Featured Articles

Eddie Futch Tribute – Trainer Extaordinaire

Eddie Futch Tribute – Any “best-of” list is, of course, subjective. Whenever someone offers his or her opinion on such, it almost always makes for lively and sometimes heated debate. Boxing is no different; if you make the case that Sugar Ray Robinson is the greatest fighter of all time, be prepared to argue the point with contrarians who are just as staunch in their belief that Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong, Willie Pep or Harry Greb deserves to be celebrated as No. 1. More recent devotees to the sweet science will nominate Floyd Mayweather Jr. for the top spot and, if they don’t, Floyd himself will.

It’s no different when the topic shifts slightly to discussion of who should be recognized as the greatest trainer ever. The list of renowned chief seconds without question is impressively deep. Contenders for designation as best of the best include such legendary corner strategists as Ray Arcel, Emanuel Steward, Charlie Goldman, Whitey Bimstein, Gil Clancy, Jack Blackburn, Cus D’Amato, Nacho Beristain, Angelo Dundee and George Benton, just to name a few. All have been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Non-Participant category.

As the winner of an unprecedented seven Trainer of the Year awards from the Boxing Writers Association of America, Freddie Roach certainly deserves to be considered for the mythical status as the GOAT among trainers. But if you ask Roach — who presently is in the Philippines preparing Manny Pacquiao for his Nov. 5 challenge of WBO welterweight champion Jessie Vargas at Las Vegas’ Thomas & Mack Center — as to the identity of the true king of the hill among trainers, he said it’s an open-and-shut case. The late, great Eddie Futch, for whom the BWAA Award is now named, stands alone, according to Roach, and is likely to remain out front until the end of time.

“Eddie was a great trainer, a great teacher, but he was even better as a person,” Roach, himself an inductee into the IBHOF (2012), told me in a 2 a.m. telephone call (my time) from the Philippines. “When I went to work for him after I retired (as an active boxer), that was the best move I ever made in my life. I’m so happy I did.

“He really taught me the ins and outs of boxing. We cut no corners and worked our asses off the whole way. That’s why the fighters we had were great. He made sure their work habits were unbelievable. Here I am getting ready for another title fight with my best fighter, Manny Pacquiao, and he’s looking better than ever because I’m taking him back to my Eddie Futch days.”

Eddie Futch’s days were many, and almost uniformly glorious. He was 90 when he passed away on Oct. 10, 2001, having continued to train fighters until he was 86. Right to the end of his career and even his life, Mr. Futch never seemed to lose anything off his proverbial fastball; his memories of long-ago fights and fighters were richly detailed and he could call them up with WiFi speed. More than a few boxing writers, when asking about his remembrances about some of the fighters he instructed – a Who’s Who compilation that included, at one time or another, such notables as Joe Frazier, Ken Norton, Larry Holmes, Michael Spinks, Alexis Arguello, Bob Foster, Riddick Bowe, Holman Williams, Virgil Hill, Mike McCallum, Marlon Starling and his very first champion, Don Jordan – were astounded that he could describe in detail not only particular rounds from decades earlier, but punch sequences during those rounds.

But near-total recall without perspective and foresight is essentially a squandered gift. Where “Mr. Eddie,” as he was reverentially known by his many admirers, excelled was his ability to put his breadth of knowledge into the sort of useful context that enabled his fighters to attain maximum efficiency on fight night.

“I think Eddie’s greatest asset was to build a game plan for a particular fight,” Roach said. “He was the absolute best at getting his guy ready to beat a certain opponent. Everyone remembers how he got Frazier, in what was his best performance, prepared to beat Muhammad Ali in their first fight. He did it with Norton, too. He did it with a lot of fighters.”

What is especially amazing is not only that Futch was such an exquisite strategist, but he could get his message across without ever seeming to raise his voice or to resort to the sort of expletives that are so common in a sport where expletives are as much a part of the terminology as nouns and verbs. Futch was unfailingly courteous and polite, but his genteel manner masked an inner strength his fighters quickly came to understand and respect. When he spoke, his quiet, measured comments were not so much a suggestion as a command, leaving little or no room for dissent. What else would you expect of someone who could quote verbatim from the works of his favorite 19th-century British poets, and whose bearing was as professorial as it was professional?

“Beautiful man, beautiful man,” Benton, who died on Sept. 19, 2011, said of Futch in Corner Men: Great Boxing Trainers, authored by Ronald K. Fried in 1991. “We never had a disagreement about anything because I knew that he was knowledgable about what he was doing. And he knew that I was the type of guy who was knowledgable about what I was doing – but I was still learning all the time, getting that experience with him.

“I would way the biggest thing I picked up from him was psychology. Eddie is a real psychologist when it comes to human beings. He knows what to say to you and how precisely to say it to you. That’s why he gets along with guys. It’s easy to teach when you’re this way, because every human being is not the same. They don’t think the same.”

Futch’s understated way was never more evident than in Ali-Frazier I on March 8, 1971, perhaps the most-anticipated boxing match ever. With Madison Square Garden a madhouse of emotion, Mr. Eddie was the calm eye of the hurricane, telling Smokin’ Joe to fight with fury but under control, and not to stray from the tactically brilliant plan he had outlined beforehand.

