Featured Articles

Don’t Be Blue! The Met Philly is a Great Fight Town’s New (Yet Old) Boxing Venue

Bernard Hopkins, the renowned former middleweight and light heavyweight champion from Philadelphia, once explained his compulsion for adding layers to his boxing legacy by noting that “history is forever.”

Well, sometimes it is. But history, while seldom if ever completely vanishing, can fade with the passage of time. Which is not to say adjustments to what once was can’t be made; in a remarkable trade-off, one chapter in the regal boxing history of B-Hop’s hometown is permanently slamming shut while another just a few blocks away on North Broad Street is about to be rewritten for a new generation and possibly succeeding ones. It is as if Sir Isaac Newton’s third law of physics – “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction” – is being played out in real life.

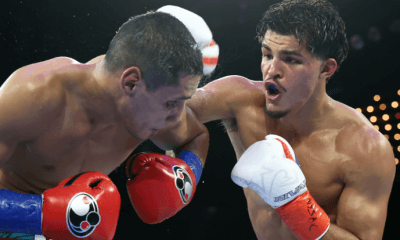

Goodbye forever, iconic fight club Blue Horizon. Hello, Metropolitan Opera House, or as it is now known, The Met Philadelphia, again pristine and gorgeous after a $56 million transformation over the past 18 months. The first of what is being promised as regularly scheduled boxing events at The Met takes place this Saturday night with an 11-bout card, the headliner an eight-rounder pitting undefeated local prospects Jeremy Cuevas (11-0, 8 KOs) against Steven Ortiz (9-0, 3 KOs), for the vacant Pennsylvania lightweight championship. It is a nostalgic nod toward the neighborhood turf wars that once fed the city’s reputation as an incubator of hard-as-nails fighters who made their bones by slugging it out with one another.

Other matchups of interest have Samuel Teah (15-2-1, 7 KOs), of Northeast Philly by way of his native Liberia, going against Tre’Sean Wiggins (10-4-1, 6 KOs), of Johnstown, Pa., in an eight-rounder for the vacant Pennsylvania junior welterweight belt; welterweight Malik Hawkins (13-0, 9 KOs), of Baltimore, swapping punches with Gledwin Ortiz (6-2, 5 KOs), of the Bronx, N.Y., in an eight-rounder, and junior welter Branden Pizarro (13-1, 6 KOs), of the Juniata Park section of Philly, taking on Zack Ramsey (8-5, 4 KOs), of Springfield, Mass., in a six-rounder.

“The place is definitely beautiful. Breathtaking,” Cuevas, 23, a North Philadelphia native now residing in South Philly, said after a tour of The Met on Tuesday. “Who wouldn’t want to fight in such a beautiful venue in his hometown? I’ve always wanted to be involved in something like this, and now I’m here. It really hasn’t sunk in yet. But I have to win. Do that and what’s already a special occasion becomes a little more so.

“The hype is astounding, as it should be. I have a chance to help bring it all back to Philly, and to do it in style.”

Manny Rivera, president of Philadelphia-based Hard Hitting Promotions, is excited about the prospect of a long and mutually beneficial partnership with Live Nation Philadelphia, a company whose primary business is concert promotion and whose list of recording artists is topped by popular Philly rapper Meek Mill. Although Saturday’s fight card is the launch of The Met Philly’s reincarnation as a boxing venue, the facility, which first opened in 1908 and hosted boxing events from 1934 to 1954, has been operational since Dec. 3, when 77-year-old folk-rock legend Bob Dylan prophetically ushered in a new yet somehow familiar era by performing many of his hits that dated back to the 1960s, as did the majority of his audience.

Maybe what goes around really does come back around again, if someone with the will and the finances is determined to make it so.

Rivera said Hard Hitting Promotions expects to stage six fight cards at The Met in 2019, the next on a yet-unspecified date in April, “and go on from there,” adding layers onto the next-phase legacy of an again-grand facility that had fallen into disrepair and might have been marked for demolition were it not been for the intervention of Geoff Gordon, regional president of Live Nation Philadelphia, who saw the potential of the crumbling old palace and was willing to back his vision of a glorious future with a massive financial infusion.

“It’s an exciting opportunity for boxing and we have a wonderful spot to watch competitive boxing on North Broad Street,” Gordon said of the restored, multi-purpose Met, whose 858 North Broad Street address is just five blocks below the site once occupied by the Blue Horizon at the 1314-16 North Broad. But the Blue Horizon (as it had been known since 1961, so dubbed by fight promoter and then-owner Jimmy Toppi), which was constructed in 1865, hadn’t staged a fight card since June 4, 2010, when featherweight Coy Evans scored a six-round unanimous decision over Barbaro Zepeda in the main event. Almost immediately thereafter, Philadelphia’s Department of Licenses and Inspection again cited the Blue for electrical code violations, among other things, and co-owners Vernoca Michael and Carol Ray, unable to pay for necessary repairs and mounting tax bills, were obliged to shutter the building until the debt rose to a point where they had no alternative but to sell.

Historical preservationists – hey, it’s Philadelphia, where tens of thousands of tourists come annually to check out Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell and other 18th-century monuments to a significant period in America’s past – argued that it was imperative to prevent the Blue Horizon from decaying to the point where it might be unsalvageable. Boxing aficionados were also at the forefront of the ultimately failed crusade, noting that The Ring magazine had declared the 1,346-seat Blue as the very best place in the world to watch boxing, while an article in Sports Illustrated contended it was the “last great boxing venue in the country.” But those tributes were ultimately negated by pragmatic politicians who argued that while the Blue was indeed historic, it wasn’t “historic enough” for another governmental bailout after the facility had received a $1 million grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as well as a $1 million low-cost loan from the Delaware River Port Authority.

Although Michael and Ray, African-American women who had quit their jobs and gone $500,000 into debt to purchase the building, used the funds to make several cosmetic touch-ups, Michael complained that the Blue was “in continual need of repair” and they would require another $5 million in grants or private contributions to make enough renovations to bring it up to code. The people controlling the purse strings in Philly and Harrisburg said thanks but no thanks, which is why the Marriott hotel chain is sinking more than $25 million into the former Blue Horizon site, which is being transformed into a 140-room micro-hotel as part of the chain’s new Moxy brand, which a press release promises will “bring a lifestyle experience to a new level.”

Maybe that indeed will be the case, but you have to wonder if the ghosts of Bennie Briscoe, Matthew Saad Muhammad and other beloved and departed Philly fighters who learned to ply their brutal trade at the Blue will wander the corridors of the Moxy like restless spirits on an endless flight.

The Met Philadelphia – at least in its original incarnation – is in its own way just as rich in boxing history as the Blue Horizon. Built in 1908 by Oscar Hammerstein, it started out as the home of the Philadelphia Opera Company. Toppi, who later owned the Blue Horizon, began staging regular fight cards there in the 1930s, during which time the Cuban great, Kid Gavilan (a record eight appearances), Lew Jenkins, Percy Bassett and George Costner were among the headliners. And, unlike the “not historic enough” (at least in some people’s estimation) Blue, The Met has been certified by the Philadelphia Historic Commission by its listing on both the Pennsylvania State and National Registers of Historic Places.

Perhaps of most significance to fight fans, The Met’s configuration for boxing should make for a rewarding viewing experience. With a seating capacity of 4,000 or so for concerts, 800 floor seats will be removed on boxing nights for placement of the ring, which will be surrounded on three sides by curved rows of seats, all of which will offer splendid sight lines, with additional seating on the elevated stage. Rivera said he anticipates a turnout of 2,500 to 3,000 spectators.

“This building is like the Blue Horizon 5.0,” gushed Rivera, who points out that, unlike the Blue, The Met offers patrons multiple and modern concession stands and rest rooms.

All that remains is for The Met to live up to its obvious potential as a fight site that fans will want to keep returning to, which has not been the case with several one-and-done venues that were tried out as replacement or augmentary alternatives to the Blue. Other Philly boxing sites that were more than suitable for the purpose and for a time found their niche were allowed to slip away for whatever reason, victims by turn of progress or abandonment.

So say goodbye not only to the Blue, but to Sesquicentennial/Municipal Stadium, site of the first Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney heavyweight title bout on Sept. 23, 1926, which drew a crowd of 120,757, and Rocky Marciano’s dethronement of heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott on Sept. 23, 1952 (attendance: 40,379), and to the Spectrum, home to so many well-attended fights in the 1970s, which was demolished from Nov. 2010 to May 2011. Say goodbye also to Convention Hall, the Pennsylvania Hall at the Civic Center (demolished in 2005), the Cambria (affectionately known as the “Bucket of Blood,” closed in 1963); the Arena in West Philly, the Hotel Philadelphia in Center City, the Alhambra, Olympia, Broadway Athletic Club and National Athletic Club (all in South Philly) and Eli’s Pier 34 along the Delaware River waterfront. Less-entrenched in Philly’s boxing culture, in some cases still standing but seldom if ever still utilized as boxing venues, are Poor Henry’s Brewery in Northern Liberties, the National Guard Armory in Northeast Philly, Woodhaven Centre, Felton Supper Club, Wagner’s Ballroom and the University of the Arts.

It should be pointed out that The Met is not and will not be the sole destination for boxing in Philadelphia moving forward. There is the Liacouras Center on the Temple University campus, which on March 15 will be the site for an IBF junior lightweight defense by champion Tevin Farmer (28-4-1, 6 KOs), of North Philly, against Ireland’s Jono Carroll (16-0-1, 3 KOs), as well as a women’s lightweight unification matchup of IBF/WBA ruler Katie Taylor (12-0, 5 KOs) of Ireland and WBO titlist Rose Volante (14-0, 8 KOs)) of Brazil. Fifteen days later at the 2300 Arena in South Philly, the converted warehouse (capacity: 2,000) which has undergone a number of name changes (among them Viking Hall and the New Alhambra), it’ll be WBC light heavyweight champion Oleksandr Gvozdyk (16-0, 13 KOs), of Ukraine, defending his belt against Doudou Ngumbu (38-8, 14 KOs), of Congo. There also are periodic cards at the SugarHouse Casino, with a nice but small room that can accommodate maybe 1,100 fans.

Hall of Fame promoter J Russell Peltz, who has been staging fight cards in Philadelphia since 1969, is still going strong at 72 and he welcomes the addition of The Met as a local outlet for boxing and hustling promoters, such as Rivera, to provide the sort of competition that can only make for an improved overall product. He got a peek inside The Met during its restoration and said it represents a long step toward a Philly pugilistic rebirth, but it will take more than spiffy new digs to bring the glory days all the way back.

“It’s all good if the fights are good,” said Peltz, who is co-promoting the two world championship cards in March. “If the fights aren’t good, the site won’t matter quite as much. It all depends on the quality of the fights.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision