Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Flyweights of All Time: Part Four 20-11

The Top Twenty are in the can now. How do they compare to the other divisional Top Twenties?

Well the same clutch at featherweight was a ridiculous capture, starring immortals such as Henry Armstrong and Terry McGovern; Jack McAuliffe and Joe Brown likely outstrip their tiny cousins at the absurdly stacked lightweight; don’t even get me started on middleweight, where the likes of Mickey Walker, Freddie Steele and Jake LaMotta are appraised. But when it comes to their nearest relatives, the bantamweights, and their most distant, the heavyweights, flyweight compares directly. I think though, if I’m honest, the flyweights are probably bringing up the rear in terms of quality in the 20-11 bracket.

That said, the differences are slim – just like the differences that separate the fighters in this, the penultimate installment of a series that has taken more than half of one decade to produce.

#20 – Fidel LaBarba (1924-1933)

For a certain kind of fan, Fidel LaBarba will always be flyweight’s blue-eyed boy.

An amateur teen, an intelligent, well-spoken and humble New Yorker, LaBarba rose from obscurity to the world championship while still in his early twenties. It was a glorious story and it resounds through the decades.

That said, a pithy accountancy of LaBarba’s career at flyweight would be exactly two lines long.

LaBarba resigned the flyweight championship just months after lifting it to enroll in college; furthermore, many of the contests he partook between winning the title and resigning it took place at the bantamweight limit and even above. He was, in fairness, a growing boy but difficulties of his personal biology play no part in appraising his status at 112lbs.

He squeezed plenty into that brief time, however. In August of 1925 he defeated Frankie Genaro clean, a victory that remains arguably the best victory in all of boxing history by a teenager. It also made him the owner of the coveted American flyweight championship and the sudden passing of champion Pancho Villa shortly before meant he was also a top contender to the now vacant championship.

He annexed that belt in the first significant contest of 1927, taking the title against the doughty Scotsman Elky Clark. Clark was as tough as they come, stopped just once in his first professional contest back in 1921, and against LaBarba he needed every ounce of his stoicism as he was hammered from pillar to post by a fighter possessed. It was a violent beating that ended his career.

Traditionalists would rank LaBarba among the top twelve; personally, I don’t consider his resume is good enough even for this spot -but it was the manner of his dispatch of Genaro and Clark that most impress. Like Roman Gonzalez he outclassed some of the best available opposition, but in Genaro and Clark he had opponents worthy of his best.

Villa’s tragic death likely denied us one of the great flyweight showdowns.

#19 – Newsboy Brown (1921-1933)

What’s better than defeating a legendary flyweight like Frankie Genaro once? Well, beating him twice is a good start, something Newsboy Brown, real name David Mondrus, was able to do, locking him in front of LaBarba on any sensible list by my eye.

Brown and LaBarba shared an era, then, and did in fact try to settle their differences the old-fashioned way, two draws the result.

So, it is settled between them based upon common opposition. Brown first met Genaro in October of 1925, not yet in his absolute prime but certainly his vaunted body attack had matured; Brown deployed it and edged the narrowest of ten round decisions. The two met again in 1927 and the result was a familiar one – Newsboy Brown scrapped his way to a second ten round decision victory.

Brown then began to show the same patchwork of results the other great fighters of this golden age of flyweight boxing suffered. Nobody could remain consistent in such company and Brown dropped decisions to Willie Davies, Frenchy Belanger and Izzy Schwartz in the next twelve months. His loss to Schwartz was the most damaging. Brown had previously dominated Schwartz so his fifteen-round loss with a strap on the line was a surprise and one that hurt both his hunt for the legitimate title and his all-time standing.

Nevertheless, victories over Johnny McCoy and Speedy Dado marry well with his previous decision win over Schwartz and, most of all, those two priceless wins against the great Genaro.

#18 – Yuri Arbachakov (1990-1997)

Yuri Arbackavov was a genius, as perfectly balanced a flyweight as has ever lived. He boxed out of Japan, turning professional in 1990 and battering a series of professional losers and journeymen before landing an unearned title shot against world champion Muangchai Kittikasem whose twenty-one fights made him a veteran by comparison. He had been a professional a little more than two years.

Yuri destroyed Maungchai. He weaved a hideous attack around the stiffest of stiff jabs to the gut, wielding hooks and crosses around it like a deadly and hurtful web. It would be wrong to say Yuri owned a vicious body attack; more, he found openings, landed punches at all sites, his strategy based purely upon availability rather than a strategic or even tactical plan. It was breathtaking.

Certainly, Maungchai must have thought so upon being deposited both unconscious and face down upon the canvas by a picture-perfect counter right hand. But he was a good fighter, and a legitimate champion so he dusted himself off and took another shot at Yuri; he lasted one round longer, crumbling in the ninth.

It wasn’t just that right hand counter that was picture perfect; everything Yuri did came straight out of George Benton’s manual. Limber, fluid, with gorgeous footwork and exquisite punching form, all of these things and more could be laid claim to by the Russian. Here’s the problem: this was his summit.

He successfully defended against the superb Ysaias Zamudio in 1993 and butchered Hugo Soto, a fair challenger, in 1994. But every one of his other successful title defenses was against questionable opposition, men who, like he, had not earned their title shots. His apprenticeship was non-existent, his title reign was lukewarm and when he bowed out against Chatchai Sasakul in 1997 he left an incomplete legacy in his wake.

Yuri looked the part and probably had enough skill and innate ability that a top ten berth was within his grasp. As it is, he managed to miss out on almost every significant flyweight of his era bar Muangchai and Zamudio, including Mark Johnson – who might just have tested that riffing strategy and exposed the merest hint that he, too, may have been vulnerable to a concentrated body attack.

We will never know – and because we will never know, this is as high as Yuri can stand, despite the protest of boxing purists who all but faint at his perfectly executed movements. A long reign and those nine title defenses scrape him into the top twenty.

#17 – Rinty Monaghan (1932-1949)

Rinty Monaghan was often described as “scrappy”, which seems to denote a determination to win on the part of a fighter who lacked knockout power, but Monaghan was far, far more. He was far more in cementing his claim to the title against Jackie Paterson in 1948, certainly.

In the light of Paterson’s inactivity in defending his title there were those that tried to recognize Monaghan’s claim from 1947 when he soundly defeated the visiting Dado Marino over fifteen rounds and was elevated to champion by the NYSAC and the Irish board of control – but Paterson remained the champion in the eyes of traditionalists (including your writer) having never lost the title in the ring. Monaghan tied up the loose ends by matching Paterson in Belfast five months later. The two were no strangers to one another, Paterson having shocked Monaghan by knockout a decade before, then succumbing to vicious cuts in a rematch in 1946; in their 1948 rubber, the Northern Irishman left no room for doubt, as Paterson, now emaciated by his battle with the 112lb limit, was a mark for Monaghan’s swarming attack and huge variety of right hands.

Monaghan looked disorganized, but he was a beautifully balanced fighter. Nullify his booming, swiping, layered right-hand and he had a sneaky left hook and left jab to fall back on. Fighters of a given type might neutralize one, but they would rarely then be able to neutralize the other. His attack was too variable to see him out-boxed, he had to be outfought.

After Paterson failed to do so, blasted into submission and then unconsciousness in seven brutal rounds, Monaghan staged two defenses. In the first, against the number three contender Maurice Sandeyron out of Paris, he took a fifteen-round decision. In the second, against Londoner Terry Allen, he got “the fright of his life”, was perhaps lucky to escape with the draw and promptly retired.

But Monaghan was so much more than just that short title run. He had been operating among the elite since 1938 when he first bested Joe Curran; he stopped the class operator Ed Doran in four in 1945, then began his series with Paterson before first meeting Terry Allen, blasting him out in just a single round. Emile Famechon and Dado Marino both rated among the best of the time when he took them.

Monaghan suffered some losses, but he was much more likely to win, something he did well, often and against some of the best around.

#16 – Peter Kane (1934-1951)

Peter Kane is the division’s number two puncher.