It is, of course, true that not every pupil of an outstanding teacher is able to instruct in the same way and with the same results. When it came time for Joe Frazier to train fighters, including his son, heavyweight prospect Marvis Frazier, Smokin’ Joe taught them all to fight exactly as he had, bobbing and weaving constantly forward and firing left hooks, often to their detriment. Frazier was indisputably a greater fighter than Roach and Benton, but some of the lessons Futch tried to pass along to his proteges were grasped more readily by some than by others.

Noting that many trainers scream at their fighters in order to be heard as noise and tension levels in arenas rise, Roach said that Futch was the quintessential embodiment of “grace under pressure,” which is how the celebrated author Ernest Hemingway defined courage.

“Eddie was never loud in the corner because he didn’t need to be,” Roach said. “He understood that a lot of yelling only confuses fighters. What Eddie was able to do in that minute between rounds was so important. That’s when you have to tell your guy what he needs to do in the next round in order to help him win the fight. If you’re overly excited, the fighter gets overly excited and the game plan starts to fall apart. What happens then? You’re lost. Eddie taught me that the quiet way is the best way.”

Born in Hillsboro, Miss., on Aug. 9, 1911, Futch moved to Detroit with his family when he was five. Years later, at the Brewster Recreation Center in the early 1930s, he frequently sparred with Joe Louis, despite giving away 50-plus pounds, because Louis wanted someone smart and swift to help sharpen his reflexes. By all accounts, even the great “Brown Bomber” never was able to consistently catch up with the nimble and observant Futch, who was learning as much from those sessions as Louis was from him.

Futch, a lightweight, was 37-3 as an amateur and won the 1933 Detroit Golden Gloves championship, but a physical examination revealed that he had a heart murmur shortly before he was to turn pro in 1936. He thus was obliged to shift his attention from fighting to the training of fighters, but it was hardly an easy or a seamless transition. There were bills to pay, after all, and Futch made ends meet by holding a variety of jobs unrelated to his passion, boxing. At various times he worked as a hotel waiter, road laborer, welder and distribution clerk for the main branch of the Los Angeles Post Office. It was his speed and accuracy at sorting mail that mirrored his finest traits as a trainer.

In Dave Anderson’s 1991 book, In the Corner: Great Trainers Talk About Their Art, Futch described his proficiency thusly:

“I think Texas had 737 cities and towns then. Big cities like Dallas and Amarillo were the distribution points for all the little towns. But no matter how well you knew where the towns were you had to take a test every year. You had eight minutes to throw 100 cards in the right cubicle. You had to get 95 percent correct. I did it in three minutes and I always got 100 percent.”

But for all that he did well, and without a lot of chest-thumping, Futch was not without his disappointments. Sometimes his fighters didn’t listen as closely as they might have, and sometimes, if things didn’t work out as well as planned, they required a scapegoat. In boxing, the trainer is always the most convenient target for assigning blame. Frazier, Holmes and Arguello were just three of the fighters who at one time or another disappointed Futch by turning away from him, although in more instances than not they regretted any rifts that were caused and apologized to him.

Futch was enough of a realist to understand how the game is played, and he wasn’t the kind to let grudges fester. But forgiving and forgetting are not always one and the same, as he told Fried.

“I’m in (boxing), but I don’t like a lot of things in it,” he said. “I tolerate some things because that’s the way it is. Ingratitude is one of them. The ones I’ve done the most for have been the ones who have been the most ungrateful.”

Eddie Futch would be 106 now, had he lived long enough to hit triple digits. When he was still an active boxer Roach admits to occasionally disregarding his mentor’s sage dictums, acts of impetuosity which continue to nag at him. But Roach is enjoying his own second act, as the foremost preacher of the gospel according to Eddie, and he vows that some of the mistakes he made back in the day will not be repeated in the here and now.

“I’m so fond of my fighter here in the Philippines,” Roach said, referring to Pacquiao. “We’ve been together 15 years now, me and Manny. He’s lost a couple of times here and there. Maybe it was my fault, maybe it wasn’t. But he’s stuck with me for those 15 years. Most marriages don’t last that long these days.

“I’ve got a real loyal guy, and that’s how I was with Eddie. If I didn’t listen to him sometimes, I would end up losing the fight. But he always got me back on track. He’d take the time to explain to me what I did wrong and what I should have done instead. It made perfect sense to me then, and it makes perfect sense to me now.”

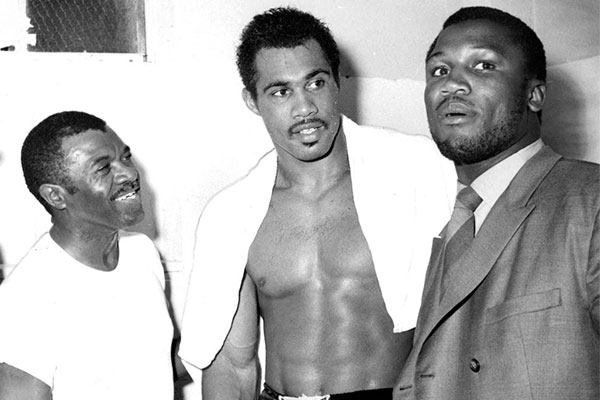

Pictured: Eddie Futch with ken Norton and Joe Frazier.

Eddie Futch Tribute / Check out more boxing news and videos at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision