Featured Articles

TSS SPECIAL REPORT: What Happened in Texas

As another Texas-sized boxing event approaches with Saul “Canelo” Alvarez vs. Austin Trout, TSS looks back at last year’s middleweight battle between Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. and Andy Lee. Did the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation’s Combative Sports division do their job? Did journalists do any better? Is there anything we can learn from what did (or didn’t) happen last summer in El Paso?

As another Texas-sized boxing event approaches with Saul “Canelo” Alvarez vs. Austin Trout, TSS looks back at last year’s middleweight battle between Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. and Andy Lee. Did the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation’s Combative Sports division do their job? Did journalists do any better? Is there anything we can learn from what did (or didn’t) happen last summer in El Paso?

Last summer, middleweights Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. and Andy Lee agreed to face each other in El Paso, Texas in a 12-round bout for Chavez’s WBC middleweight title belt. The contest would help determine which talented up-and-comer would earn a lucrative opportunity against linear champion and pound-for-pound superstar, Sergio Martinez.

What ended up happening in Texas that summer was more than just a fight. What happened in Texas changed the way I think about the sport of boxing and the journalists who cover it.

The Long and Winding Road

Honestly, at the time of the fight, they were my two favorite middleweights. As a boxing writer in Texas, I had attended Chavez’s two preceding bouts against Peter Manfredo in Houston and Marco Antonio Rubio in San Antonio. It is said that familiarity breeds contempt but that’s a boldfaced lie. The exact opposite is more often the case. Chavez had grown on me.

As for Andy Lee, he’s just one of those fighters who happen to appeal to me for some reason. The Irishman has a pleasant demeanor, is articulate and fights from a southpaw stance; all characteristics I admire. Plus, my personal interaction with him revealed we seem to enjoy the same kind of things: humor, music and movies.

Either man, I thought at the time, would be the one to dethrone the aging Martinez. Still, El Paso is a long way away from Houston, and Texas is not like other states: one does not simply pile into a car to drive to its outermost boundaries. Right?

As it so happened, it actually wasn’t so far outside the realm of possibility to not happen. The McCarson clan, consisting of your TSS scribe and his wife/photographer, Rachel, did decide by unanimous vote that the fight was well worth the 745 mile drive across the long, serpentine highways through lonely parts of Texas. After all, eleven hours in a car is nothing compared to witnessing in person one of the better fights of the year between two of your favorite fighters. Off we went.

Weighty Issues

The customary Friday afternoon weigh-in before the Saturday night bout was anything but normal, despite my report submitted that evening:

Middleweights Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. and Andy Lee both made weight Friday ahead of their scheduled showdown in El Paso, Texas. The bout will be televised live Saturday on HBO World Championship Boxing beginning at 10:00 p.m. ET.

Challenger Andy Lee was first to the scale where officials announced a weight of 159.25 pounds. The usually mild-mannered Lee appeared focused and determined, even going so far as to wear a scowl for the majority of the time he stood on the dais.

Next up was Chavez, who was cheered on heavily by the robust, pro-Mexican crowd of spectators who had waited patiently in line outside the venue to see him before jamming themselves into one of the city’s more famous landmarks, the historic Plaza Theatre.

Chavez, son of legendary Mexican champion of the same name, has developed a reputation as of late for not taking training camps as seriously as perhaps his handlers would like, but he looked fit and ready to rumble this go around, weighing in at 159 pounds.

Both fighters appeared to be in impeccable shape and ready to fight. While fans of Chavez made up the majority of spectators present as expected, there was a noticeable contingent of pro-Lee supporters donning classic gold and black Kronk gym colors there as well.

What’s missing from the report is what I did not see. I did not see the contention on Team Lee’s faces as they argued over the weight of Chavez’s gloves. I did not see them argue with Top Rank officials and trainer Freddie Roach about the construction of Chavez’s gloves, did not see Lee put his own glove on the scale to prove it met the 10 oz middleweight requirement, did not see Texas official Robert Tapia refuse Lee’s request for reasons only he could fathom.

What else did I miss? At 159 pounds, was Chavez “fit and ready” as I noted above? Or was he, as others said at the time, disturbingly gaunt?

A Night at the Bar

A popular song in the Lone Star State says “the stars at night are big and bright, deep in the heart of Texas.” What is said about the night’s sky was also true of the hotel bar that night. For despite being in the relatively secluded area of El Paso, the boxing’s biggest stars were out in full force.

Completed in 1912, this historic Camino Real is a truly magnificent building. The old world spaciousness and attention to detail is a special refuge from what passes for glamour in today’s increasingly postmodernly simple world. Under the cut-glass chandeliers, surrounded by hand-carved marble, said to be carefully crafted by Italian workmen over a century ago, the boxing world got together and had some drinks.

Larry Merchant is knocking them back with fans before turning it in for the night early. Over in the corner, Bob Arum chats with Harold Lederman, each stopping their conversation whenever necessary to submit to passerby requests for pictures or autographs. Irish middleweight Matt Macklin slouches comfortably in a foyer lazy boy, telling all who will listen it will be Lee’s day tomorrow. Peddlers hock shirts and hats with “Chavez” emblazoned across them in red, green and white letters to anyone who will have them. Many will.

Rachel and I are here now, too, over from our quaint Microtel to meet Twitter friends Eoin Casey and Paddy Cronan at the fancy fight hotel. Eoin and Paddy are there when we arrive, chatting it up with boxing trainer Ronnie Shields about tomorrow’s big bout. The Irishmen like Lee’s chances. Shields isn’t so sure, but after a few drinks of our own, Rachel and I do our best to help convince him otherwise.

Suddenly, Jim Lampley enters the fray. Jim snakes his way around the crowd to one of the happy bartenders in the middle of the room to order his fare. He heads back to the elevator when laughter erupts from nearby. It’s our table, because Paddy and Eoin have pointed out something a little peculiar: Lampley isn’t wearing any shoes.

The night ends with more alcohol than it probably should have. Eoin and Paddy are younger than I (at least at heart), so they employ their special Irish brand of vitality to head out and see what other nightlife El Paso has to offer. The McCarsons, meanwhile, put discretion before valor and head back to their sensibly sized mini-sized suite near the airport to rest up for the big fight.

Before drifting off to sleep, I send a direct message to Andy Lee on Twitter. I tell him how excited everyone seems at the hotel and how everyone I talked to believes in him. I do not mention Ronnie Shields, whose concerned look has me questioning my own pick by morning.

Snipers at the Sun Bowl

It almost didn’t happen, in El Paso anyway.

Just two months before the fight, The University of Texas System Chancellor, Francisco G. Cigarroa, forbade the fight from happening at the University of Texas El Paso’s football stadium, the Sun Bowl, citing numerous but vague security concerns. The people of El Paso simply weren’t having it. They wanted a big fight and they would have it. A coordinated effort from the community as well as numerous University of Texas at El Paso officials convinced Cigarroa to reverse his position in short order. Cigarroa's concession came with conditions, though, including the prohibition of alcohol at the event.

Whether warranted or not, Cigarroa’s actions created tons of tension the night of the fight, so much so, in fact, that the Associated Press sent not one, but two reporters to ringside that evening. One of the men there, Bart Barry, was tasked with standard fight report duties. The other, Juan Carlos Llorca, was sent to capture any and all nonboxing events that might occur at the Sun Bowl related to the supposed danger for which Cigarroa was so fearful.

As the sun receded behind the surrounding Franklin mountain range, the threat of rain fell with it. Lined around the top of the stadium’s room, silent guardians appeared as statuesque silhouettes above us, rifles in hand and ready to fire. But Cigarroa was wrong, and Llorca would have nothing to cover that night. Even typical fight night fisticuffs were conspicuously absent this evening. Bout after bout, there was no danger. By the time the main event came, the thought the time spent in the Sun Bowl being anything other than your typical fight night had all but disappeared completely, made only audible every now and then by boxing writer Barry’s teachings to his newly found neophyte friend, Llorca.

It was time for the fight.

The Fight

The fight itself lived up to its billing. It was entertaining and had an abrupt end. The two middleweights accounted well for themselves, each having his moment. Lee got off early, using a sharp, stiff jab and a long reach to build an early points lead. Chavez started coming on though in the fifth, and by the seventh round, his heavier punches were finally taking their toll.

The fight was stopped by referee Laurence Cole at 2:21 of round number seven. Lee was up against the ropes, visibly hurt and unable to defend himself, with Chavez pouring it on top of him like an avalanche.

My ringside report filed at deadline tells the story:

Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. (46-0-1, 32 KOs) notched his most impressive win to date Saturday night in front of 13,467 boxing fans in El Paso, defeating Irish challenger Andy Lee (28-2, 20 KOs) by TKO in round number seven.

Things did not start so well for Chavez.

The fight began with Lee soundly outboxing the tentative Chavez with forceful jabs and deft footwork. The second round was more of the same, as Chavez seemed befuddled by his opponent’s size and reach. In the third, Chavez started finding success digging in hard shots to the body, but he ate too many clean counters from Lee to take the round decisively.

The fourth round went to Chavez, though, as he was able to position Lee in the corner, at times almost at will, and let loose powerful hooks and uppercuts, even stunning the challenger for the first time in the contest when both men landed hard shots at the same time.

It was perhaps then, that Chavez realized the power advantage he possessed over Lee.

The now determined Chavez started taunting Lee in the fifth, which seemed to lead the challenger to not only do the same in return, but to also abandon his jab almost completely in order to trade shots with the slugging Mexican. Both men landed heavy shots as the action picked up.

“He’d just walk through them,” Lee would say afterwards.

The men took turns getting the better of each other in the sixth, with Chavez coming out on top of things by the end of it, landing both excellently timed and powerfully thunderous punches in the corner as the bell sounded.

Chavez would just keep coming in the seventh, where ultimately his harder, more effective blows turned out to be just too much for the brave Irish challenger.

With the win, Chavez retained his WBC middleweight title belt, setting up a showdown with linear champion Sergio Martinez.

After the fight, Lee praised the champion as a worthy opponent for Martinez.

“I couldn’t hold him off,” he said. “He was too big and too strong. He’d give Martinez a hell of a fight.”

Lee’s hall of fame trainer, Emanuel Steward, concurred. “Junior fought a smart fight. He’s very strong. He passed the test. “

After the fight, Chavez seemed confident in the execution of his plan in the fight, despite being down on all three judges scorecards’ at the time four rounds to two.

“I started by studying him,” he said. “I saw he had nothing. I dove in.”

The story of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. is becoming increasingly interesting. The 26-year-old continues to make his mark in the same sport his famous father made his, despite being ever present in the shadow of the man largely considered the greatest Mexican champion of all-time.

“I’m very happy to carry this name, to keep doing more, and to write my story in boxing.”

The next part of the story will include Sergio Martinez. Bob Arum and Lou DiBella confirmed the contest for September 15th in Las Vegas after the fight.

Chavez Sr. seems as eager as his son for the fight. “Martinez has talked too much,” he told the press. “I hope when the times come for the fight he doesn’t’ run like a chicken in the ring.”

Junior was less openly disdainful of Martinez.

“Martinez moves a lot so I’ll have to move. That’s a fight I have to make.”

The fight was over, and it was time to travel home. Plans set beforehand were already in motion. If he ever wanted another shot at the middleweight title, Lee would have to get back in line. For Chavez, his time against Martinez had come. Bob Arum and Lou DiBella were now ready to cash in on the most lucrative fight possible for September’s fast approaching Mexican Independence Day weekend. Everyone was ready to move on.

The story should have been over, but it wasn’t. I did not know it at the time of our long drive home from the furthest point west in Texas, but questions were already starting to circulate within the boxing media. Calls needed to be made; documentation checked. If journalists had failed to ask the right questions in El Paso that night, questions about how PED tests were administered for both fighters, about what PEDs were tested for, about when the tests occurred, someone would now need to pick up the slack to find out what had happened in Texas.

What Andy Lee Didn’t Do

An eleven hour car ride back from El Paso provides lots of quiet time. I spent much of it reflecting on the fight, what Chavez was able to do and what Andy Lee didn’t. First things first, Andy fought a dumb fight.

Andy Lee is a thinking man, a boxer. He’s best when he uses his range, fires off a sturdy jab and keeps his opponent off balance by moving laterally. This does two very important things. First, it keeps his opponent from being able to plant his feet. The less his feet are planted, the less power he can generate, keeping Lee safer from harm. Second, this allows Andy to set up counter shots that have double the impact. As Lee’s opponent moves forward, Lee wants to use his ring generalship to set traps. As his opponent turns and turns to catch him, as he becomes increasingly flustered by Lee’s steady jab, he becomes more and more susceptible to rushing in like a fool. Once he does, Lee can use this ill timed aggression to pounce with naturally hard punches made even more forceful by his opponent’s forward momentum.

When Lee fights like this, he has his best chance to win. When he doesn’t, he risks losing. Such was the case in his first fight against rugged slugger Brian Vera. Vera wanted to make it a brawl and Lee obliged. The result was a TKO 7 upset win for Vera. In his second fight with Vera, though, Lee won virtually every round precisely because he forsook bravado and fought the way he should. The result was a wide UD win for Lee. It was a pure shutout, virtuoso boxer Andy Lee at his best, in such a thorough and sound boxing lesson that Vera had no qualms about serving as Lee’s chief sparring partner for the Chavez fight.

Conventional wisdom said Lee had learned his lesson, but apparently he hadn’t. Because what Andy Lee didn’t do against Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. was fight like he should have. He didn’t learn from his loss and subsequent win versus Brian Vera, didn’t use the time spent with Vera sparring to establish footwork he would use in the fight, didn’t listen to cornerman, the late Manny Steward, telling him not to stand there and trade with Chavez like a glutton.

No, in photos taken that night from ringside, Rachel captured far too many cases of Lee standing right in front of Chavez, far too many moments of the two men’s heads resting up against each other, far too many lineal advances by Chavez met head on by the valiantly foolish Andy Lee.

What Andy Lee didn’t do that night likely cost him the fight.

The Question

Unbeknownst to those of us on press row that evening, there were some serious issues regarding Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr.’s prefight urinalysis.

“The format calls for the fighters to walk to the ring now, but there has been a delay in Julio Cesar Chavez’s dressing room,” Jim Lampley told the HBO television audience. “We’re told that in the other dressing room, Chavez tried and failed to provide a urine sample and the Texas State Athletic Commission has elected to take the sample after the fight.”

But according to Manny Steward and assistant Javon “Sugar” Hill, Chavez submitted his urinalysis before the fight, albeit under less than ideal circumstances.

“A guy runs over into our locker room and tells me to come back over because Chavez has to use the bathroom,” Hill told boxing writer Geoffrey Ciani. “He was taking his gloves off because he had to use the bathroom. So I go back over there, and there is a bathroom in the locker room. He’s in the bathroom and they’re taking his gloves off. That’s the only part I see. I didn’t look in the bathroom to see who was in there, but they took his gloves off when he was in there. There was a guy standing in front and holding a towel up across the doorway of the bathroom, because there was no door. I was standing there for maybe ten minutes at the most. They didn’t tell me he was taking a drug test. They said he had to use the bathroom. I was assuming that he had already taken the drug test because they put the gloves on him the first time.

“Then at that point I go back over there and I’m waiting for him to use the bathroom. Then finally a guy, I don’t know if he was a doctor or not, left. I asked the Commissioner what that was about, and he said, ‘That was Chavez, he just took his drug test’. I said, ‘Chavez just took his drug test now?’ ‘Yeah, yeah. He just took his test right now’.”

So which was it? That was the question (or so it seemed at the time). Did Chavez submit to a urinalysis drug test? Secondarily, did it occur before or after the fight?

Boxing journalists sprang to action, your TSS scribe included. I sent an email to Dickie Cole, Program Manager for Texas’ Combative Sports Program. In what I’ve since discovered is typical Cole fashion, he forwarded my inquiry to someone else for response.

“Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. and Andy Lee submitted urine samples at Saturday's fight,” Public Affairs Project Manager Randy Nesbitt emailed me on June 19, 2012.

“Thanks very much,” I replied. “Can you tell me what company does the testing and when the results are expected?”

No response.

Perhaps Mr. Nesbitt had bigger fish to fry. ESPN’s Dan Rafael (who did not travel to El Paso for the fight) reported later the same day that both Chavez and Lee provided pre-fight urine samples. Rafael’s sources included Billy Keane (Chavez’s manager), Carl Moretti (Vice President of Chavez’s promotional company, Top Rank), and Randy Nesbitt. So then, was HBO’s Jim Lampley just misinformed that evening when he told HBO viewers the urinalysis for Chavez would be done after the fight? Rafael says so. In a pro-Chavez blog entry, the ESPN writer says it was all just misunderstanding.

“Jim's comments at the time were accurate,” said HBO spokesman Kevin Flaherty. “We were unaware that shortly thereafter a sample was provided. That was unfortunate.”

Indeed, “Sugar” Hill’s recollection of the events that night seems to corroborate the story told to Rafael. And, while the circumstances explained by Hill would be less than ideal for any serious urinalysis test (typically, there would only be the fighter and a nonpartisan representative in the room in charge of observing and collecting the specimen), it’s quite within the realm of possibility that the urinalysis test was taken as described.

But were we, as boxing journalists, asking the right question?

The Question about the Question

Let’s assume both fighters took the WBC mandated and Texas prescribed pre-fight urinalysis drug tests just as Rafael reported, and let’s also assume there were no shenanigans done that night to keep either fighter from submitting a valid and true sample. While there seems to be lingering questions about this point, particularly with Chavez, let’s momentarily give everyone the benefit of the doubt and say before the fight, both Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. and Andy Lee submitted pre-fight urinalysis tests in their dressing rooms. Whoever told HBO’s Jim Lampley there was trouble with Chavez submitting his test, and that it would be done after the fight, was simply mistaken. And the events described in the dressing room by “Sugar” Hill were just happenstance. Both fighters took the test. It was administered and collected properly. The tests were sent to the testing agency and the results came back clean.

Is there still a question that hasn’t been asked or answered? Isn’t it readily apparent (in hindsight at least) that we never asked what the urinalysis test we assumed was given was screening for? Perhaps we should have.

As we learned just this February in this TSS exclusive, the state of Texas does not regularly test professional boxers for the use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs), including anabolic steroids, HGH, etc. Instead, the standard nine-panel screen is geared to illicit recreational substances. Moreover, despite numerous inquiries made by TSS, the state will not say definitively whether they’ve ever tested any fighter for PEDs. In fact, the state is even reluctant to advise its main event participants.

Ask Andy Lee. After his loss to Chavez last June, one of his representatives, Damian McCann, personally called Dickie Cole to ask the very questions we in the media should have been asking in the first place.

“He told me his great grandfather or somebody was Irish and we were friends and if there was any wrong-doing he would be the first to put his hands up and fix it in the future,” said McCann. “I got no information at all about events of the previous Saturday evening; he did not know anything about the drug testing.”

McCann says he restated his questions to Cole again via email, hoping Texas’ head boxing man would provide the information. McCann’s email dated 6/18/2012:

Hi Dick,

Good to talk to you earlier. Further to our conversation, I can confirm that Andy Lee provided a urine sample for the Texas State Athletic Commission last Saturday evening (June 16, 2012) before his bout with Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.

I would now like to officially request confirmation and clarity from the Texas State Athletic Commission on the following:

Did Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. provide a urine sample as per professional boxing’s anti-doping drug testing regulations on Saturday evening (June 16, 2012) for the Texas State Athletic Commission?

If so, was Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.’s urine sample test carried out before or after the bout on Saturday evening (June 16, 2012)?

If so, what was the result of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.’s urine sample test of June 16, 2012?

If so, what are the names of the individuals who performed Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.’s urine sample test of June 16, 2012?

Many thanks,

Damian McCann

Cole responded to McCann by forwarding the questions over to – you guessed it – Randy Nesbitt.

Nesbitt again confirmed both Chavez and Lee submitted a pre-fight urinalysis test before their bout, and that the tests would take 7-14 days to be returned. He did not advise McCann on any of his more specific questions regarding the drug tests. McCann remained undeterred. On 6/20/12, he submitted the following:

Mr. Nesbitt,

Further to my request yesterday for a copy of the Texas State Athletic Commission’s Ant-Doping Testing Procedures, Rules and Regulations.

In relation the Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.'s urine sample, can you please advise what specific test(s) are being conducted and what specific drug(s) are being test for?

What are the name (s) of the individual (s) and organisation or laboratory who performed Julio Cesar Chavez Jr.’s urine sample test?

Also can you please advise the name(s) of the official(s) and witness(s) that were present for the test.

Many Thanks,

Damian McCann

Almost three weeks later, McCann finally received a response to his request, though this time from the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation’s Public Information Officer, Susan Stanford and Attorney General Greg Abbot, dated 7/10/12:

Good afternoon, Mr. McCann.

My name is Susan Stanford and I am the public information officer for the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation.

I apologize for the delay in responding to your request but I was out of the office from May 26 until July 2.

I have attached a copy of a Texas Attorney General's opinion regarding the release of information regarding drugs test results in relation to combative sports events. As you can see, the state's AG determined that drug test results constitute confidential medical records and are not public information.

Susan Stanford

Needless to say, TSS’s own subsequent efforts to confirm even the number of fighters tested for PEDs in the state of Texas has been unsuccessful. In fact, it appears the state does not even keep records of the information on hand.

“We do not keep those records,” confirmed Stanford to TSS via phone, when questioned about the unavailability of the records through the Public Information Act.

Aftermath

According to reports, 1.6 million fight fans watched Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr. batter Andy Lee into the ropes on HBO’s World Championship Boxing. The event drew 13,476 people to the Sun Bowl that night and was televised worldwide, producing $1.84 million in ticket sales and distribution revenues for Top Rank, Inc.

Despite its success, questions remain around the drug tests performed that evening. Were any drug tests administered to the participants? Were they done before or after the fight? Were the drugs tests administered in such a way as to ensure both fighters gave accurate and true samples? Perhaps most importantly, in a WBC title bout, a fight between two world-class middleweights, where one of the fighters had previously failed a PED test in Nevada, did the drug test administered include screens for any PEDs, at minimum the diuretic Chavez tested positive for in 2009?

The late Manny Steward remained unconvinced about the situation. His night in El Paso turned out to be his last fight in the corner of longtime friend and roommate, Andy Lee. Steward voiced his concerns to Boxing Scene’s Chris Harmony just three months before succumbing to the illness that ultimately took his life that fall.

“I am very, very surprised and I am very concerned. In my experience I just recently had with Andy Lee; to my knowledge Julio Cesar Chavez [Jr.] never really took any drug test. They me tell me he was going to take a test after the fight and at the last minute they had my nephew come in, ‘Oh, he’s going to take it now’ and here, he comes in the room with two other guys and they said he took the test so he doesn’t have to take nothing now.

“As Andy said, ‘I’ve boxed with Wladimir Klitschko many times; for this fight I boxed with guys 180 pounds. His strength was going like he was almost a 500-pound man’. Based on that and some of the other things I am beginning to see, I realize that there may be something going on that I don’t know of.

“I’m looking at this, and he’s having leg cramps and Manny Pacquiao having leg cramps; there’s too many strange things going on. I really do believe now that’s become a very serious issue in our sport that has to be seriously dealt with, because having advantages of hometowns and small rings, even partial officials, that’s one thing. But to have where a person’s human strength and endurance is doubling and tripling that of an opponent, that could be one of the most difficult and problematic problems in our sport in the next year or so.”

McCann shared similar sentiments to me this week, as we discussed continued efforts to find out what happened in Texas last June. At very minimum, we reason together, the fighters who participated in the main event that night deserve to know what kind of drug tests were ordered, right?

“Emanuel Steward and his assistant, ‘Sugar’ Hill, knew that Andy had to provide a urine sample to officials at the venue prior to the fight,” said McCann. “They or Andy were not aware what drugs would be tested for as there is no uniformed and generic code of practice for drug testing in boxing in the US…but like everyone else we assumed, as a matter of course and to hold in good standing the credibility of the testing practice of [the state], that PEDs would be tested for. Without testing for PEDs, the testing regulations are not fit for purpose and totally inadequate.”

This weekend in San Antonio there will another big time boxing event in Texas. The unification bout between WBC junior middleweight titlist Saul “Canelo” Alvarez and WBA champ Austin Trout will be televised to millions of people all over the world. The venue has already sold over 30k tickets. The promoters of the bout, Golden Boy Promotions, and their television partner Showtime, are sure to bring in millions of dollars in ticket sales and distribution revenues.

What ends up happening in Texas will be more than just a fight. What happens in Texas could change the way we all think about the sport of boxing and the journalists who cover it. Maybe things get better this time. Maybe there will be transparency in the drug testing process, maybe the drug tests will be administered under proper protocol and include a screen for PEDs. Maybe the fighters and the promoters will leave no doubt about what happens in the ring that night and everyone goes home happy. Or maybe things remain the same, or maybe they get worse. Maybe facts about what happens in Texas on fight night keep getting muddled or withheld, maybe PED tests never become the norm, or even enforced, until someone dies in the ring because no one in the state will stand up for the participants.

Follow McCarson on Twitter @KelseyMcCarson.

Featured Articles

Friday Boxing Recaps: Observations on Conlan, Eubank, Bahdi, and David Jimenez

Friday Boxing Recaps: Observations on Conlan, Eubank, Bahdi, and David Jimenez

March 7 was an unusually heavy Friday for professional boxing. The show that warranted the most ink was the all-female card in London, a tour-de-force for the super-talented Lauren Price, but there were important fights on other continents.

Brighton

Michael Conlan, who sat out all of 2024 on the heels of being stopped in three of his previous five, returned to the ring in the British seaside resort city of Brighton in a shake-off-the-rust, 8-rounder against Asad Asif Khan, a 31-year-old Indian from Calcutta making his first appearance in a British ring.

Conlan, a 2016 Olympic silver medalist who famously signed with Top Rank coming out of the amateur ranks, is now 33 years old. Against Khan, he was far from impressive, but did enough to win by a 78-74 score and lock in a match with Spain’s Cristobal Lorente, the European featherweight champion.

Conlan, who improved to 19-3 (9), absorbed a lot of punishment in those three matches that he lost. With his deep amateur background, Michael has a lot of mileage on him and he would have been smart to call it quits after his embarrassingly one-sided defeat to Luis Alberto Lopez. His frayed reflexes speak to something more than ring rust. Heading in, Khan brought a 19-5-1 record but had scored only five wins inside the distance.

Conlan vs Khan was the co-feature. In the main event, Brighton welterweight Harlem Eubank, the cousin of Chris Eubank Jr, improved to 21-0 (9 KOs) with a dominant performance over Conlan’s Belfast homie Tyrone McKenna. Eubank was credited with three knockdowns, all the result of body punches, before referee John Latham had seen enough and pulled the plug at the 2:09 mark of round 10. It was the fourth loss in his last six outings for the 35-year-old McKenna (24-6-1).

Harlem Eubank wants to fight Conor Benn next and says he is willing to wait until after his cousin “wipes Benn out.” Chris Eubank Jr vs Benn is slated for April 26 at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. The North London facility, which has a retractable roof, is the third-largest soccer stadium in England.

Toronto

Local fan favorite Lucas Bahdi and his stablemate Sara Bailey were the headliners on last night’s card at the Great Canadian Casino Resort in Toronto. The event marked the first incursion of Jake Paul’s MVP Promotions into Canada.

Bahdi, who is from Niagara Falls but trains in Toronto, burst out of obscurity in July of last year in Tampa, Florida, with a spectacular one-punch knockout of heavily-hyped Ashton “H2O” Sylva. His next fight, on the undercard of Jake Paul’s match with Mike Tyson, was less “noisy” and the same could be said of his homecoming fight with Ryan James Racaza, an undefeated (15-0) but obscure southpaw from the Philippines who was making his North American debut.

Bahdi vs Racaza was a technical fight that didn’t warm up until Bahdi produced a knockdown in round seven with a sweeping left hook, a glancing blow that appeared to land behind Racaza’s ear. The Filipino was up in a jiff, looking at the referee as if to say, “this dude just hit me with a rabbit punch.”

The judges had it 99-90, 97-92, and 96-93 for the victorious Bahdi (19-0) who was the subject of a recent profile on these pages.

Sara Bailey, a decorated amateur who competed around the world under her maiden name Sara Haghighat Joo and now holds the WBA light flyweight title, successfully defended that trinket with a lopsided decision over Cristina Navarro (6-3), a 35-year-old Spaniard who “earned” this assignment by winning a 6-round decision over an opponent with a 1-4-3 record. The judges scored the monotonous fight 99-91 across the board for Bailey who improved to 6-0 and then returned to the ring to assist her husband in Lucas Bahdi’s corner.

Also

Twenty-two-year-old super bantamweight Angel Barrientes, a Las Vegas-based Hawaii native, delivered the best performance of the night with a one-sided beatdown of Alexander Castellano whose corner mercifully stopped the contest after the seventh round as the ring doctor stood in a neutral corner chatting with the referee.

The gritty Castellano, who hails from Tonawanda, New York, brought an 11-1-2 record and hadn’t previously been stopped. A glutton for punishment, he appeared to suffer a broken orbital bone. Barrientes improved to 13-1 (8 KOs).

The show was marred by an excessive amount of fluffy gobbledygook by the TV talking heads which slowed down the action and made the promotion almost unwatchable.

Cartago, Costa Rica

Fighting in his hometown, super flyweight David Jimenez scored a lopsided 12-round decision over Nicaragua’s Keyvin Lara. The judges had it 120-108, 119-109, and 116-112.

Jimenez, now 17-1, came to the fore in July of 2022 when he upset Ricardo Sandoval in Los Angeles, winning a well-earned majority decision over a 20/1 favorite riding a 16-fight winning streak. That boosted him into a title fight with the formidable Artem Dalakian who saddled him with his lone defeat.

Jimenez’s victory over Lara was his fifth since that setback. It sets up the Costa Rican for another title fight, this time against Argentina’s Fernando Martinez who acquired the WBA 115-pound title in July with an upset of Kazuto Ioka in Japan. Lara, who unsuccessfully challenged Ioka for a belt in 2016, falls to 32-7-1.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Price Conquers Jonas on an All-Female Card at Royal Albert Hall

Ben Shalom’s BOXXER Promotions was at London’s historic Royal Albert Hall tonight with an all-female card topped by a welterweight unification fight between WBC/IBF belt-holder Natasha Jonas and WBA champion Lauren Price.

Liverpool’s Jonas, who turns 41 in June, has had a sterling career, but Father Time has caught up with her. The 30-year-old Price, an Olympic gold medalist, had faster hands, faster feet, and hit harder. The classy Jonas (16-3-1) acknowledged as much in her post-fight interview: “She beat me to the punch every time.”

The scores were 100-90, 98-92, and 98-93.

In advancing her record to 9-0 (2), Price built a strong case that she is the best fighter to come down the pike from Wales since Joe Calzaghe. As for her next bout, she hopes to fight the winner of the March 29 rematch in Las Vegas between Mikaela Mayer and Sandy Ryan. That match, with all of the meaningful welterweight hardware at stake, would be a hot ticket item if potted in Cardiff.

Semi-wind-up

Caroline Dubois staved off a late rally to successfully defend her WBC lightweight title with a majority decision over South Korea’s spunky Bo Mi Re Shin. The judges had it 98-92, 98-93, and 95-95. Although the 95-95 tally by the Korean judge was quite a stretch, Shin performed far better than the odds – Dubois was a consensus 35/1 favorite — portended.

Dubois, a 24-year-old Londoner trained by Shane McGuigan, is the sister of IBF heavyweight title-holder Daniel Dubois. Reportedly 36-3 as an amateur, she advanced her pro record to 11-0-1 (5). Heading in, Shin (18-3-3) had won nine of her previous 10 with the lone setback coming via split decision in a robust fight with Belgium’s Delfine Persoon in Belgium.

Other Bouts of Note

Kariss Artingstall returned to the ring after a 14-month absence and scored a unanimous decision over former amateur rival Raven Chapman. The scores were 98-91, 97-92, 96-93.

The prize for Artingstall, who happens to be Lauren Price’s partner, was the inaugural British female featherweight title and a potential rematch with Skye Nicolson who would relish the chance to avenge her last defeat, a loss by split decision to Attingstall in the quarterfinals of the Tokyo Olympics. Nicolson, who was part of tonight’s broadcast team, defends her title later this month in Sydney against Florida’s Tiara Brown.

It was the first 10-rounder for Artingstall (7-0). Chapman (9-2) had an uphill battle after Artingstall decked her in the second round with a straight left hand.

In a mild upset, Jasmina Zopotoczna, a UK-based Pole, won a split decision over Chloe Watson, adding Watson’s European flyweight title to her own regional trinket. One of the judges favored Watson 97-93, but each of his colleagues had it 96-95 for the Pole. Although there was no great furor, the verdict was unpopular.

Zapotoczna, who fought off her back foot, improved to 9-1. It was the first pro loss for Watson who is trained by Ricky Hatton.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 316: Art of the Deal in Boxing and More

So, they want to save boxing?

A group of guys with recent ties to the sport of boxing and bags of money suddenly believe they can save a sport that is older than any other sport since the dawn of mankind.

Boxing is the oldest sport.

When cavemen roamed the planet, you can believe one tribe bet another tribe their guy could whip the other guy. Thus began the sport of boxing. There was no baseball, soccer or horse racing.

Even the invention of the wheel was still a few generations away when men were duking it out with other men for sport.

Throughout history mentions of one man fighting another man without arms are written in the Tales of Ulysses and other literary references.

Boxing will never die. Period.

Here is the reason why.

Boxing requires only two men in their underwear with no weapons and no requirement of classes in jujitsu, kickboxing, wrestling or advance training facilities. You can prepare in your backyard with one heavy bag and a pair of boxing gloves. It’s simple.

MMA, on the other hand, requires money.

Boxing is for the poor. Any kid can walk into a gym and begin training. When they become adults, then they start paying to use the gym.

Don’t let people fool you and tell you “boxing is dying.”

People have been saying those same words since John L. Sullivan in the late 1800s. You can look it up.

The phrase “boxing is dying,” is said by people who want you to pay them money to save it. Kind of sounds like the guy currently sitting in the White House who is going to save America by firing Americans from their jobs and allowing Russia to take over Ukraine.

Don’t believe these people.

Boxing does not need saving.

Why would Dana White, who has stated for decades that MMA is bigger than boxing, though no MMA fighter can equal the purses of a Saul “Canelo” Alvarez or Tyson Fury, why is he involved in boxing?

There is big money to be made in boxing, especially with internet gambling sites being allowed all over the world. And boxing is popular worldwide. MMA is not.

More people know who Canelo is than UFC’s Alex Pereira.

I respect the UFC fighters. They put in hard work and battle injuries throughout their careers. But MMA is simply not as big as boxing. The purses of MMA fighters at the top level don’t come close to boxing’s top money earners.

Why did Conor McGregor, Nate Diaz and others quickly switch to boxing when called?

The money in boxing is much bigger.

Follow the money.

NYC

A rumble is planned for Times Square in New York City.

Vatos from Southern California are fighting dudes from Nevada and Brooklyn. Sounds like a script from the Gangs of New York.

Where is Leonardo DiCaprio when you need him?

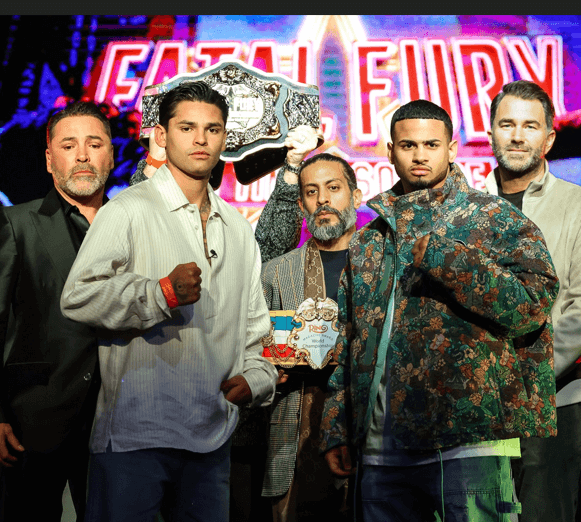

Ryan “KingRy” Garcia (24-1, 20 KOs) will meet Rollie Romero (16-2, 13 KOs) in a welterweight match set for May 2, on Times Square in mid-Manhattan. This is one of three marquee bouts planned to be streamed on DAZN.

Others matched will be Arnold Barboza (32-0, 11 KOs) versus super lightweight titlist Teofimo Lopez (21-1, 13 KOs), and Devin Haney (31-0, 15 KOs) against Jose Carlos Ramirez (29-2, 18 KOs) in a welterweight contest.

This is the proposed match by The Ring magazine backed by Turki Alalshikh who, along with Golden Boy Promotions and Matchroom Boxing, is sponsoring this fight card.

It was also announced that Alalshikh, TKO Group Holdings, and Sela are forming a promotion company.

TKO owns UFC and WWE.

SoCal Fights

Southern California will be busy with boxing cards this weekend.

This Thursday, March 6, is Golden Boy Promotions with a boxing card featuring Manny Flores (19-1, 15 KOs) versus Jorge Leyva (18-3, 13 KOs) in a super bantamweight match at Fantasy Springs Casino. DAZN will stream the boxing card from Indio, California.

On Saturday, March 8, the Fox Theater in Pomona, California hosts a boxing card featuring super middleweights Ruben Cazales (10-0) vs Adam Diu Abdulhamid (18-16). Also, super featherweights Michael Bracamontes (10-2-1) meets Eugene Lagos (16-9-3) at the historic venue promoted by House of Pain Boxing.

On Saturday March 8, Elite Boxing hosts a boxing card at Salesian High in East Los Angeles featuring East L.A. native Merari Vivar (8-0) against Sarah Click (2-8-1) and several other fights.

On Saturday, March 8, an event hosted by House of Champions features top contenders Joet Gonzalez (26-4) vs Arnold Khegai (22-1-1) in a featherweight main event at Thunder Studios in Long Beach, Calif.

A Big All-Female Card in London

On Friday, March 7, the historic Royal Albert Hall in the Kensington borough of London will host an all-female card with two world title fights including a unification fight in the welterweight division.

Natasha Jonas (16-2-1) and Lauren Price (8-0) meet 10 rounds for the IBF, WBC, and WBA belts.

Jonas, 40, the current WBC and IBF titlist, recently defeated Ivana Habazin and before that edged past Mikaela Mayer in a win that could have gone the other way very easily. She will be facing Price, an Olympic gold medalist and current WBA and IBO titlist.

Price, 30, hails from Wales and has an aggressive pressure style that saw her win a battle between punchers with a third-round knockout of Colombia’s Bexcy Mateus this past December in Liverpool. Before that she defeated the always tough Jessica McCaskill.

In the co-main event, lightweights Caroline Dubois (10-0-1) and Bo Mi Re Shin (18-2-3) meet for the WBC world title.

Me Re Shin, 30, fights out of South Korea and has knockout power. She was one of only two fighters to stop Venezuela’s Ana Maria Lozano who has 38 pro fights. That says something. She lost a split decision to Delfine Persoon in Belgium. That really says something.

Dubois had two competitive fights, first, against Jessica Camara that ended in a technical draw due to a clash of heads. Before that she defeated Maira Moneo. Dubois has very good talent and is still young at 24. Is she ready for Mi Re Shin?

Times Square photo credit: JP Yim

Fights to watch:

Thurs., March 6: DAZN, Manny Flores (19-1) vs. Jorge Leyva (18-3)

Fri., March 7: free on DAZN, Lucas Bahdi (18-0) vs. Ryan James Racaza (15-0)

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Madison Square Garden where Keyshawn Davis KO’d Berinchyk

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoLamont Roach holds Tank Davis to a Draw in Brooklyn

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoGreg Haugen (1960-2025) was Tougher than the Toughest Tijuana Taxi Driver

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Hopes to Steal the Show on Friday at Madison Square Garden

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoWith Valentine’s Day on the Horizon, let’s Exhume ex-Boxer ‘Machine Gun’ McGurn

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoGene Hackman’s Involvement in Boxing Went Deeper than that of a Casual Fan

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report — Riyadh Season and Sony Hall: Very Big and Very Small

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Keyshawn Davis at Madison Square Garden