He turned professional in Liverpool in 1934 and embarked on an unprecedented tear up through the British domestic scene, then the hub of flyweight excellence. On forty-one occasions a man came up to mark and was turned away by a fuselage of hard punches from a slugger who specialized in cracking un-broken chins. He stopped the brick-chinned Italian Enrico Urbinati in eight rounds in 1936; the granite-jawed Belgian Gaston Van de Bos later that same year; Pierre Louis, the Frenchman, early in 1937; and most impressively Northern Irishman Jimmy Warnock in four rounds that summer in front of 40,000. None of these men had ever been stopped before Kane got his blood-sodden paws on them and Warnock had just emerged victorious from a fifteen-round non-title combat with the genius Benny Lynch.

Kane’s defeat of Warnock earned him a shot at Lynch’s flyweight-title, but this proved a roundhouse swing too far for the brawler. Lynch countered Kane to death, stopping him in thirteen; but Kane, for anyone who isn’t paying attention, isn’t the type of man to go away and he earned himself a draw up at bantamweight the following year. Lynch, unable to make the 112lb limit, forfeited the title and Kane inevitably picked up the vacated championship against Jackie Jurich in 1938. Jurich hauled himself off the canvas five times to make the final bell.

Kane dropped the title in 1943 against Jackie Paterson by which time he had out-pointed ranked man Tiny Bostock over ten, twice bested top five contender Ernst Weiss, twice bested Valentin Angelmann, ranked four, which, when added to Louis, Warnock and Jurich, all highly regarded, and Joe Curran, also in the top five, resulted in one of a strong era’s tidiest resumes.

His title run, truncated by the war years, is unimpressive but the men he bested and manner he bested them in, was not.

#15 – Betulio Gonzalez (1968-1988)

Betulio Gonzalez remains one of Venezuela’s greatest fighters and, even for a flyweight, languishes rather underrated. A frustrating fighter to watch, he was capable of absolute brilliance, technically perfect smuggled uppercuts thrown on the inside, feinted lead and a cross-counter on the outside all well within his marshal grasp. He made technically difficult combinations look technically easy. Despite this, and despite the twenty years he spent in the ring, he could appear strategically moribund against the very best, bereft of a plan to hang his hat on.

When the problem was easy to solve though, he could be almost irresistible, as was the case in his 1978 crack at an alphabet strap held by the superb Guty Espadas. Espadas was on a seven-fight knockout streak and had done significant damage to significant names in lifting his belt, so Gonzalez set out to do the simplest and yet most difficult things: outfight the puncher toe-to-toe. The first four rounds are as sizzling and broiling as anything that can be seen at the poundage and is a must-see for fight fans; when the dust settled Gonzalez sought out and found his defensive rhythm, battling home for a narrow decision victory despite a series of quite astonishing rallies from his opponent.

So Gonzalez held a belt, but would never be the true linear champion. The reason was a valid one, however: Miguel Canto.

Gonzalez met this little giant three times between 1973 and 1976, twice with the lineal title on the line. The second of these contests was a brilliant exhibition of boxing and possibly Canto’s best performance, a left-handed clinic in excess of almost anything that can be seen on film. Gonzalez was turned away in a split decision, the same result as in their third and final contest. But in their first meeting in 1973, probably before Canto had entered his absolute apex, Gonzalez turned that result on its head winning on two cards on his home soil to mount a jewel in the crown of his storied resume.

Osamu Haba, Peter Mathebula and two victories over Shoji Oguma ensured that Gonzalez stood out even in this golden age of flyweights and sees him stand among the finest contenders to the lineal crown in history.

#14 – Sot Chitalada (1983-1992)

The mighty Sot Chitalada’s boxing career was truncated to just thirty-one fights, but his combat career was longer. He turned professional in 1983 as a storied Muay-Thai competitor and this helps to explain his winning the world flyweight championship in just his seventh contest. It was an astonishing feat but one that must be understood in a wider context.

Having smuggled the title away from Gabriel Bernal, Chitalada traveled to the UK for his first defense and stopped Charlie Magri on a cut in the fourth. He then returned home and re-matched Bernal in one of the most exciting flyweight title fights captured on film. Bernal caught Chitalada early with two peachy, herding hooks and dropped him neatly onto his right haunch. This knockdown defined the fight. Bernal, determined that his swirling southpaw pressure would pay, never stopped coming and even Chitalada’s vicious body-attack didn’t discourage him. The result, a majority draw, felt true in tone, Bernal’s knockdowns in the first and eighth key.

For his next trick, Chitalada turned over former champion Freddy Castillo before facing Bernal for a third time. Finally, Chitalada’s variety and accuracy separated himself from his old foe.

All this excitement means that Chitalada had dusted off three lineal flyweight champions (one of them twice) in just thirteen fights. Find me another fighter who successfully undertook a schedule like this in any weight division at any time in history and I’ll be impressed: wait, though. You’d have to go again – after losing his title to Yong Kang Kim in a raucous, weird, close fight out in Korea, Chitalada reclaimed his title in a nip-and-tuck rematch to beat yet another world champion.

During this process, I’ve been tough on fighters who take the alphabet route, fighting the selection of a corrupt ABC instead of one of the world’s better fighters and then complaining that his legacy is being disrespected. But the fighter disrespected it. Sot Chitalada is the Ying to that Yang. He consistently matched elite fighters and an elite resume was the result.

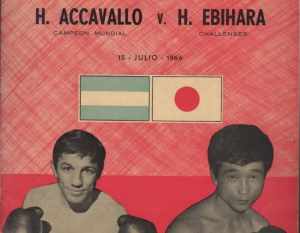

#13 – Horacio Accavallo (1956-1967)

Argentine technician Horacio Accavallo is perhaps the most underrated flyweight of all time, which is the same as saying the most underrated fighter of all time. He was of a type that was and remains unheralded, a steady, correct technician who could pop well enough to earn an opponent’s respect but not the excitement of the wider boxing world. A hero in his home country, his brilliance never translated into dollars. Crucially, he never boxed in America.

But he did amass an astonishing 75-2-6 ledger and on it are some names worth noting. His first loss came during a protracted stay in Italy when he matched an Italian to be every bit the legend in his home country as Accavallo was in his, Salvatore Burruni. Both men were novices, but it was Accavallo, far from home, who stole the decision over 8; Burruni avenged himself a year later, also in Italy and the rubber match between the two legends occurred some six years later. Both, by then, superstars in their native countries, Burruni traveled to Argentina to meet Accavallo, by then a belt-holder for the third and final time. All grown up, the Argentine dropped Burruni in the opening round and assaulted him viciously in the closing rounds. This was one of Accavallo’s great and underestimated strengths: his late rallies were channelled from some other realm of the heart and he rarely allowed any opponent to finish stronger than he.

Certainly, Burruni wilted. Then reigning as the world champion, he had refused to put the true title on the line against Accavallo and would never offer him the chance to take it from him. Consequently, the Argentine never reigned as lineal but he did defeat the lineal champion. In fact, he defeated two of them. The great Hiroyuki Ebihara (see below) ruled the world in 1963 and 1964 and must be regarded as one of the greatest of all the flyweights. Accavallo met him twice, both times as his own career was running down and while Ebihara was arguably trickling past his own astonishing prime, he was also on a fourteen-fight winning streak that included two dominations of the excellent Efren Torres. Nobody other than Pone Kingpetch had beaten him since Fighting Harada had turned the trick in 1960.

Accavallo beat him clear in their first fight in 1966 but it is the second contest the following year that has drawn the eye of the historian since. This, Accavallo’s last, is rumored to have been a questionable decision and the reason he went into retirement. This second claim is false; Accavallo suffered an injury and after an 83-fight career, he never fully recovered. The first, too, is false and this can be seen online. The second meeting between these two is captured on film and shows a tight fight, controlled, barely, by Ebihara early, arguably dominated by the Accavallo late. One could make an argument for an Ebihara card, but it is certainly no problem to deliver one for Accavallo. A majority decision for the 5’2 southpaw Argentine saw him once again overcome the height advantage his opponents invariably held over him.

Toss in his victories over Katsuyoshi Takayama and Efren Torres, the nine uninterrupted years he spent ranked among the very best flyweights in the world, the 48-fight unbeaten streak he turned in during his prime, the fact that he managed 5-1 against men on this list and it is clear that Accavallo is clearly good for his spot.

His absence from the IBHOF makes a mockery of that institution.

#12 – Hiroyuki Ebihara (1959-1969)

Legendary Japanese southpaw Hiroyuki Ebihara ruled the world in 1963 and 1964, his reign amounting to just four short months. A footnote, then, in flyweight championship history. But Ebihara suffered some extraordinary company during his career, and those monstrous flyweights inflicted most of those losses.

He dropped a ten round decision to Fighting Harada in his tenth fight in early 1960 and lost twice to Horacio Accavallo, then dropped a decision in his last ever fight. His other loss was posted to the giant of flyweight boxing, Pone Kingpetch.

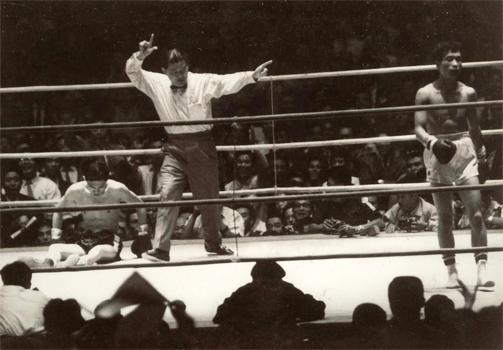

Kingpetch was in possession of the title when Ebihara got his shot in 1963. Kingpetch’s brilliance as a boxer was probably only matched by men ranked among the top division’s all-time top ten and he presented a singular problem to any challenger. Ebihara’s solution was equally pointed; in the very first round he landed the type of southpaw lead that turns durable fighters to jelly. Kingpetch, being made of steel, found his feet and staggered uncertainly on his slim legs. No flyweight in history would have survived the bombardment with which Kingpetch was greeted. A similarly terribly punch deposited him for a second time and the champion was rendered to the canvas, able only to raise his head uncertainly, all other portions of his body a victim of the messages of disaster his brain dispatched. Ebihara (pictured in black and white) stood the flyweight champion of the world.

The rematch with Kingpetch was a desperately, desperately close majority decision that would have gone to Ebihara in Japan as surely as it was reasonable for it to go to Kingpetch in Thailand.

And that was all for Ebihara and the championship, but he was more than the championship. He all but cleared up in the East, blasting out Shigeru Ito in two rounds just months after Ito extended Fighting Harada the distance, bested chief domestic rival Tsuyoshi Nakamura three out of four times (the fourth a draw) before travelling to America and crushing the ever-dangerous Efren Torres in seven. Jose Severino, then ranked #4 in the world, was his last great effort before Bernabe Villacampo retired him in late 1969.

#11 – Willie Davies (1924-1933)

“Wee” Willie Davies had a problem, and the problem was Midget Wolgast. Wolgast was a problem for a lot of hollow-eyed, newly-crushed flyweights in the 20s and 30s, but Davies had the questionable honor of meeting him on no fewer than seven occasions, and on no fewer than six of these found himself desperately seeking the answer to the often heard question asked by Wolgast’s opponents: “What happened?”

What happened was he was trapped in an era with perhaps the most unboxable flyweight of all and found himself unable to cope with his ludicrous feats of speed and punching. Betulio Gonzalez had Canto, Davies had Wolgast and neither would be champion. Sometimes, that’s just the way it goes.

Davies did manage to win a single contest against his perennial foe, their first, fought over eight rounds in 1927. Thereafter he had to settle for running Wolgast so close he was sometimes deemed worthy of a draw he never received. Fortunately, Davies had other exceptional competition against whom to prove his greatness, and this he did, plundering three wins and two draws from his six matches with “Black” Bill. What Wolgast was to Davies, Davies was to Bill. Their fights were raucous, heated and close, but as in the former case so the cream rose to the top.

He dominated a four-fight series with Izzy Schwartz, dominated a sliding Frankie Mason, out-fought and out-slicked coming contender Emil Paluso and, in possibly his best night’s work, won a decision by a sliver against the superb Newsboy Brown.

Shifty, quick and armed with an iron jaw and clever defense, Davies served out his inevitable downfall up at bantamweight. At flyweight, in his glorious prime, the gold eluded him only by virtue of the glimmering company he kept. It’s a cliché because it’s true: the man was a champion in any other era.

And only the ten greatest flyweights in history stand between him and a spot in the final installment.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers