Featured Articles

From Womb to Tomb, Sonny Liston’s Fate Was Seemingly Preordained

In Pariah: The Lives and Deaths of Sonny Liston, a remarkable 90-minute documentary on the rise and fall of former heavyweight champion Charles “Sonny” Liston, viewers are apt to discover that any preconceived notions they might have had about the baddest man in boxing history are, by turns, both legitimate and misinformed.

No matter what fight fans think they know of Liston, it’s a fairly safe bet more opinions will be shaped by watching the Nov. 15 premiere of Pariah (9 p.m EST and PST) on Showtime. While questions about how and why Liston died remain a source of speculation, the disparate elements of his conflicted, turbulent life suggest that much of the actual truth about him, good and bad, is forever destined to be a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Inspired by The Murder of Sonny Liston: Las Vegas, Heroin and Heavyweights, a book authored by Shaun Assael, the documentary examines the pros and cons of the oft-arrested, twice-incarcerated, mobbed-up wrecking machine who did not so much defeat opponents as to eviscerate them. Viewers – especially white people old enough to be familiar with the era in which he rose to prominence — are left to decide for themselves if Liston really was or deserved to be representative of their deepest fears, or a frequent victim of circumstance who wanted nothing more than some positive acceptance instead of the widespread loathing to which he had become accustomed.

But the journey from villain to hero is never smooth for someone with Liston’s checkered background, and especially so given the social unrest of the late 1950s and early ’60s. Hasan Jeffries, a black assistant professor of history at Ohio State University, said that Liston, a product of the Jim Crow South, was widely considered to be “America’s worst nightmare” and a “literally dangerous Negro,” someone who was “unafraid of white people as demonstrated by his consistent encounters with police.”

When he returned to his adopted hometown of Philadelphia after his title-winning, one-round blowout of popular but hopelessly outclassed champion Floyd Patterson, and discovered that there was no one at the airport to celebrate his triumph or to finally recognize him as something more than a glowering bully with a lengthy rap sheet, an increasingly bitter Liston decided that he might as well settle for being who and what the masses thought he was instead of trying to change millions of minds that had long since been made up.

Liston’s sudden embrace of his malevolent reputation reminded me of a line of dialogue from The Vikings, a 1958 movie in which a fierce Norse warrior, played by Kirk Douglas, is unable to win the affection of a captured British beauty played by Janet Leigh. “If I can’t have your love,” Douglas, as Einar, defiantly tells Leigh’s Morgana, “I’ll take your hate.”

Not that Liston, the 24th of 25 children born to an Arkansas sharecropper who was less a father than a tyrannical family overseer, ever chose to be hated. But neither was he apt to be idolized in the manner of, say, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano or the man who would ultimately succeed him upon the heavyweight throne, Muhammad Ali. Liston, who could neither read nor write, lacked the basic communication skills that might have gained him a bit more favorable press, and his personification of danger was accentuated by a withering glare that left more than a few opponents frozen with fear before the opening bell rang.

“He was a real badass, a real menacing force,” Mike Tyson, a future heavyweight champion with a similar gift for intimidation, said of Liston. “Sonny could pull it off. I could pull it off. Not a lot of people could pull it off.”

It would be a disservice to Liston, however, to say that the main weapon in his arsenal was a gift for winning staredowns. Scary as Liston was simply by standing there, he was so much more so when he began whaling away at flesh and bone as might a burly lumberjack chopping down a thin tree. Forget so-called experts’ arbitrary rankings of the hardest punchers ever to lace up a pair of padded gloves; Liston’s knockouts were spectacular for their savagery, toppled foes crashing to the canvas as if they would never again get up. He needed only 69 seconds of the first round to put a decent journeyman, Wayne Bethea, down and motionless, in the process dislodging 16 of Bethea’s teeth. Nobody in the fight game supplied oral surgeons with more patients in need of emergency treatment than Sonny Liston.

By reputation, Liston, who compiled a 50-4 record with 39 KOs from 1953 to 1970, was a huge heavyweight for his era, but he stood just 6-foot-1 and weighed in around 215 pounds during his prime. Then again, Liston’s unextraordinary height and heft were not his measurements of consequence. His 86-inch reach, those incredibly long arms extending down to massive fists the size of a catcher’s mitt, were. Liston might have had the most devastating jab ever, as accurate as Larry Holmes’, only harder. Sonny could use that jab as a range-finder when necessary, but its concussive force was such that the numbers-crunchers at CompuBox today would be obliged to categorize it as a power punch. He could knock a man down and even out with that jolting jab, and sometimes did.

“Sonny’s left jab was a nose-cracking, teeth-busting experience,” offered Randy Roberts, a boxing buff and assistant professor at Purdue University who serves as one of the documentary’s talking heads. “They said getting hit with his jab was like getting hit with a pole.”

Liston’s penchant for destruction inside the ropes, had he not come along when he did, might have made him as rich and celebrated as Tyson would become 50 years later. So why wasn’t he? Liston had so many brushes with police that fibers from their blue serge uniforms clung to him like permanent lint. Not only was he arrested 19 times and did two prison stretches, but cops in St. Louis and Philly, cities that for a time served as his home bases, tracked his movements as a meteorologist would an impending storm. Perhaps all that extra attention was justified at times, but Liston’s freedom of movement was so inhibited that he often felt as if he were somehow encased in an invisible jail.

“There was nothing they didn’t pick me up for,” Liston once complained. “If I was to go into a store for a stick of gum, they’d say it was a stick-up.”

It was to Liston’s benefit and detriment to have turned his career over to organized crime figures Frankie Carbo and Blinky Palermo, boxing manipulators who had enough clout to not only advance his career but to get him sprung earlier from prison sentences that would surely have been longer were he not a possible future heavyweight champion. The downside of the arrangement is that the Feds spent a lot of time looking into the nefarious activities of Carbo and Palermo, which meant they also had a thick dossier on Liston. It did not escape the FBI’s attention that the non-boxing “jobs” for Liston lined up by his influential backers to gain him early release were something less than fully above board.

“He’s a leg-breaker for the mob, he’s an alley-dweller,” Roberts noted. “Sonny never walked on well-lit streets. Sonny lived in darkness.”

Maybe so, but there are more than a few boxing historians who have tried to determine what made Liston tick. A case can be made that inside those shadows in which he was obliged to exist there was a better, brighter version of himself almost desperate to break out.

“I don’t think the general public ever knew the real Sonny Liston,” opined Nigel Collins, former editor of The Ring magazine. “They knew the persona, the thug-like guy who just knocked everybody out, was associated with the mob and had been in jail. He wasn’t really that. That was a front. That was what he needed to protect himself, and also to intimidate his opponent. He was a very sensitive person. He could be hurt easily.”

That description of Liston was seconded by his wife, Geraldine, who described her husband as “a good man and a kind man, and worthy of a chance to contribute to society.”

To Sonny’s way of thinking, his ticket to validation as a human being was to gain the heavyweight championship then held by Floyd Patterson, a nice guy but lesser fighter whom Roberts called the “Sidney Poitier of boxing.” It wasn’t necessarily a compliment. Patterson’s shrewd manager-trainer, Cus D’Amato, had managed to supply Patterson with a steady stream of marginally qualified and eminently beatable challengers, but D’Amato wanted no part of Liston. The first of the two title bouts between Patterson and Liston came about only because Floyd, embarrassed by the spreading public perception that he was more protected than the gold in Fort Knox, demanded that Liston be given the chance at the title he had earned with those ham hock fists.

Jerry Izenberg, the esteemed sports columnist for the Newark Star-Ledger, visited Patterson’s well-manicured rural training camp before checking in on Liston’s, which was urban, grittier and unquestionably better suited to a reformed leg-breaker on a mission.

“He’s got two chances – slim and none,” Izenberg said in recalling his impressions of Patterson’s preparations for a fight few gave him a chance to win, or even to finish in an upright position. After Izenberg got a glimpse of Liston’s laser-beam focus, he amended his original assessment. “I’m saying those two chances for Floyd, slim and none? Slim just went out the door.”

The fight, such as it was, took place on Sept. 25, 1962, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Custer had a better chance at the Little Bighorn than Patterson did against Sonny. The annihilation required only 2 minutes, 6 seconds to complete, whereupon the humiliated Patterson snuck out of the arena in disguise, and Liston returned to Philadelphia, foolishly expecting the hero’s welcome he believed to be his reward for all those hard years of poverty and dues-paying.

“There are people who don’t want me to be there (as champion),” Liston upon attaining the title. “Regardless of them, I intend to stay there and I promise everyone that I will be a decent, respectable champion.”

Jack McKinney, then the Philadelphia Daily News boxing writer and the only media person in town who had earned Liston’s trust, called City Hall to see if a group of dignitaries could be on hand to greet the new champ. But there was no brass band at the airport, no cheering fans, no smiling politicians to pat the not-favorite son on the back and say that all had been forgiven. Nor was the reaction to his seemingly improved lot in life any warmer elsewhere.

“I didn’t expect the President to invite me into the White House, but I sure didn’t expect to be treated like no sewer rat,” Liston grumbled.

The chip on his shoulder now the size of a log, Liston showed up for the July 22, 1963, rematch at the Las Vegas Convention Center more determined than ever to cruelly demonstrate his superiority over Patterson and any other heavyweight that might be foolish enough to share the ring with him. Like Kirk Douglas’ Einar, if he was unable to win the public’s love, he would revel in its hate. Again Patterson was destroyed in the first round, the fight a virtual replica of the original.

“The only difference,” Collins said of the do-over, “is that it lasted four seconds longer.”

No one could have known it at the time, but the second demolition of Patterson would be Liston’s only winning defense of the title he had so relentlessly sought and, many figured, would hold in a vise-grip for at least the next five years. But even before Liston left the ring, a conqueror beyond compare, an audacious young upstart entered his space and loudly berated the newly crowned champion. His name, at least at for the time being, was Cassius Clay.

“I want you! I want you! You ugly!” Clay yelled at a seemingly bemused Liston, who regarded the impudent kid as he might a Martian who had just stepped off a spaceship. But Clay kept up his campaign to force a showdown with Liston where it counted. In the weeks that followed, he repeatedly demeaned Liston in newspapers and on TV. And if those affronts weren’t enough to produce the desired effect, Clay went so far as to physically confront the man he had dubbed the “big, ugly bear” in Vegas, a mob town to which Sonny had relocated and enjoyed a level of tolerance he had been unable to find in St. Louis or Philly. Clearly Liston would have no peace of mind until he did unto this loudmouth what he had twice done unto Patterson. He was a 7-to-1 favorite to do just that when the fight took place on Feb. 25, 1964. Some media members were concerned that Liston was determined to, and quite capable of, literally beating Clay to death.

But on a night where one legend died and another was birthed, Clay fought through a tense fourth round in which an astringent that had gotten into his eyes and made it difficult for him to see. Flashing the speed of hand and foot for which he would become renowned, Clay, his vision cleared, increasingly took control of the contest until Liston, gashed below the right eye and with a large mouse under his left eye, declined to come out for the seventh round. He cited a shoulder injury as the reason he was unable to continue.

In boxing, it is one thing to lose. It is quite another for a fighter, especially a champion of Liston’s magnitude, to surrender. Author Robert Lipsyte was among those who took him to task, saying, “If you’re heavyweight champion, you die trying. But he just kind of sat there. He gave up. Why did he give up? This, of course, is the mystery at the heart of it all. Did he give up because he was in such terrible agony he couldn’t move? Did he give up because he suddenly realized he couldn’t win this fight? Did he give up because he’d been paid to dump it? Who knows?”

But the plot, as the saying goes, soon thickened. Cassius Clay announced the following day that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, more commonly known as the Black Muslims, and now wanted to be known as Cassius X, a stopover on the way to a more permanent identification as Muhammad Ali. It was as if he had become the bad guy, at least to a segment of the American populace, with the disgraced Liston now viewed as the possible savior and re-capturer of a championship that had fallen into presumably radical hands. The rematch was to take place on June 25, 1965, in Lewiston, Maine, a sleepy outpost (the town was mostly known for its factory that manufactured bedspreads) near the Canadian border which stepped up when Boston, the originally announced site, bailed.

“Liston got more cheers than Ali,” recalled journalist Don Majeski of the fighters’ respective ring walks. “They finally said, `Well, between these two, the lesser of the two evils is Sonny Liston,’ so we’ll cheer this ex-convict who lost his title on his stool rather than to root for a guy who says he’s a Black Muslim separatist. (Liston) enjoyed that. He sort of basked in that kind of glory for the first time in his life.”

Or he did, for a fleeting moment.

“But then what happened was the Kennedy assassination of boxing,” Majeski continued. “Everyone has an idea, but nobody knows the truth.”

What happened was that Ali landed (or missed) with a flicking right hand in the first round that sent Liston careening to the canvas, where he floundered around like a reeled-in fish tossed onto the bottom of a bass boat. To this day there are those who are convinced that Liston, for reasons unknown, took a dive, an argument countered by Ali loyalists who insist that the punch was legitimate and powerful enough to fell even a big, ugly bear.

Assael straddles no fences on the issue. His position is that Liston purposefully went into the tank.

“Why fix the fight?” Assael asks, rhetorically. “That’s where the secret percentage theory comes in, which is that Sonny had agreed to an under-the-table deal to get a cut of Ali’s future earnings if he went down. It’s exactly what a mobster would have done, and it’s exactly what I think Sonny did do.”

In any case, Liston – whom former fight fixer Charles Farrell insists was “the greatest heavyweight who ever lived … a bonafide monster” – had taken a downward turn from which there could be no recovery. He would fight 16 more times over the next five years, winning 15, but he was, as the documentary’s title attests, a pariah.

“After the second fight (with Ali), Sonny’s a dead man,” Assael said. “He’s not only just reviled, he can’t even get a job. Boxing commissions won’t license him … Sonny was toxic. I mean, really radioactive.”

The mystery of Sonny Liston took an even more tragic turn when his decomposing body was discovered at his Las Vegas home on Jan. 5, 1971. An autopsy indicated his death might have owed to an overdose of heroin, which those who knew him well insist could not have been the case because Liston was almost paranoid in his fear of being stuck by a needle.

“The medical examiner called it natural causes, but nobody around Sonny believed that,” Assael said. “Everybody believed he was murdered. So many people wanted Sonny dead. The only question was, who got to him first?”

Larry Gandy, a Vegas cop, was among those who saw the body. “It didn’t even look like Liston, he’d been dead for so long,” Gandy said. “He’d been dead four or five days. He was bloated, full of methane gas. It really made me sick to my stomach because he’d been such a predominant figure in the sports world. It was a terrible, disrespectful way for him to go.”

Gandy’s expression of compassion might or might not be genuine since the documentary hints at the possibility of his having some measure of culpability in Liston’s demise, in mob retaliation for Liston’s final fight, on June 29, 1970, in which he defeated Chuck “The Bayonne Bleeder” Wepner on a ninth-round stoppage brought about by numerous and severe cuts to Wepner’s well-sutured face.

“Liston was not brought into that fight to win,” said Farrell. “I believe the Wepner fight was a deal that went terribly, terribly wrong.

“As the rounds went by, Liston couldn’t find a place to fall, Wepner’s increasingly beat up and eventually the fight gets stopped because of the cuts. Liston won the fight. It’s a series of miscommunications where nobody does exactly what they’re supposed to do. The mob lost a lot of money and there were dire circumstances.”

In the end, all that is left of Sonny Liston is a headstone in a Las Vegas cemetery and a raft of recriminations and might-have-beens. For every boxing historian who includes him among the greatest and most fearsome heavyweight champions of all time, there is another who sees only the warts and blemishes of perceived transgressions committed both inside and outside the ring. The International Boxing Hall of Fame seemingly leans more toward the former, as evidenced by Liston’s 1991 induction.

“You can always make a case for someone’s exclusion,” Bert Randolph Sugar, then the publisher of Boxing Illustrated, told me for a story I did on Liston’s posthumous enshrinement by the IBHOF. “It depends on how moralistic you want to be. But remember, this is boxing we’re talking about.”

Upon reflection, it is somewhat curious that Ali, who generated so much fear and mistrust for the rematch with Liston in Lewiston, and for some time thereafter, evolved into such a sympathetic and beloved figure, widely acknowledged as the GOAT (Greatest of All Time). Also, upon reflection you have to wonder how the career paths of he and Liston would have proceeded had a semi-blinded Ali’s demand that trainer Angelo Dundee cut off his gloves before the fifth round of his first fight with Liston been granted.

What is indisputable is that boxing, so rich in stories about great and flawed fighting men, needs more documentaries of this quality that peer behind the curtain of what fans only see on fight night, giving insight into the whole person. Then again, how many prospective subjects are capable of taking viewers on the kind of roller-coaster ride that Sonny Liston’s tumultuous journey did?

“There was one thing that Sonny was better at than boxing, and that was compartmentalizing himself,” Assael said. “He could be a loving husband, he could be a womanizer, he could be a criminal, he could be a boxer. That’s what he was a master at – boxing and being able to lead so many different lives. There were so many men inside that one man.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

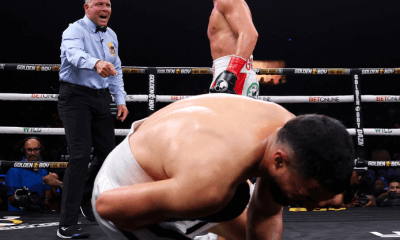

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

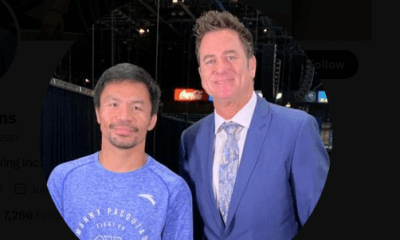

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons