Featured Articles

RIP Tommy Morrison, Who Once Thought He Was Bulletproof

The post-mortem assessments of the boxing career of former WBO heavyweight champion Tommy “The Duke” Morrison – who died late Sunday night in an Omaha, Neb., hospital after a prolonged illness, at the too-young age of 44 — will probably run the gamut of semi-praise (he was very good, but not quite good enough to be truly elite, as also was the case with Gerry Cooney and the late Jerry Quarry) and semi-derogatory (think Duane Bobick and most of the American heavys who have masqueraded as contenders in recent years).

Morrison’s wife, Trisha, whom married him in 2011, was at his bedside when her husband lost his final fight. She said the cause of death was Guillain-Barre Syndrome, not HIV, which Morrison tested positive for in 1996. Other sources indicated it was from respiratory and metabolic acidosis and multiple organ failure.

Truth be told, Morrison was closer to Cooney and Quarry, who very well could have been champions had they come along in a different era (like now), than to, say, Bobick, who had some skills but whose accomplishments never quite measured up to the overly lavish hype that accompanied his meteoric rise, and equally rapid fall. The prevailing view of Bobick now, through the prism of historical perspective, is that he was almost entirely a media creation undeserving of the buzz he created for a brief spell.

Morrison (48-3-1, 42 KOs) captured the vacant WBO version of the heavyweight title by outpointing 44-year-old George Foreman on June 7, 1993, in Las Vegas’ Thomas & Mack Center — admittedly in a bout in which he went against his usual bombs-away philosophy to play hit-and-run with the lumbering but still heavy-handed Big George. Morrison’s critics, and there are many, will also point out that he got hammered in matchups with Lennox Lewis, Ray Mercer and, yes, even Michael Bentt. It’s difficult to imagine even past-their-prime versions of the indisputably great heavyweights being cuffed around quite so soundly as was “The Duke” – a reference to Morrison’s claim to being a distant relative of John Wayne – in those bouts.

But Morrison, who also was notable for his prominent role as “Tommy Gunn” in Rocky V, the fifth and weakest installment in Sylvester Stallone’s iconic movie franchise, also showed flashes of what he was at times, and might have been had his beard been stouter and his lifestyle less reckless. Like basketball superstar Magic Johnson, Morrison had an insatiable appetite for making sexual conquests, many if not all of the unprotected variety, and it led to his career basically ending when it was announced on Feb. 15, 1996, at a press conference in Tulsa, Okla., that he had contracted the HIV virus that leads to AIDS. It should be noted, however, that the first notification of Morrison’s passing did not specifically mention a cause of death.

But, like Magic, who despite his shocking diagnosis and forced retirement from the NBA went on to be a member of the 1992 Olympic gold-medal-winning “Dream Team” in Barcelona, Spain, Morrison never could find peace, prosperity and flashes of glory following his revelation of being HIV-positive. Oh, sure, he did go on to fight three more times – TKO thrashings of Marcus Rhode (in 1996), John Castle (2007) and Matt Weishaar (2008) – while insisting he wasn’t really sick, that the original diagnosis was incorrect and, if it had been when made, he somehow had miraculously “healed” himself. But his actual accomplishments, health and life prospects never approached those of Magic, who today remains a remarkably fit, multimillionaire part-owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Most tragedies-in-the-making, it would seem, really do turn out tragically. Magic Johnson is the apparent exception to that reality, and Tommy Morrison is not, as are the vast majority of life’s designated victims who find that their bodies, no matter how well-maintained, can betray them if the wrong microscopic virus invades a flesh-and-blood host.

But Morrison, at his best, could whack with the best of them. His weapon of choice, as was the case with Joe Frazier and Cooney, was a murderous left hook that could make strong men collapse like a dilapidated building before a wrecking ball. You say he was on the wrong end of one of the most emphatic knockouts ever, his fifth-round blowout by WBO titlist Mercer on Oct. 18 1991, in Atlantic City Boardwalk Hall? Anyone who saw only the highlight-reel footage of that fight’s ending will remember only that, but those who were in the house – and I was at ringside – know that he had unmercifully clubbed Mercer up to the point, late in Round 4, when his gas tank simply emptied. That bout is less an indictment of Morrison’s finishing ability than it is a tribute to Mercer’s ability to soak up punishment like a sponge and still will himself to victory, a quality for which Rocky Marciano, Matthew Saad Muhammad and the late Arturo Gatti are enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Morrison could, at times, be his own worst enemy. He frequently clashed with his exasperated trainer, Tommy Virgets, who never could get his recalcitrant pupil to be as judicious in his behavior outside the ring as, say, a Bernard Hopkins. He went for a quick payday in his Oct. 29, 1993, fight with Bentt in Tulsa, Okla., despite knowing that he was in line for a fat $8 million payday to face Lennox Lewis. Bentt caught the overconfident, underprepared Morrison cold in the first round and stopped him, the date with Lewis sailing out the window. He did wind up mixing it up with Lewis two years later, on Oct. 7, 1995, in Boardwalk Hall, but the time in between did not serve him well, and Lewis starched him in six rounds, flooring him down four times.

But while his occasional stumbles underscore his human frailities, mention should also be made of the fact that Morrison could and frequently did look sensational when he had everything working, like in those first 3½ rounds against Mercer and in winning displays of power in stoppages of Razor Ruddock and Carl “The Truth” Williams.

One is only left to wonder how things would have turned out for Morrison he exercised a bit more restraint in his personal life, which might have adversely affected his performance inside the ropes.

It all went south, and fast, for Morrison on Feb. 10, 1996, the very day he was to have swapped punches with journeyman Arthur “Stormy” Weathers at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, on the undercard of a defense by IBF welterweight champion Felix Trinidad against “Rockin’” Rodney Moore. But the Morrison-Weathers fight was suddenly canceled because of the Nevada State Athletic Commission’s ruling that “The Duke” had been placed on “indefinite medical suspension.” There was immediate speculation — accurate, as it turned out — that the suspension owed to Morrison having tested positive for the HIV virus. At the time, Nevada was one of only three states, Arizona and Washington being the others, that required professional boxers to be tested for HIV.

Five days later, in a crowded hotel meeting room in Tulsa, Morrison confirmed what was already widely suspected. Too many close encounters with female admirers had put him down harder than Lewis or Mercer ever could.

“This is a disease that does not discriminate,” a somber Morrison said as his parents, promoter Tony Holden and Virgets watched with equally long faces. “That’s very, very clear to me now. It doesn’t matter if you live in a drug-infested ghetto in New York City or on a ranch in Jay, Okla. (where Morrison was raised). It can jump up and bite you no matter where you’re at. And I’ll tell you something else. It doesn’t matter what color you are. It doesn’t have a favorite color.

“To all my young fans, I’d ask that you no longer see me as a role model, but as an individual that had the opportunity to be a role model and blew it – blew it with irresponsible, irrational, immature decisions … decisions that one day could cost me my life.

“I thought I was bulletproof. I’m not.”

Virgets told a tale of other opportunities that Morrison faced and, obviously, frequently took advantage of. “I can remember on a number of occasions Tommy doing autograph sessions when there might be 1,000 or 1,200 people go through. At the end, he’d come over and hand me 15 or 20 notes that were handed to him by women. They had names, addresses, phone numbers, little messages that I’d rather not repeat. It was unbelievable.”

Not that any of this hadn’t been forewarned years earlier, as Morrison’s penchant for pleasure-seeking was becoming increasingly obvious. His former promoter, Bill Cayton, said in February 1994 that the fighter “has the physical tools to be the best heavyweight in the world, but he finds it hard to, uh, resist certain temptations.”

Cayton also noted that while Virgets, a no-nonsense sort, had Morrison for two hours of training every day in preparation for an upcoming fight, “Tommy was partying the other 22.”

As it turned out, Morrison’s humbled sense of penitence was short-lived. He wanted back in boxing, and despite being prohibited from fighting in the United States because of the suspension, he wangled a spot on the undercard of a Nov. 3, 1996, show in Chiba, Japan, about 25 miles southeast of Tokyo, headlined by George Foreman’s scheduled 12-rounder against Crawford Grimsley. Foreman won a unanimous decision, while Morrison took out Rhode in one round.

Showtime boxing commentator Bobby Czyz, for one, questioned the wisdom of allowing Morrison to fight anywhere in the world, given his medical situation.

“I know the odds are thousands-to-one against the disease being transmitted in the ring,” Czyz said in September 1996. “But a slight chance is not the same as no chance. Why would anyone want to be in the AIDS lottery?”

For most of the next dozen years after his wipeout of Rhode, Morrison argued that he deserved the opportunity to ply his trade, just as Johnson was allowed to during his brief return to NBA play and in Barcelona. He pointed to his own chiseled 6-2, 225-pound physique as proof that he was no disease-ravaged shell of his former self.

There were those who wanted to believe he was correct in his optimistic self-assessment. Morrison actually was supposed to return to the ring, at 42, in a Feb. 25, 2011, six-rounder against neophyte pro Eric Barrak (3-0, 2 KOs) in Montreal. But the Quebec boxing commission asked Morrison to take still another blood test to ascertain to its satisfaction that Morrison was, as he had so loudly proclaimed, really HIV-free.

“I’m living proof that HIV is a myth,” Morrison had said at the time the bout was scheduled. “All the things that were going to happen, didn’t. Medical mistakes happen all the time and people are misdiagnosed.”

The fact that the Morrison-Barrak fight never came off at least suggests that the results of that other blood test demanded by the Quebec commission did not support Morrison’s claims of a clean bill of health. Morrison’s death just 2 ½ years after his final comeback bid was rejected – and more recent photos of him depict someone who clearly was in physical decline – comprise a sad final chapter of a book that began on such a promising note.

All that can be said is that Morrison’s past appears to finally have caught up with him, and the bright future that should have been his was destined to remain somewhere over the horizon.

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

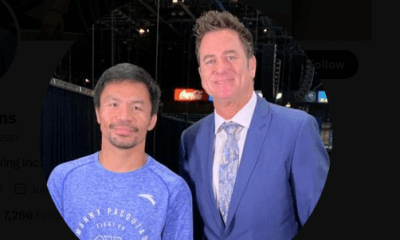

Featured Articles6 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons