Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 79: Boxing 101 (Part One)

Avila Perspective, Chap. 79: Boxing 101 (Part One)

In a dusty room in a loft-style apartment in Montebello began my adventure into the world of prizefighting as a journalist.

A very small throw-away newspaper that was circulated in the San Gabriel Valley area of Southern California was looking for a writer. The publisher had been printing left wing newspapers for more than a decade when he realized there was no financial reward.

One day this publisher ran into me at a supermarket and asked if I would be interested in writing for his brand-new publication. The content, he added, would be left to my whim.

For about a week I thought about what content would suit his readers. The newspaper was going to be circulated at night clubs, bars, restaurants and fast food joints in Pasadena, East L.A. Rosemead, San Gabriel and Montebello.

Catching the eye of the reader was key and I also needed a topic that wouldn’t date so quickly. After eliminating a few sports, I realized that boxing suited this new newspaper perfectly. Most of the people reading would be Latino and most Latinos love boxing. It’s also a sport that is based on big moments and big events.

It was April 1985 and one of the lesser known stars of the boxing world was a light flyweight world champion named Jung Koo Chang. His other moniker was the “Korean Hawk” and he would terrorize the world of 108-pounders from 1983 to 1989. I wrote my first feature on this little-known terror.

But in that same month a tantalizing fight was taking place in Las Vegas between Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns on April 15. It would be the first actual prize fight that I would sit down and write an analysis on. That epic fight was my baptism into the world of boxing journalism. It remains one of the greatest three-round fights in history.

For two years I scavenged sports pages of newspapers, magazines and other throw-away newspapers looking for boxing material. Our newspaper was doing pretty good and the publisher was pleased by the results. According to him the owners of the clubs and restaurants saw people going into their places of business looking for our newspaper. They wanted to read about boxing.

In 1984 the legendary Main Street Gym closed its doors and in 1987 the world of boxing lost Aileen Eaton who passed away in November. She had promoted boxing for decades and following her death the Olympic Auditorium no longer produced weekly shows.

With the departure of the Main Street Gym and Eaton, the local Los Angeles newspapers virtually eliminated the sport of boxing from their beats. In 1989 the Herald-Examiner shut its doors and with no stiff competition the Times had no real rivals to keep them headed in the right direction.

For five years I wrote for the L.A. Times and during that span it was always a battle convincing sports editors that boxing was not dead just because the Main Street Gym and Eaton were no longer around. Sports editors always think they know best. Usually, they have no actual sports background aside from journalism. Most definitely they have no expertise other than dabbling in sports here and there. And when it comes to boxing, they have zero knowledge other than watching it on television once in a while. It’s not completely their fault.

From birth I was raised in boxing. I’ll get to that later.

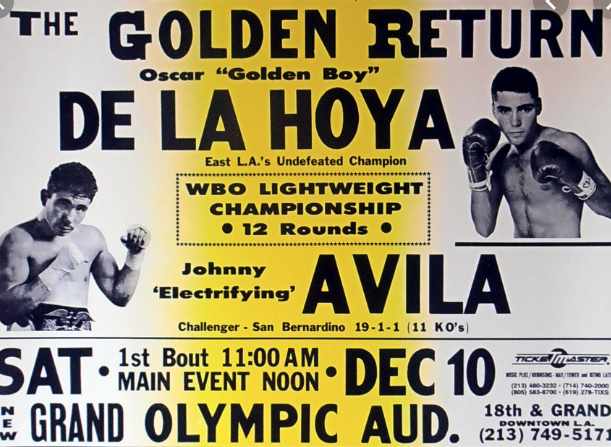

The Second Golden Boy

Around 1993, Oscar De La Hoya arrived on the pro boxing scene and with him began a reboot for boxing on the West Coast as his success and popularity increased.

When girls of all ages begin flocking to boxing cards it sparks interest from all sectors. Even the sports editors take notice from behind their dusty desks and myopic mind sets.

De La Hoya’s media success was slow at first as newspapers and television networks drudgingly got up off their butts to cover his fights. Though he was born and raised in East Los Angeles and was the only American to win an Olympic gold medal in boxing at the 1992 Barcelona Games, the media was slow to cover his ascent.

I was reporting news for the Times but not sports news. One of the editors knew about my East L.A. background and asked me to do a feature on De La Hoya’s influence at his old stomping grounds. That was my actual re-introduction to covering the boxing world in 1993.

Because of this feature on De La Hoya, I connected with the original Golden Boy, another East L.A. fighter named Art Aragon. During his span of success from the 1940s to 1960s, the original Golden Boy could pack an arena like the Olympic Auditorium and Hollywood Legion Stadium. He was gold.

At first Aragon poo-pooed the Golden Boy label given to De La Hoya. Seven years later he nodded that De La Hoya was indeed an even better Golden Boy than he had been after winning several division world titles and selling out the Staples Center that had just opened in October 1999.

Though De La Hoya was beaten by split decision against Shane Mosley, his popularity and financial drawing power made him a powerful force not only in boxing, but the sports world period.

Since 1993 the sport of boxing has flourished and grown to unimaginable levels never seen before in Southern California. More than 100 gyms fire up their lights and host dozens of fighters each day of the week except Sundays.

Boxing has become an invisible force in the Southern California landscape and has now spread to Texas, Arizona and Nevada like radiation spread from an Atomic blast. Prizefighting permeates like a blanket over the entire Southwest region of the US and not in niche sport fashion.

Back in the 1990s you could count on one hand the number of boxing gyms in Los Angeles. Las Vegas was another place where three or four gyms provided a place to train. Today both areas have more than four dozen gyms each within their city limits.

Branching Out

De La Hoya started his own promotion company Golden Boy Promotions in 2002 and continues to succeed. He has the top earner in prizefighting with Mexico’s Saul “Canelo” Alvarez who signed a $365 million dollar deal with DAZN.

From Golden Boy promotions spawned Premier Boxing Champions after Al Haymon split from the L.A.-based company and began his own boxing organization.

One of the key directions PBC took was reinvigorating the East Coast and African American prizefighting. They had taken a severe hit when it came to getting exposure in the fight game. Most of the action was taking place in Las Vegas and very little in New York City or the surrounding region.

In 2010, Haymon had several fighters including Chris Arreola. But soon he was signing multiple boxing prospects, especially after the 2012 London Olympics. Suddenly young fighters like Errol Spence Jr. Keith Thurman, Shawn Porter, Danny Garcia, Deontay Wilder and Daniel Jacobs were showing up on fight cards.

Some fighters failed but most proved to be very talented.

The best of the Haymon-advised fighters was, of course, Floyd “Money” Mayweather who was toppling the older generation of champions and now headed to a collision course with Canelo Alvarez in a battle of undefeated fighters.

Mayweather and Alvarez met in the boxing ring on September 14, 2013.

(Part 2 begins next week)

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision