became an important weapon. Near the end of the fourth, one of Cooney’s left hooks dug deep into Holmes’s right side, and the champion walked slowly back to his corner. In the next round, the men fought evenly. After five rounds, the fight was about even, too, but for the knockdown giving a slight edge to Holmes.

In the sixth, Holmes’s one-two wobbled Cooney again. He rained punches on Cooney until the challenger, ducking to get away, nearly went through the ropes, then righted himself and charged back at Holmes. Just before the bell, Cooney fired off three straight left hooks at Holmes’s body and head, the last one landing flush on the chin. Holmes didn’t flinch, but Cooney was proving that he was a fighter.

By now both men were marked. Cooney’s left eye was cut and starting to close up, and he had cuts along the bridge of his nose. Holmes’s right eye showed some puffiness from the Cooney hooks. The seventh and eighth rounds were closely contested. Holmes was relentlessly economical in his movements, using his jab but also faking it often with a movement of his left arm up and down. Then he’d let it go and follow up with his potent right, a punch he called Big Jack. He was clearly in it for the long haul. Cooney, too, seemed resigned to a long fight—a strategy he would question afterward.

“You gotta rough this guy, Gerry! You’re waiting too long!” Cooney’s trainer, Victor Valle, implored him in the corner. He was right. Cooney didn’t pressure Holmes enough. (Valle’s advice was certainly more useful than Rappaport’s. “America needs you!” the Whacko Twin exhorted his charge.)

Cooney increasingly began landing low blows as the fight wore on. In the ninth, he landed a left hook to Holmes’s groin that made the champion double over. Two points were taken away from Cooney on the scorecards (he had been warned repeatedly). The tenth round was the best of the fight, as Holmes and Cooney fought with a valor and skill that ennobled them both. Holmes seemed largely to get the better of it, but Cooney’s fighting heart was never more in evidence. At the bell both men, exhausted, seemed to tap one another in acknowledgement.

The tenth round seemed to drain Cooney, and he had little left in the 11th and 12th, his jab now a flicker, his left hook a weary swivel. He was penalized a point in the 11th for another low blow. In the 13th, Holmes began teeing off, standing in front of Cooney as he’d rarely done, seeming to understand that the end was near. Cooney had no legs underneath him, and Holmes raked him with right hands. Cooney staggered backward along the ropes, falling to the canvas but hooking the ropes with his right arm and popping back up. The referee began a count, but Valle stormed into the ring and embraced Cooney, stopping the fight. Holmes was the winner and still champion.

The prefight racial friction was replaced by the post-fight discussion about Cooney’s low blows and especially the judges’ scorecards, which after 12 rounds had Holmes ahead 113-111, 113-111, and 115-109. Had Cooney not been penalized three points for low blows, he would have been leading on two of the three cards—not at all the consensus at ringside or elsewhere. As with everything else surrounding the bout, the questions about judging couldn’t avoid speculation about race. How could boxing judges be expected to overlook it, if no one else could? To others, weird scorecards were practically a prerequisite in a big fight, skin color be damned.

But at least the fight itself, at long last, was over.

*******?

Neither man would participate again in an event that captured such universal interest. Holmes would hold the title three more years, his skills slowly eroding, his fights becoming more difficult as he scrapped to retain his cherished title. He could afford to walk away from boxing, but he had a fear of poverty that made him reach for more money whenever it was offered. Besides, his unbeaten record had become a justification in itself; with a few more wins, he could surpass Marciano’s perfect 49-0 mark and make a special mark in boxing history.

At 48-0, Holmes took on light heavyweight champion Michael Spinks, who bulked up and came into the ring at barely 200 pounds. In a stunning upset, Spinks took Holmes’s title by a decision, becoming the first light heavyweight champion to win the heavyweight crown. At the post-fight press conference, Holmes was asked about the late Marciano, some of whose family members were in the room. “Rocky Marciano couldn’t carry my jockstrap,” Holmes said. Like so much of what Holmes said in public, it had the quality of a man speaking beyond any internal editor. It also distorted his true feelings: he had pictures of Marciano in his gym, and he had nothing against the man. But he didn’t want to hear about Marciano, not right now. Everything the American public hadn’t liked about Holmes was crystalized in that moment. Spinks won the rematch on a dubious decision, and Larry Holmes walked away. Then, motivated by the comeback of George Foreman, he returned and fought on for another decade, making still more money. He finally stopped at 52, having driven poverty far from his flowerpots.

Cooney’s brave performance convinced his doubters that he was more than a media creation. But somehow losing to Holmes undid Cooney, who fell into alcohol and drug abuse and never found his way back to the career that was supposed to be his. In the end, the White Hope business scarred Cooney more than Holmes—or maybe it was not so much the burden of representing White America as living up to the expectations of his late (and physically abusive) father, a construction worker who had pushed him into boxing.

“Listen,” Cooney said in a 2003 HBO documentary on the Holmes fight. “I grew up in a house where I learned five things from my old man: ‘You’re no good. You’re a failure. You’re not going to amount to anything. Don’t trust nobody, and don’t tell nobody your business.’ When I lost to Larry Holmes, I felt all five of those things smack me right across the face.” He fought intermittently until 1990 before retiring. Failing to become champion may have been the best thing for Cooney. He kicked drugs and alcohol, married and raised a family, and ran an organization dedicated to helping ex-fighters. Today he hosts a boxing show on satellite radio and does extensive charity work.

Years after the fight, Holmes and Cooney reconciled, and they seem to have developed a genuine friendship. “That’s my buddy,” Holmes said when asked about Cooney in a recent interview. Cooney remembers fondly Holmes’s words just before the bell: “Let’s have a good fight.” Holmes’s gesture never fails to surprise: it is almost as if he were ready to begin the reconciliation before the battle. No one else seemed to notice but Cooney.

Cooney vs. Holmes is remembered today less for the fight than for its climate. Though much of what went on was unsavory, some perspective is in order. Start with the obvious: unlike 1910, there were no race riots and no violence associated with the fight—threats, yes, but no actualities. The media coverage showed bias in favor of Cooney, but it was nothing like what Jack Johnson had faced. Holmes’s victory did not receive the vile denunciations with which newspapers greeted Johnson’s; and Holmes had his defenders. Perhaps the most telling difference was that in 1982, those who sought to make racial appeals for the fight had to deny they were doing so. In 1910, no denials were necessary.

And yet: the bout revealed how America could still see a heavyweight title fight in starkly racial terms. Since 1982 seems far away, it’s tempting to think that such raw racial allegiances wouldn’t prevail today, but this seems like wishful thinking. Racial tension remains present in sports, as elsewhere in American society. Should a promising white American emerge someday in the heavyweight division to challenge a black champion, some sparks would surely fly. But the Cooney-Holmes fight showed that the sparks don’t have to lead to a fire. Even 30 years on, that might be the best we can do.

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

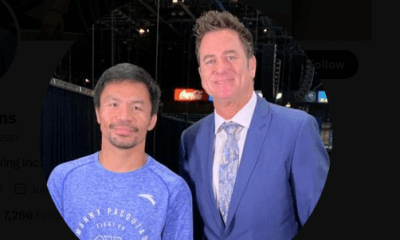

Featured Articles6 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons