Featured Articles

The Heavyweight We Need

One of the best heavyweights in the world climbs the rickety stairs at Main Street Boxing Gym in downtown Houston, Texas on a fair-weathered winter’s day in February. He carries his own bags up the narrow, wooden pathway to the second-story workout room where he intends to wrap his own hands and work out alongside two other fighters who are already up there shadowboxing.

He and the other two men will not speak. They are only connected by their vocations and their movements around the carpeted gym floor. The heavyweight who just entered the room is notieacably larger than the other two fighters. He stands six-feet, three-inches tall and all of it, too. His biceps look like cannonballs, and he appears to have been born for his lot in life.

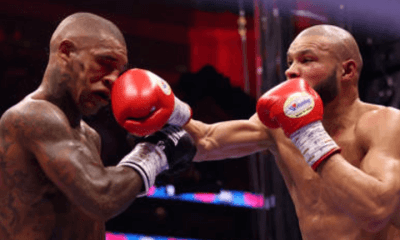

Bryant Jennings (above, in Rachel McCarson photo) is a 30-year-old undefeated heavyweight boxer from Philadelphia. He’s traveled to Houston for his last three fight camps because he feels like it helps him focus on the task ahead of him. He says he loves Philly with a passion but he considers Houston his second home.

“Houston is my go-to spot,” Jennings says as he quietly begins to unravel the necessary amount of tape required to wrap his overly large fists.

Jennings has already been training for a few weeks now. He says he comes to camp earlier than most to get his mind right. He says his primary focus has been developing his fight strategy and focusing his mind on the road that lies ahead.

“I started way ahead of time. It’s nothing strenuous. I’m just walking through a lot of things, getting focused.”

Jennings will be in the fight of his life soon. He faces Wladimir Klitschko on April 25 at Madison Square Garden in New York. Klitschko is one of the better heavyweight champions in history. He has not lost a fight since 2004, almost six years before the late-starting Jennings competed in his very first professional prizefight. Moreover, Klitschko is one of the few men in the world with greater physical dimensions than Jennings. Klitschko is six-feet, six-inches of chiseled heavyweight athleticism and dominance. Even at age 38, it’s seems hardly fathomable that he could be beat. He’s just that good.

Jennings says most of fighting is mental.

“A lot of it is mental. The whole preparation during a training camp and even after the fight is mental. You have to prepare yourself for the next step. That’s why when some people have a loss they have to heal themselves so they can go out and try again. Some people will never heal and that’s when you see their career go downhill. It’s mental all the way around. Life is mental.”

A fighter must tell himself all sorts of things to be ready for fight night. Jennings has convinced himself that most people in the world are against him. He says despite being one of America’s few glimmering hopes in the heavyweight division, people don’t believe in him and don’t want to root for him to succeed.

Whether it’s true or not doesn’t really matter. What does matter is the personal psychology behind it, how Jennings uses the idea to foster his own enthusiasm for training. In short, it fuels him.

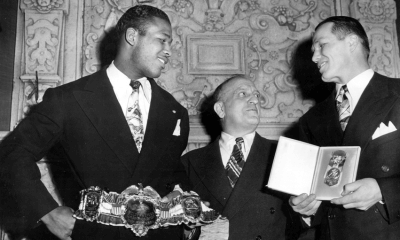

“It’s a very huge moment, and some people don’t even understand it, you know? I’m doubted by a lot of people, whether it’s Klitschko fans or just people who don’t necessarily believe in me, I say listen: this is the opportunity of a lifetime! They don’t understand what’s at stake here? You know? When we mention other names [like] Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier, Larry Holmes, Sonny Liston, Jack Johnson, all these guys were heavyweight champions. And these are guys that are all remembered, guys like Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Lennox Lewis, Wladimir Klitschko, Vitali Klitschko…you get my drift?”

Jennings doesn’t just appreciate history. He wants to make it.

“These guys don’t understand what I’m up against. These are the legacies I’m chasing. My name needs to be amongst all those great heavyweights. So the only way my name can be mentioned alongside those is if I beat Klitschko. Fighting for and winning a vacant heavyweight title doesn’t really hold nothing. My legacy here has a chance to start off by defeating a legend.”

Jennings continues to methodically wrap his hands.

“Why not me?”

Truthfully, it’s an easy question to answer. Klitschko is bigger than Jennings. He’s more skilled. He hits harder. He has one of the best jabs in the history of boxing, and the considerable amount of athleticism he possesses for a man his size makes him extremely hard to beat.

But Jennings won’t hear it.

“I’m a really good athlete as well, and I’m pretty tall. I’m not as tall as him, but my arms are longer so the two or three inches of length on the arms is like what he has me on the height. So it’s almost like the same thing.”

Astoundingly, Jennings is correct. Klitschko’s reach of 81 inches is great, but Jennings’ absurd 84-inch wingspan is even longer, meaning he won’t necessarily be at a disadvantage from the outside against Klitschko by default like most would-be contenders.

“I’m very capable of [boxing him] from the outside.”

Jennings says he’ll put Klitschko through a test he’s never faced before, or at least one he hasn’t taken in an extremely long time. He says when the bell rings on fight night, the reigning heavyweight champion of the world will find himself in the ring with someone who will fight hard the whole night and come on strong as the later rounds approach.

Even better, Jennings promises to deliver action. He admits he has his hands full because Klitschko likes to throw punches from a distance, but also says he’ll bring the fight to him. Klitschko will not have to chase him. Jennings is coming to fight.

“Sooner or later, we’re gonna be fighting. I know the type of punch that he has. I’ve seen it. I’m not going to say I don’t respect it, but I’m in there with him so I’ll have to find a way around it. I ain’t gonna be playing with him, but he ain’t gonna be playing with me. As soon as he feels my power, he’s going to know he’s got to do what he do. He’s going to have to do something.”

Jennings expects to win. He says April 25 will be the inauguration ceremony of his heavyweight championship reign.

“I’m setting myself up to be great. I believed this would happen since the moment I started boxing. I observed the state of the heavyweight division, and I saw what it needed. I just went after it, and right now I think I’m one of the most marketable fighters out there. I’m from America. I’m well spoken, and I’m a heavyweight. It’s what America needs.”

America could stand a few more like him. Outside the ring, he’s intelligent, hardworking, thoughtful and extremely polite. Inside the ring, he’s a highly skilled boxer, a powerful puncher and he’s ready and willing to engage in whatever is necessary to get the job done.

Jennings is on the precipice of becoming the heavyweight champion of the world. There is nothing more important to the health of the sport in America than that. Say what you want about Deontay Wilder winning the WBC title against Berman Stiverne earlier in the year, Jennings is fighting for the lineal heavyweight championship, the real one.

Better yet? He knows it.

“I consider this the real road. I really fought people. This here is the real deal.”

America has pined for a heavyweight to root for since Evander Holyfield fell out of a favor due to old age and eventually retired. Jennings believes he can be the one who brings American heavyweight boxing back. He says it with his dedication to the sport. He says it with his great appreciation of history. He says it with how carefully and thoughtfully he finishes wrapping up his hands before rising to his feet.

I also asked him if he’d be the one.

“For sure,” Jennings says with a smile on his face as he begins this day’s training session in the dark anonymity he chooses for himself in this old, musky gym in Houston. Soon, he’s drifted away from us. He’s punching air inside the boxing ring with a faraway look in his eye. He’s not chasing ghosts. He’s prepping for the real thing.

The writer and the photographer leave him there. He is alone with his thoughts now. His focus is singular and superb. Jennings wants to defeat Klitschko for the world heavyweight championship. He’s dreamed about it his whole fighting life. It isn’t just another payday. It isn’t just another fight. He needs it.

Maybe we do, too.

Featured Articles

Boxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

In recent years, there has been lavish praise and extensive criticism regarding Turki Alalshikh’s boxing initiative. Some of it has been warranted and some hasn’t. One issue deserves greater comment.

The judging has been pretty good.

Scoring a fight is subjective, which can open the door to bias, incompetence, and corruption.

Most people in boxing know who the good judges are. But some bad ones keep getting high-profile assignments. Why? Because they shade things toward the house fighter which is where the money lies.

When there’s a bad decision in boxing, almost always it favors the house fighter.

Overall, Turki Alalshikh’s fights have been marked by honest scoring.

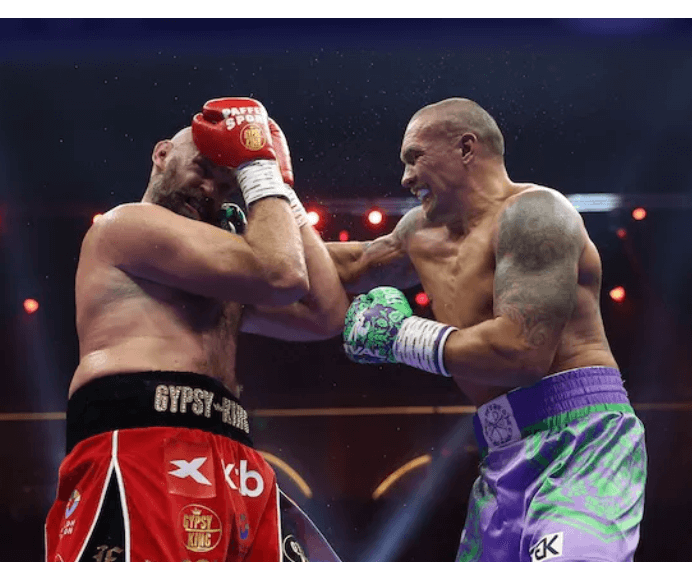

Oleksandr Usyk went the distance four times against Tyson Fury and Anthony Joshua. Fury-Usyk I and Usyk-Joshua II could legitimately have been scored either way. It was in the Saudi’s financial interest (not to mention the interests of Frank Warren and Eddie Hearn) that Fury and Joshua win those fights. Yet Usyk won all four decisions.

Clearly, Turki Alalshikh wanted Hamzah Sheeraz to defeat Carlos Adames. Yet Adames retained his title when that bout was credibly scored a draw.

The list goes on.

Bad scoring trickles down from the top. Judges know that the monied interests behind a promotion want a certain fighter to win and that their receiving lucrative judging assignments in the future often depends on scoring the fight at hand a certain way.

The judging for Turki Alalshikh’s fights so far seems to have been based on the instruction, “Be fair. Get it right.”

Kudos for that.

****

Six years ago after unifying the four major cruiserweight titles, Oleksandr Usyk was honored by the Boxing Writers Association of America as its “Fighter of the Year.” That designation was repeated in 2024 in recognition of his unifying the heavyweight crown.

While in New York to accept his most recent honor, Usyk sat with former NFL MVP Boomer Esiason for an interview that will air in early-June on the nationally syndicated television show Game Time.

Oleksandr came across as thoughtful and likeable during the conversation.

He shared memories of his father: “My father was a military guy. He teach me like a street fight, to work a knife, shooting. I use jujitsu, karate, wrestling, kickboxing. I say, ‘Poppa, what we do this for?’ . . . He says, ‘We prepare’ . . . ‘For what we prepare?’ . . . ‘For life.’”

Usyk won a gold medal in the 201-pound heavyweight division at the 2012 London Olympics. But his father died before Oleksandr could return home and show the medal to him. After Usyk beat Tyson Fury to unify the heavyweight crown, he cried as he proclaimed, “Hey, poppa, we did it.”

“A lot of people in Ukraine who hear that, they cry too,” Oleksandr told Esiason. “Is normal. [Some] people, ‘Hey man! Don’t cry.’ Why not cry? I like to cry.”

Speaking of the size differential between Fury and himself, Usyk noted, “For me, is like a story. David and Goliath. I not afraid because boxing is a sport. Yeah, it’s a guy a little bigger for me. No problem.”

Asked how he would describe his fighting style,” Oleksandr answered, “It’s a wonderful style.”

“Boxing for me is a gentleman’s sport,” he added. “Just respect for my opponents. A lot of people make a show. But if you make a good show and then bad boxing – [with a wave of his hand] PFFFTHF! First in boxing is class and skill; then the show.’

He explained how his training regimen includes holding his breath underwater: “I make like a fight time. Three minutes underwater, one minute rest, twelve rounds. Is hard.”

What’s the longest that Usyk has held his breath underwater?

“My record is 4 minutes 47 seconds.”

The interview closed with Oleksandr appealing directly to the American people to support his Ukrainian homeland in its defense against Russian aggression.

“I’m not political. I’m just [a] man who lives in Ukraine who’s worried for my people.”

And he talked of having brought some Ukrainian soldiers to his fights as guests: “They’re my power, my angels.”

****

Don King has been the subject of an endless stream of anecdotes. Jody Heaps (who spent three decades as a senior creative director and executive producer at Showtime) adds one more to the mix.

“Don had just brought Mike Tyson to Showtime,” Heaps recalls. “We were doing a shoot with Don sitting in a barber chair and he was in a great mood. Toward the end, someone came over to me and said, ‘If Don has the time, could you ask him about his favorite movie scene for a promotion we’re doing.’ So I asked Don what his favorite movie scene was. He told me movies weren’t his thing and said, ‘You tell me. What’s my favorite scene?’

“I talked it over with the crew,” Heaps continues. “Then I suggested the shower scene in Psycho. I figured Don had seen it. Everybody has seen it. But Don told me, ‘I don’t know anything about it. What happens in that scene?’ So I explained that you see Janet Leigh in shower. Then you see a silhouette on the shower curtain. The shower curtain is pulled aside. You see the knife plunging in again and again. And the last thing you see is blood circling down the drain.”

“Don says, ‘Okay; I’ve got it.’ He looks right at the camera and, with incredible drama, starts recreating the scene. Five seconds in, everyone is mesmerized. He takes us through Janet Leigh in the shower, the silhouette on the shower curtain, the knife plunging in again and again, the blood circling down the drain. And at the end, he laughed that loud booming laugh of his and proclaimed, ‘It was a clean kill!’

“There was stunned silence,” Heaps says in closing. “Don made it sound like it was real and he’d been there when it happened.”

****

Like most sports fans, I watched the first round of the NFL draft on April 24. I’ll do the same when the NBA draft is held on June 25. Allow me the following thoughts.

Adam Silver seems like a basketball fan.

Roger Goodell seems like a fan of making money.

Adam Silver looks sincere when he hugs a draftee.

Roger Goodell looks like he wants to take a shower.

Adam Silver comes across as though he has a sense of humor and can laugh at himself.

Roger Goodell comes across as though he doesn’t and can’t.

Adam Silver has James Dolan to deal with and keeps him in line.

Roger Goodell can’t put a lid on Jerry Jones.

Adam Silver is booed in good-natured fashion by fans at the draft.

Roger Goodell is booed with rabid enthusiasm

****

And last; a memory of Turki Alalshikh’s May 2 fight card in Times Square . . .

Security was tight. The police had been instructed to keep pedestrians on the sidewalk moving as they passed the ring enclosure which was blocked from view by a ten-foot-tall fence. Well before the event began, a young man with a video camera planted himself on the sidewalk across the street from the enclosure. A uniformed police officer approached and the following colloquy occurred.

Cop: I’m sorry, sir. You’ll have to move.

Young man: I’m with the media.

Cop: And I’m with the New York Police Department. You’ll have to move.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His next book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing – will be published this month and is available for preorder at: https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Hiruta, Bohachuk, and Trinidad Win at the Commerce Casino

Hiruta, Bohachuk, and Trinidad Win at the Commerce Casino

A jam-packed fight card featuring a world champion, top contenders and knockout artists delivered the action but no knockouts on Saturday in the Los Angeles area.

You can’t have everything.

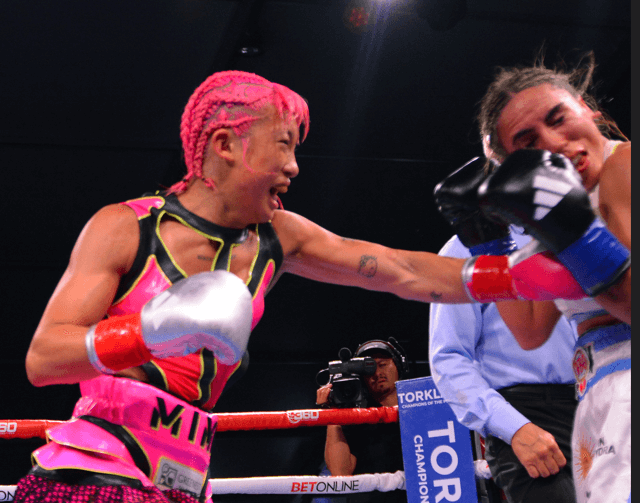

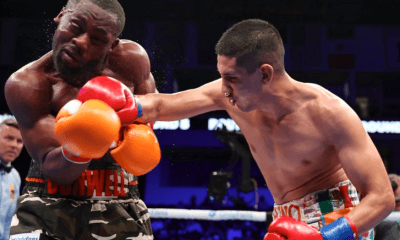

Mizuki “Mimi” Hiruta (8-0, 2 KOs), fresh with a multi-year 360 Boxing Promotion’s contract deal, once again fought and defended the WBO super fly world title and this time against Argentina’s Carla Merino (16-3, 5 KOs) at Commerce Casino.

It was expected to be her toughest test.

Hiruta, who is trained and managed by Manny Robles, showed added poise and a sharp jab that created and established an invisible barrier that Merino could never crack. It was as simple as that.

A sharp right jab from the southpaw Japanese world champion in the opening round gave Merino something to figure out. When the Argentine fighter tried to counter Hiruta was out of range. That distance was a problem that Merino could not solve.

The pink-flame-haired Hiruta looks like an anime figure incapable of violence. But whenever Merino dared unload a combination Hiruta would eagerly pounce on the opportunity. It was clear that the champion’s speed and power was a problem.

For more than a year Hiruta has been training in Southern California and has sparred with numerous styles and situations in the talent-crazy Southern California area. Each time she fights the poise and polish gained from working with a variety of talent and skill partners seems to add more layers to the Japanese fighter’s arsenal.

After six rounds of clear control by Hiruta, the Argentine fighter finally made an assertive move to change the momentum with combination punching. Both exchanged but Hiruta cornered Merino and opened up with a seven-punch barrage.

In the eighth round Merino tried again to force an exchange and again Hiruta opened up with a three-punch combo followed by a four-punch combo. Merino dived inside the attack by the Japanese champion and accidentally butted Hiruta’s head. No serious damage appeared.

Merino tried valiantly to exchange with Hiruta but the strength, speed and agility were too much to overcome in the last two rounds of the fight. Left hand blows by the champion connected solidly several times in the final round.

After 10 rounds all three judges saw Hiruta the winner by decision 98-92 twice and 99-91. The fighter from Tokyo retains the WBO super fly title for the fourth time.

Bohachuk Wins

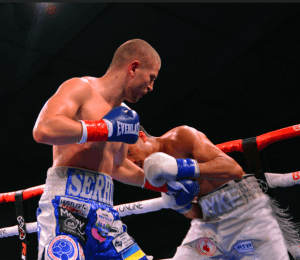

Ukraine’s Serhii Bohachuk (26-2, 24 KOs) defeated Mykal Fox (24-5, 5 KOs) by unanimous decision but had problems corralling the much taller fighter after 10 rounds in a super welterweight match.

It was only the second time Bohachuk won by decision.

Fox used movement all 10 rounds that never allowed Bohachuk to plant his feet to deliver his vaunted power. But though Fox had moments, they were not enough to offset the power shots that did land. Two judges scored it 97-93 for the Ukrainian and another had it 98-92

“Good experience for me,” said Bohachuk of Fox’s movement.

King of LA

In a super featherweight match Omar “King of LA” Trinidad (19-0-1, 13 KOs) dominated Nicaragua’s Alexander Espinoza (23-7-3, 8 KOs) but never came close to knocking out the spirited fighter. But did come close to dropping him.

The fighter out of the Boyle Heights area in the boxing hotbed of East L.A. was able to exchange freely with savage uppercuts to the body and head, but Espinoza would not quit. For 10 rounds Trinidad battered away at Espinoza but a knockout win was not possible.

After 10 rounds all three judges favored Trinidad (100-90, 99-91, 98-92) who retains his regional WBC title and his place in the featherweight rankings.

“I’m living the dream,” said Trinidad.

Maywood Fighter Medina on Target

Lupe Medina (10-0, 2 KOs) proved ready for the elite in knocking down world title challenger Maria Santizo (12-6, 6 KOs) and winning by unanimous decision after eight rounds in a minimumweight match up.

Medina, a model-looking fighter out of Maywood, Calif, accepted a match against Santizo who had fought three times against world titlists including L.A. great Seniesa Estrada. She looked perfectly in her element.

Behind a ramrod jab and solid defense, Medina avoided the big swinging Santizo’s punches while countering accurately. For every home run swing by the Guatemalan fighter Medina would connect with a sharp right or left.

In the fifth round, Santizo opened up with a crisp three-punch combination and Medina opened up with her own four-punch blast that seemed to wobble the veteran fighter. Medina stepped on the gas and fired strategic blows but never left herself open for counters.

Medina didn’t waste time in the sixth round. A crisp one-two staggered Santizo who reeled backward. The referee ruled it a knockdown and Santizo was in trouble. Medina went into attack mode as Santizo pulled every trick she knew to keep from being overrun by the Maywood fighter.

In the last two rounds Medina seemed to look for the perfect shot to end the fight. Santizo kept busy with short shots and stayed away from meaningful exchanges. Medina also might have been gassed from expending so many punches in the prior round.

The two female fighters both seemed to want a knockout in the eighth round. Santizo was wary of Medina’s power and dived in close to smother Medina’s firing zone. Neither woman was able to connect with any significant shots.

After eight rounds all three judges scored in favor of Medina 77-74, 76-75 and 80-71.

It was proof Medina belongs among the top minimumweight fighters.

Other Bouts

In a super welterweight fight Michael Meyers (7-2) defeated Eduardo Diaz (9-4) by unanimous decision in a tough scrap. Mayers proved to be more accurate and was able to withstand a late rally by Diaz.

Abel Mejia (8-0) defeated Antonio Dunton El (6-4-2) by decision after six rounds in a super feather match.

Jocelyn Camarillo (4-0) won by split decision after four rounds versus Qianyue Zhao (0-2) in a light flyweight bout.

Photos credit: Al Applerose

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

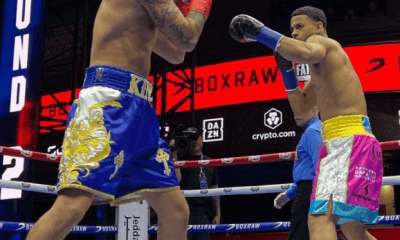

David Allen Bursts Johnny Fisher’s Bubble at the Copper Box

The first meeting between Johnny Fisher, the Romford Bull, and David Allen, the White Rhino, was an inelegant affair that produced an unpopular decision. Allen put Fisher on the canvas in the fifth frame and dominated the second half of the fight, but two of the judges thought that Fisher nicked it, allowing the “Bull” to keep his undefeated record. That match was staged last December in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, underneath Usyk-Fury II.

The 26-year-old Fisher, who has a fervent following, was chalked a 13/5 favorite for the sequel today at London’s Copper Box Arena. At the weigh-in, Allen, who carried 265 pounds, looked as if he had been training at the neighborhood pub.

Through the first four rounds, Fisher fought cautiously, holding tight to his game plan. He worked his jab effectively and it appeared as if the match would go the full “10” with the Romford man winning a comfortable decision. However, in the waning moments of round five, he was a goner, left splattered on the canvas.

This was Fisher’s second trip to the mat. With 30 seconds remaining in the fifth, Allen put him on the deck with a clubbing right hand. Fisher got up swaying on unsteady legs, but referee Marcus McDonnell let the match continue. The coup-de-gras was a crunching left hook.

Fisher, who was 13-0 with 11 KOs heading in, went down face first with his arms extended. The towel flew in from his corner, but that was superfluous. He was out before he hit the canvas.

A high-class journeyman, the 33-year-old David Allen improved to 24-7-2 with his 16th knockout. He promised fireworks – “going toe-to-toe, that’s just the way I’m wired” – and delivered the goods.

Other Bouts of Note

Northampton middleweight Kieron Conway added the BBBofC strap to his existing Commonwealth belt with a fourth-round stoppage of Welsh southpaw Gerome Warburton. It was the third win inside the distance in his last four outings for Conway who improved to 23-3-1 (7 KOs).

Conway trapped Warburton (15-2-2) in a corner, hurt him with a body punch, and followed up with a barrage that forced the referee to intervene as Warburton’s corner tossed in the white flag of surrender. The official time was 1:26 of round four. Warburton’s previous fight was a 6-rounder vs. an opponent who was 8-72-4.

In the penultimate fight on the card, George Liddard, the so-called “Billericay Bomber,” earned a date with Kieron Conway by dismantling Bristol’s Aaron Sutton who was on the canvas three times before his corner pulled him out in the final minute of the fifth frame.

The 22-year-old Liddard (12-0, 7 KOs) was a consensus 12/1 favorite over Sutton who brought a 19-1 record but against tepid opposition. His last three opponents were a combined 16-50-5 at the time that he fought them.

Also

In a bout that wasn’t part of the ESPN slate, Johnny Fisher stablemate John Hedges, a tall cruiserweight, won a comprehensive 10-round decision over Liverpool’s Nathan Quarless. The scores were 99-92, 98-92, and 97-93.

Purportedly 40-4 as an amateur, Hedges advanced his pro ledger to 11-0 (3). It was the second loss in 15 starts for the feather-fisted Quarless, a nephew of 1980s heavyweight gatekeeper Noel Quarless.

Photo credit: Mark Robinson / Matchroom

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

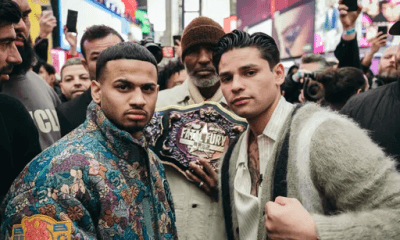

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 324: Ryan Garcia Leads Three Days in May Battles

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia