Featured Articles

Holmes-Spinks I: The Grassy Knoll for Boxing’s Conspiracy Theorists

The most enduring of American conspiracy theories involves a gunman who may or may not have existed and may or may not have been on a grassy knoll in Dallas’ Dealey Plaza the afternoon of Nov. 22, 1963. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the subject of numerous speculative books and movies, all of which involve some individual’s ironclad take on what happened, why it happened and who was involved in making it happen, will always be grist for the mill for those still dissecting that national tragedy. More than a few of those arguments dispute the Warren Commission’s official conclusion that presumed killer Lee Harvey Oswald acted on his own and not in concert with unidentified, shadowy figures.

On a more recent and lesser scale, a raft of conspiracy theories arose in the wake of the alleged Aug. 10 jailhouse suicide of multimillionaire sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, whose list of celebrity acquaintances includes two presidents of the United States and even a member of the British royal family. As was the case when nightclub owner Jack Ruby fatally shot Oswald before he could go on trial, conspiracy theorists on all sides have conjectured whether Epstein’s suspicious death was actually a hit and, if so, ordered by whom?

Boxing, with its blemished past dotted by nefarious power brokers and decisions that sometimes defy logic, also has provided conspiracy junkies with ample material to analyze and debate. Olympic boxing, often characterized as a cesspool of corruption, immediately comes to mind. So does the Sept. 10, 1993, majority draw in which WBC welterweight champion Pernell Whitaker, whom almost everyone without an official scorecard saw as the clear victor, was obliged to settle for a dissatisfying standoff with crowd favorite and Mexican national hero Julio Cesar Chavez in a bout that drew a live crowd of 60,000 or so in the Alamodome in San Antonio, Texas. Although Whitaker retained his title on the draw, he and his outraged supporters were convinced the outcome was predicated more on the WBC, headquartered in Mexico City, exerting behind-the-scenes influence to ensure that Chavez came away with his undefeated record still intact. Irrefutable truth is often difficult to pin down in such matters, but the 55-year-old “Sweet Pea,” who died after being struck by a car on July 14, went to his grave believing he had been cheated out of a deserved triumph that would have further embellished his Hall of Fame legacy.

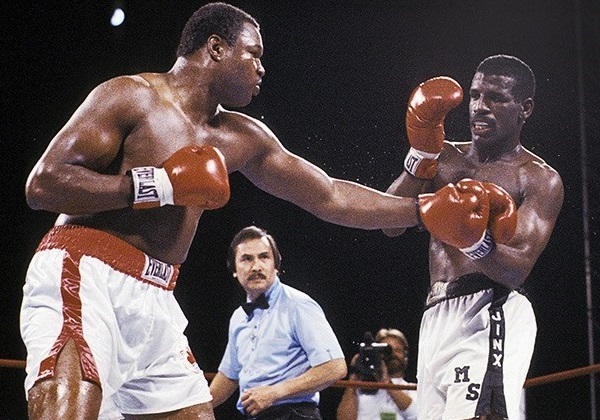

Given its historical implications, what is arguably the grassy knoll of boxing remains the Sept. 21, 1985, pairing of long-reigning heavyweight champion Larry Holmes and undisputed light heavyweight titlist Michael Spinks, who was attempting to become the first (or maybe not) 175-pound champ to move up in weight and capture his sport’s most prestigious and lucrative prize.

Spinks – who came away with a razor-thin and controversial 15-round unanimous decision — was bidding to do something no other light heavyweight had ever done, although there are those who cite Tommy Burns, who outpointed heavyweight champ Marvin Hart over 20 rounds on Feb. 23, 2006, as the first 175-pound titlist to accomplish the feat. In any case, since Burns, 13 light heavyweight champs had tried and failed in their bids to become king of the heavyweights, a list that included such ring legends as Billy Conn, Archie Moore and Bob Foster.

Given the fact that the 35-year-old Holmes was making his 20th title defense and was widely considered as one of the best heavyweight champions of all time, he was installed as a prohibitive favorite over Spinks, who was not only bucking tradition but the perceived limits of his own body. Even respected Los Angeles Times sports columnist Jim Murray, noting that Spinks had weighed in at 199¾ pounds – heavier than such legendary heavyweight champions as and Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano ever did for title bouts – went a bit overboard in writing that the challenger looked “like a blowfish” and that his weight gain was accelerated by a 4,500-calorie-a-day diet that might be “all right for a guy getting ready to play Henry the Eighth.”

But Spinks’ bulking-up process was not the result of having scarfed down a bunch of French fries, chocolate milkshakes and doughnuts, but rather the calculated machinations of New Orleans-based fitness coach and nutritionist Mackie Shilstone, whose then-unorthodox methods would soon gain wider acceptance but then were seen by the boxing establishment as, well, somewhat bizarre.

“We have a scientific, unique program that is secret – a program that was developed specifically for Michael, using techniques that would be revolutionary for boxing,” Shilstone said to the bemusement of hidebound traditionalists.

Spinks, whose walking-around weight between light heavyweight matches was usually 10 pounds or so above the division limit, said he was already familiar working with Shilstone – to shed unwanted pounds.

“Mackie had already helped me lose weight to get down to light heavyweight,” Spinks said when contacted for this story. “He told me that if I wanted to fight Larry Holmes for the heavyweight championship, he could help me put the weight on the right way. And that’s what he did. He also said he wouldn’t take anything from what I already had, in terms of what I did well as a light heavyweight, that I still would be able to do all that as a heavyweight. He was right, too. I was as fast as a heavyweight as I was as a light heavyweight.”

Unlike Conn, Moore, Foster and other light heavyweight champs who made no secret of their ambition to storm and conquer the heavyweight division, Michael admits to initially lacking the burning desire to replicate the feat of his older brother and fellow 1976 Olympic gold medalist Leon Spinks, who dethroned WBC/WBA heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali via 15-round split decision in a monumental upset on Feb. 15, 1978. Leon had always been naturally larger than Michael, never weighing less than 194 pounds for any of his first 23 outings as a pro. The mere notion of moving up to heavyweight seemed unlikely and more than a bit risky to Michael, who figured he would continue to do what he’d already been doing, which was to dominate all comers at light heavy.

It was Butch Lewis, who promoted both Spinks brothers, who determined that Michael going to heavyweight was not only doable, but highly advisable financially.

“Butch told me I could fight Larry Holmes for the heavyweight championship,” the younger Spinks recalled. “I was, like, `What?’ He said, ‘Yeah, and you can beat him.’ I said, `You really think so?’ And he said, `Absolutely.’

“Butch (who was 65 when he died of a heart attack on July 23, 2011) had faith in me, so I took that and ran with it.”

Maybe what bottom-line Butch had was absolute faith in the economic realities of boxing, which always hold that heavyweight champions are vastly better-compensated than their light heavyweight counterparts. Consider these numbers: Michael Spinks’ purse for his final light heavyweight defense, an eighth-round stoppage of Jim MacDonald on June 6, 1985, was a relatively paltry $100,000, a pittance compared to the $1.1 million contract he signed to challenge Holmes.

Say what you will about the flamboyant Lewis, who was noted for wearing a tuxedo and bow tie but no shirt on fight night, but his steering of Michael Spinks’ career was a case study on how to milk the system for every available dollar. It was Lewis who made the bold call, after Spinks had followed up his stunner over Holmes by outpointing the “Easton Assassin” on another close and controversial call, a 15-round split decision in the rematch seven months later, to hold Spinks out of the heavyweight unification tournament being put together by HBO Sports president Seth Abraham and promoter Don King. In doing so Spinks passed on a potential $5 million payday against eventual tourney winner Mike Tyson, but he was paid about the same amount to defeat the formidable Gerry Cooney, putting into motion a series of events that led to his June 27, 1988, megafight with Tyson in Atlantic City. OK, so Spinks didn’t make it through the first round, but he received a career-high $13.2 million for what proved to be his final fight and only professional loss, a pretty nice parting gift when you get right down to it.

Holmes had his own potential date with destiny in that first clash with Michael Spinks. Were he to win, it would be his 49th consecutive victory without a loss, matching the record set by Marciano – ironically, against Archie Moore and, even more ironically, 30 years to the day after The Rock knocked out the Ol’ Mongoose in the ninth round in what turned out to be his final fight.

In the lead-up to the fight at The Riviera in Las Vegas, for which members of the Marciano family were invited guests, Holmes seemed to chafe at constantly being compared to a beloved fighter who had died in a crash of a small private plane on Aug. 31, 1969. “I’m not fighting Marciano,” Holmes complained. “He’s dead. I never knew him. I’m fighting for Larry Holmes, for me, for what I can do for my family.”

To Holmes, who was no stranger to the seven-figure club and who was down for a $3 million purse, there was a racial component to the constant comparisons to Marciano, who was white, much in the same manner that black baseball great Hank Aaron was the target of unfair and sometimes cruel criticism as he neared the sacrosanct record of 714 career home runs set by Babe Ruth. When Aaron passed Ruth by homering for the 715th time on April 8, 1974, the feat was celebrated by many Americans and baseball fans in general, but not by everyone.

Members of the Marciano family, who ostensibly had been summoned to congratulate Holmes in the event of his making it to 49-0, celebrated when the close decision for Spinks – by margins of 143-142 (twice) and 145-142 – was announced. That did not set well with Holmes, who felt such a display was disrespectful to him and, additionally, was the wrong call historically as long-reigning champions such as himself usually got the benefit of the doubt in close fights.

“I was robbed,” Holmes, in announcing one of his several retirements from boxing that didn’t stick, said at the postfight press conference, suggesting that alleged conspirators in influential places who finally had brought him down can “kiss me where the sun never shines,” which meant “my big black behind.”

Nor was Holmes any more disposed to be gracious to Peter Marciano, Rocky’s younger brother and the foremost keeper of the “Brockton Blockbuster’s” eternal flame. “You are freeloading off your dead brother,” Holmes told Peter, tossing in the zinger that “Rocky couldn’t carry my jockstrap.”

Months later, after the heat of the moment had long since cooled down, Holmes, in most instances a respectful and thoroughly decent man, offered a public apology to anyone he might have offended with his earlier intemperate remarks.

“I’m sorry for what I said, for the way things came out,” Holmes told a Boston reporter. “I don’t want to take anything away from Peter or the Marciano family. I haven’t slept for two months thinking about this.

“I’ve reached out to Peter Marciano. I’d like to get together with him, either in his town or mine (Easton, Pa.). There must be something that can be done to make this right.

“I have no hard feelings against Rocky Marciano. He was one of the greatest fighters of all time. His 49-0 record speaks for itself. If I hurt Marciano’s family, I regret it.”

What Holmes did not back away from, not then and not now, is his belief that he deserved to win both of his fights with Michael Spinks, with the first loss a thinly veiled and successful attempt to keep him from sidling up alongside the sainted Marciano.

“There was no doubt about it,” he said of a decision he still regards as a cold slap in the face. “I knew what they were going to do to me. I knew if I didn’t knock him out, I wasn’t going to get the decision.” Nor is he alone in that contention, just as there are Spinks partisans who are just as insistent that the judges got it right.

Asked if he thought then, or does now, that he did not receive all the credit he was due from Holmes and his other persistent proponents of the conspiracy theory that refuses to die, Spinks said it shouldn’t matter at this point. The record book indicates he won, so that should be that.

“It was a close fight, but I did think I won,” he reiterated. “There’s no animosity between me and Larry. We get along. He’s not really sore about it anymore. At one of his golf tournaments that I attended, he took the microphone and said something about how he’d lost to me, but that wasn’t all bad because he made so much money for losing.”

What Holmes wants to make clear more than anything is that he wants to forever bury any hint that race is or should still be a part of the discussion. He said there was too much of that in the past, and still too much now. He pointed out that Gerry Cooney, the white guy against whom his high-visibility fight was neatly divided into opposing racial camps, as well as Spinks have been regular participants in his charity golf tournament.

“Half of my family is white,” Holmes pointed out. “I’m not a racist. I don’t have anything against white folks or anybody else. My son is getting ready to be married in a couple of weeks to a white girl. My daughter is married to a white guy.

“I didn’t really care about racial s— then, and to this day I don’t care about it. Gerry Cooney is my friend. Now, I didn’t like the decisions in my fights with Michael Spinks, but you can’t dwell on that. You got to move past that.”

Which might be one man’s way of saying that any lingering ghosts on that figurative grassy knoll overlooking a boxing ring where a fight took place 34 years ago should finally be allowed to just fade away.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Book Review3 weeks ago

Book Review3 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day