Featured Articles

Corrie Sanders’ Upset of Wladimir Klitschko Always Overshadowed by Ali-Frazier

Corrie Sanders’ Upset of Wladimir Klitschko Always Overshadowed by Ali-Frazier

There are certain dates in boxing that are so consequential they are remembered annually, with reverence, for their historical significance. Perhaps no date fits that description more than March 8, 1971, the night when Joe Frazier scored a 15th-round knockdown of Muhammad Ali en route to winning a hard-fought, unanimous decision in Madison Square Garden in the “Fight of the Century.”

The upcoming anniversary of that remarkable event marks 49 years since “The Greatest” and “Smokin’ Joe” made magic together for the first of their three times sharing the ring, and the familiar written and spoken remembrances will again pay homage to arguably the most anticipated boxing match of all time. But the real tsunami of tributes will come in 2021, on the 50th anniversary of a megafight that seized the world’s attention as none before or since.

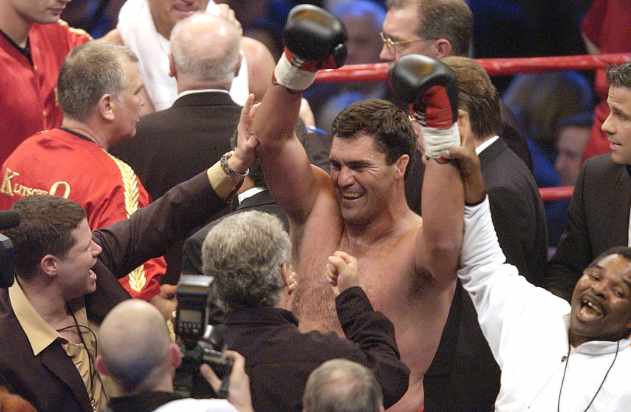

But there is another notable heavyweight fight that took place on another March 8, not exactly overlooked by history, but understandably relegated to a lesser place in a pecking order that forever shall reserve the top spot on that date for Ali-Frazier I. Still, Corrie Sanders’ shocking, second-round stoppage of WBO titlist Wladimir Klitschko on March 8, 2003, in Hanover, Germany, merits recognition both as a monumental upset and as a reminder that those who do not learn from history are sometimes obliged to repeat it.

Not exactly on the same elevated plateau as Ali-Frazier I, but not too far below it, is the celebrated date of Feb. 11, 1990, when Buster Douglas, a supposedly no-chance challenger to Mike Tyson’s supposedly invincible heavyweight championship reign, transformed the 42-to-1 odds against himself into the most stunning upset ever in boxing, and maybe in any sport, when he knocked out Tyson in 10 rounds in Tokyo. You say that Tyson went into that bout underprepared and overconfident? That Douglas dared to believe he was more than just another of Iron Mike’s designated victims? All true, but the parallels between Tyson-Douglas and Wlad-Sanders are eerily similar and cannot be dismissed.

Just as Douglas was generally considered to be a talented fighter whose mental lapses and indifferent approach to training made him less than he could have and maybe should have been, so, too, was Sanders, a 37-year-old South African southpaw, viewed as something of an underachiever, despite the 38-2 record with 30 KO victories he brought into his matchup with the younger and arguably more naturally talented of boxing’s Klitschko brothers.

Making the sixth defense of the WBO title he had won on a unanimous decision over slick-boxing southpaw Chris Byrd on Oct. 14, 2000, Klitschko was a huge favorite over Sanders, a Buster-like 40-1 long shot whose lack of peak conditioning for more than a few of his fights had become a recurring theme. When the always-impressively-muscled Wlad, whose intimidating nickname was “Dr. Steelhammer,” looked at Sanders, the fleshy guy bereft of six-pack abs, it must have been much the same as when Tyson made the mistake of writing off Douglas as just another fat impostor who would fall down the first time he got nailed solidly.

“He was what people in boxing call a `bum,’” Klitschko said in 2009 of his impression of Sanders, which soon proved to be incorrect. “I was tired. I’d been busy. I went into the ring thinking I’ll knock this guy out in one round and go home.

“This is the worst way to think. It’s a psychological disaster. You can’t think about vacation when you’re about to step in the ring. In my entire career, nobody ever beat me (like Sanders did).”

Klitschko’s miscalculation was apparent to HBO analyst George Foreman even before Sanders floored the Ukrainian twice in the first round and twice more in the second. Big George noted that Klitschko was “bone-dry” before the opening bell, a sign that he had not warmed up properly in his dressing room before making his way to the ring.

“Wladimir Klitschko seems so perfect, you wonder what’s wrong with him. Can Corrie Sanders find out?” Larry Merchant, another member of the HBO broadcast crew, said of the awe-inspiring man who had come in on a 16-bout winning streak, 15 of those victories coming inside the distance, including put-aways of such quality opponents as Axel Schulz, Monte Barrett, Frans Botha and Ray Mercer.

What was wrong with Wlad was something that had been demonstrated before, in his only pro defeat, an 11th-round TKO against American journeyman Ross Puritty on Dec. 5, 1998, and would again be demonstrated in losses inside the distance against Lamon Brewster and Anthony Joshua. Even in a unanimous, 12-round conquest of Samuel Peter on Sept. 24, 2005, in Atlantic City, N.J., Klitschko had to overcome three trips to the canvas. For all his obvious strengths, which are sure to gain him first-ballot induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2021, what “Dr. Steelhammer” lacked was a granite jaw. If you caught him just so, he could and would go down.

Whether or not Wlad’s falsely inflated sense of confidence for the Sanders fight extended to his trainer, Fritz Sdunek, or older brother Vitali Klitschko, the future WBC heavyweight titlist who also was a member of the corner team on that date, is a matter of conjecture. What is indisputable is that Vitali, clearly upset that referee Genaro Rodriguez had stopped the bout less than a half-minute into the second round, a reasonable action given those four knockdowns in quick succession, angrily confronted Sanders, shouting his intention to gain either revenge or a restoration of family pride, take your pick.

“This belt belongs to us!” Vitali, who had made a promise to his mother to always “protect” his younger brother, yelled at Sanders. “It is family property! You fight me next!”

For his part, Sanders, who figured he had just earned the right to savor his career highlight, felt Vitali’s vitriolic display was an improper intrusion.

“He should have let me have the moment, but he was shouting this and that,” the normally laid-back Sanders said of the tense exchange. “It was me who deserved the belt that night, no one else. He had no right to get into the ring as it was my time and not his. I simply told him, `I’ve beaten your brother and next time I’ll beat you.’”

As things turned out, it was indeed Vitali who got the next crack at Sanders, even though a do-over with Wlad seemingly was made to order for HBO, which, if rumors are correct, hadn’t been all that hot to televise the just-concluded fight, the consensus in the cable giant’s executive offices being that Wlad was so superior that Sanders would put up token resistance at best. But then Sanders vacated his newly won WBO title in December 2003 so that he could concentrate on a challenge for the presumably more prestigious WBC belt, which had become vacant in the wake of Lennox Lewis’ retirement. Lewis had retained his championship in his final fight, a sixth-round stoppage of a badly bleeding Vitali Klitschko on June 21, 2003, but he trailed on all three official scorecards at the time. HBO had no qualms whatsoever in signing off on a pairing of Vitali, known as “Dr. Ironfist,” with Sanders in a pugilistic version of the Hatfields vs. the McCoys.

Vitali avenged Wlad’s defeat by stopping Sanders in eight rounds on April 24, 2004, at Los Angeles’ Staples Center, but it was no cakewalk for the winner. Sanders, an all-around athlete who had played rugby and cricket as a schoolboy and had become so proficient at golf that he considered trying out for the PGA Tour, would go on to win three more bouts, but he called it quits, at 42, when he was TKO’ed in one round by 30-year-old Osborne Machimana on Feb. 2, 2008, for the South African heavyweight title.

The perspective of time has a way of either illuminating or diminishing the careers of certain fighters who are not easily categorized. In retrospect, Cornelius Johannes Sanders was, like Buster Douglas, probably better than what he was given credited for being throughout much of a career played out in relative anonymity. Sanders – who bore an unfortunate facial resemblance to Mark Gastineau, the former New York Jets defensive end who wasn’t nearly as successful a boxer as he was at sacking quarterbacks – had much of life still to live when, on Sept. 23, 2012, he died at 46, a day after being shot by robbers at a restaurant in Brits, South Africa, to celebrate a family member’s 21st birthday. He died a hero, trying to shield his teenage daughter, Marinique, during the premeditated attack.

Three Zimbabweans, all in their early 20s and first offenders, were convicted of murder, armed robbery and possession of unlicensed firearms and ammunition. Each is serving what is tantamount to a 30-year sentence, a penalty not seemingly in keeping with the seriousness of the crimes committed.

“The loss against him changed a side of my character tremendously. It made me tougher and it made me better,” Wlad said upon being informed of Sanders’ death. “Without my experience with Corrie I wouldn’t be the same way.

“The boxing world will remember Corrie as a heavy hitter and a good man. I have nothing bad to say about Corrie at all.”

Was Corrie Sanders a one-hit wonder? Not really. Before his rout of Wlad, he had wins over such recognizable names as Johnny DuPlooy, Al “Ice” Cole, Bobby Czyz, Carlos De Leon and Bert Cooper. Would his status in global boxing been more established had he not been so intent on fighting primarily in South Africa, instead of moving to the United States as had been the case with several of his countrymen, like Botha? Probably. But home is where the heart is, and Corrie Sanders’ heart was forever anchored in the nation of his birth.

“Maybe I loved my country too much,” he once said.

Can’t fault a man for that.

Bernard Fernandez retired in 2012 after a 43-year career as a newspaper sports writer, the last 28 years with the Philadelphia Daily News. A former five-term president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, Fernandez won the BWAA’s Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism in 1998 and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service in 2005. On Jun 14, 2020, New Orleans native Fernandez — who now writes exclusively for The Sweet Science — will be formally inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision