Featured Articles

Honoring Cecilia Braekhus Isn’t ‘Politically Correct,’ It’s just the Right Thing

Cecilia Braekhus, receives the initial Christy Martin Award from the award’s namesake this Friday night at the 93rd annual Boxing Writers Association of America

Until I decided to take a stand for women’s boxing, or more precisely for the right of women to box if that is what they choose to do, no one had ever accused me of being “politically correct.” I’m pretty sure that, on the whole, I am far from being a PC type of person. But you don’t have to conveniently fit into someone else’s stereotype to adhere to the principles by which we profess to live our lives. When the “First Lady,” Cecilia Braekhus, receives the initial Christy Martin Award from the award’s namesake this Friday night at the 93rd annual Boxing Writers Association of America Awards Dinner in New York City, I’d like to think far more people than not will also consider it to be the right thing.

History gets made in ways both great and small, and the BWAA’s collective decision to break with tradition and create a Female Fighter of the Year award was not made hastily. It was proposed two years ago, with some members of the organization understandably cautious about taking what must have seemed a bold and possibly controversial step. As the former president of the BWAA and still its awards chairman, I championed that step being taken, as did current BWAA president Joseph Santoliquito and BWAA members David A. Avila, of The Sweet Science, and Tom Gerbasi, both of whom write extensively about women’s boxing.

The blue-ribbon committee that was formed to select the first such honoree did its job well; the 36-year-old Braekhus, who was born in Colombia and adopted as a toddler by a Norwegian family, performed splendidly in 2017, winning three bouts against quality opponents. She made more history last weekend, becoming the first featured female boxer in HBO’s 45-year involvement in the sport when she scored a 10-round unanimous decision over Kali Reis in Carson, Calif., to extend her record to 33-0 and retain her fully unified welterweight championship. Although the figurative glass ceiling for female boxers hasn’t exactly been shattered, Braekhus and women such as Claressa Shields and Ireland’s Katie Taylor have at least served to crack it a bit.

We all evolve as we grow and what we thought yesterday might not be exactly what we think today, or tomorrow. But being a son, husband and father of two daughters has served to convince me – and, really, this has little to do with politics and religion, although those hot-button topics touch all of us to some degree or another – that the women in our extraordinary country deserve no less consideration in virtually all aspects of their daily existence than is expected by their male counterparts. Equal pay for equal work, regardless of gender, would seem to be an indisputable concept in 21st century America. There is absolutely no justification for a woman receiving 77 cents for every dollar a man receives for doing the same job, and especially so if she has similar experience and qualifications.

There are exceptions to any rule, however, and the sports world is rife with them. Thanks to the crusading efforts of Billie Jean King and others, Serena Williams can now earn as much for winning major tournaments as the men do. Professional tennis, however, is an outlier. No matter how dominant Braekhus is in the ring, she can never hope to be paid as handsomely or receive the same level of global recognition as elite male fighters. It is a matter of supply and especially demand, driven by a marketplace that gives only so much credence to the concept of gender equity. It’s the same thing in women’s basketball, where the best of the best in the WNBA, players such as Candace Parker, Diana Taurasi, Maya Moore and Sylvia Fowles, earn tiny fractions of what comparable players in the NBA receive. The average wage for WNBA players is around $75,000, and Parker is one of only six women whose skill and popularity is such that during the 2017 season they received the max of $113,500. Compare that to the NBA’s average salary of $6,517,428, or the Powerball Lottery payouts to megastars Steph Curry ($34.7 million) and LeBron James ($33.3 million). With endorsements, James augments his enormous NBA salary by an annual average of $52 million while Curry pulls down an additional $42 million. Even 55-year-old Michael Jordan, who hasn’t played in the NBA since 2003, pocketed more endorsement money in 2014 than he made from the teams that employed him during the entirety of his 15-year playing career.

The yawning gap between the benefits that had long gone to male athletes, in comparison to women, began to close somewhat at the amateur level with the passage by Congress of Title IX in 1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in any educational program or activity receiving any type of federal financial aid. Just like that, colleges receiving such aid were required to provide equal opportunities for female athletes, which resulted in vastly increased funding, or even the creation programs for women’s basketball, soccer, swimming, tennis, golf and volleyball.

Where I differed with Title IX’s hard-line feminists was their unreasonable (to my way of thinking) resistance to allowing scholarship exceptions for college football. Since football at such schools as Alabama, Ohio State, Michigan, Texas and, yes, my college, LSU, were so profitable that the game basically funded all or most of the new or expanded women’s sports benefiting from Title IX, I believed the mandate to provide equal numbers of athletic grants-in-aid for men and women should have excluded football. That argument was shot down, however, resulting in the unfortunate elimination of several men’s sports such as wrestling, gymnastics and even baseball at some schools, a draconian measure instituted in order to make the numbers fit.

No one was ever going to confuse legendary Alabama football coach Paul “Bear” Bryant as a feminist, but he was first and foremost a realist. Prior to the passage of Title IX, Bryant was of the opinion that it really didn’t matter if female cheerleaders for the Crimson Tide could do nifty tumbling routines or form human pyramids, but darn, they had better be drop-dead gorgeous. If that sounds sexist, well, it probably was. But when Title IX maneuvered him into a position he never wanted to be in, the Bear said in that growly, Chesterfield-tinged voice, and I’m paraphrasing here, “I don’t much care for girls’ sports, but if they’re gonna have `Alabama’ on the front of their uniforms they had better win.’”

Forty-six years after Title IX improved conditions for female student-athletes, some of the battles of the past are still being waged in the sordid era of Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein and Larry Nassar (the long-time doctor for the USA women’s gymnastics team convicted of sexually abusing dozens of young girls). There is no quick fix for all of society’s ills regarding the entrenched degradation of women, but with Mother’s Day fast approaching each male among us should take a moment to consider what kind of gesture we can make to honor those who gave us life. If I took even a small step in that direction by acknowledging the hard work and sacrifices made by women who wanted nothing more than to test themselves in an area previously reserved only for the guys, I’m fine with that. I’d like to think my late mom, who always said she was the fastest girl at her school and might have excelled in track had she been encouraged to do so and had an avenue through which to demonstrate her talent, celestially approves of whatever minor role I had in the creation of the Christy Martin Award.

It isn’t the first time that women’s boxing and I have intersected in a manner I hardly could have anticipated. After Muhammad Ali’s daughter, Laila Ali, made her pro debut with a perfunctory one-round blowout of a moonlighting Denny’s waitress named April Fowler on Oct. 8, 1999, I called Joe Frazier’s daughter, Philadelphia attorney Jacqui Frazier-Lyde, to get her opinion of the daughter of her father’s fiercest rival taking up her celebrated pop’s trade.

“If I trained to do it, I could kick her ass,” Frazier-Lyde, a star basketball player at American University, responded. After a moment of hesitation, she added, “As a matter of fact, I think I will kick her ass.” Shortly thereafter Frazier-Lyde began training at her dad’s gym, and on June 8, 2001, she and Ali squared off Verona, N.Y., in what was optimistically hyped as “Ali-Frazier IV.” Media from around the nation and the world showed up for the event, which Frazier-Lyde loudly and frequently proclaimed was happening because of the question I had posed to her nearly two years earlier. At least three of my male colleagues, who clearly weren’t in attendance of their own volition, came over and essentially grumbled, “So you’re the one responsible for this crap.”

Ali defeated Frazier-Lyde on an eight-round majority decision in a competitive and entertaining bout, for which they were each paid more money than any women’s boxer had ever made to that point. Of course, that largely owed to the kind of name recognition no female boxer before or since has enjoyed. While women’s boxing slipped back into a fallow period after headliners like the celebrity daughters, Martin and Lucia Rijker retired, at least a seed had been planted. It bloomed into inclusion as an Olympic sport in 2012, helping make instant stars of Shields and Taylor.

The ladies have clawed and scratched for everything they’ve achieved during this latest revival. Having served in the Marine Corps, this curmudgeonly non-PC type still opposes the notion of women as combat troops, but there can be no denying that Braekhus is a national heroine in Norway and Shields is a two-time Olympic gold medalist for the USA who might soon be paired against Christina Hammer in a fight that might turn out to be bigger than Laila-Jacqui.

The train is still building momentum, but it’s coming through and those who would defiantly oppose its even being on the track run the risk of being flattened. If you don’t care to watch, then don’t. But for any American to suggest that women shouldn’t even have an opportunity to chase their boxing dreams seems antithetical in a country that from its inception has espoused the right to freedom of expression and the pursuit of happiness.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

For more on female boxing, visit our sister site THE PRIZEFIGHTERS

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

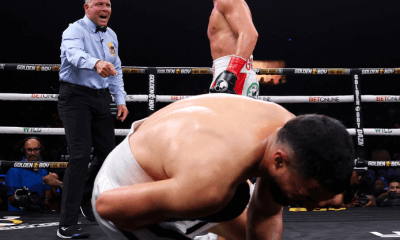

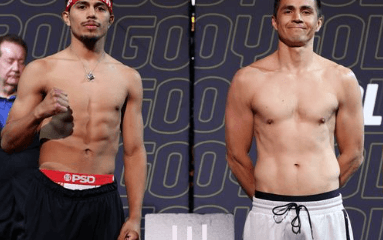

Featured Articles6 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

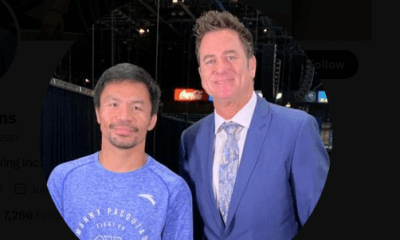

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons