Featured Articles

The Top Ten Super-Middleweights of the Decade: 2010-2019

The Top Ten Super-Middleweights of the Decade: 2010-2019

Super-middleweight offers a surprisingly shallow decadal well with a top two written in stone, no defined number ten and a fuzzy nine through six, although, as always, meetings between some of those fighters helped straighten a few things out.

That the 168lb Super Six tournament, the inaugural super series, was mid-flow on January 1st 2010 means that not all of those results are considered, which hits some harder than others. It took some time for a new generation to traverse the rubble left behind by the monstrous divisional number one and two, but when they did they flooded the top five, usurping men like Mikkel Kessler who left the best part of his career behind in the 00s.

The picture is complicated and often the differences between fighters are small but it made for a fascinating if under-whelming 168lb decade.

10 – David Benavidez

Peak Ranking: 2 Record for the Decade: 22-0 Ranked For: 32% of the Decade

A surprising inclusion, David Benavidez makes it in at ten based, in all honesty, upon the total absence of an outstanding candidate.

Lucian Bute was the early runner, and at the dawn of the decade it would have been hard to imagine him not making a list like this; a final paper record for the decade of 7-5 all but excludes him though and his best win being over a collapsing Glen Johnson is the final nail in that particular fistic coffin. Andre Dirrell ran him close but actually achieved surprisingly little between his controversial 2009 loss to Froch and his 2015 defeat to James DeGale. It’s not clear-cut, but Benavidez is the right choice.

He survived a startling gut-check in 2017 when dropped by Romanian tough Ronald Gavril in the final frame of his first twelve round contest in a fight he won by the narrowest of margins. Benavidez proved the value of such lessons in an immediate rematch, winning almost every round in a near-shutout of high caliber.

As 2019 came to an end and with this list (then only thought of) completely bereft of a tenth entry, Benavidez stopped Anthony Dirrell, then the number four contender, to seal the low spot. It was an impressive performance as he out-hustled and out-jabbed a faster-handed fighter, a layered offense built of two-handed attacks to body and head barracking severe pressure. Benavidez has a bright future, here he is lauded for his fledgling past.

09 – Arthur Abraham

Peak Ranking: 1 Record for the Decade: 16-6 Ranked For: 66% of the Decade

Arthur Abraham lost majority of his big fights in the 2010s; by disqualification to Andre Dirrell; by shutout against Carl Froch; by outclass against Andre Ward: even against elite prospects once he had limped past his prime.

The two things that speak for him here are his dogged commitment to the weight-class, which he inhabited from 2010 until his retirement in 2018 and his series victory over Robert Stieglitz. Stieglitz, himself a contender himself for this list, was a highly ranked and formidable fighter who prioritized a regional rivalry with Abraham above all other things. Abraham, out of Armenia, had relocated to Germany, just as Stieglitz had done from Russia; the German yard seemed big enough for only one super-middleweight.

Abraham puts me in mind of a less dangerous Huck, which is perhaps damning with faint praise. Nevertheless, it is hard not to see the similarities in the first fight between Abraham and Stieglitz as Abraham overcame a relative paucity of activity to surge from the ropes and win key sections of key rounds and a narrow decision. The fight was so close (I scored it a draw) that a rematch was inevitable, and Abraham lost that rematch, his left eye closed by an unerring Stieglitz right hand which saw him stopped in three one-sided and foul-filled rounds. In the third fight, by which time Stieglitz was being favored, the men were sharing a purse of over $3m; Abraham, viewed, perhaps, as sliding, was as good in the second half of this fight as he had ever been. In a chaotic, filthy match his punching was consistently cleaner, his footwork markedly better even in the exhausted twelfth round in which he received a beating for more than two minutes before countering with a gorgeous uppercut to seal the victory with a knockdown. In the fourth and final fight, Abraham was at last able to see off his great rival in a sixth-round stoppage.

This series is the bedrock of Abraham’s ranking in the 10s, his biggest wins over Jermaine Taylor and Edison Miranda all coming in the 00s.

08 – Gilberto Ramirez

Peak Ranking: 2 Record for the Decade: 34-0 Ranked For: 49% of the Decade

The inclusion here of Gilberto Ramirez may raise some eyebrows but in truth, leaving him out is next to impossible. He defeated Arthur Abraham after all, and so clinically that only Andre Ward and perhaps Carl Froch can claim to have matched him.

What most impressed me about Ramirez, who fought Abraham on the undercard of the Manny-Pacquiao-Timothy Bradley rematch from 2016, was how he handled the veteran’s tempo. Abraham had been fighting at title level for as long as Ramirez had been fighting and he ceded the tempo of the fight to the younger man early, allowing him to force the pace. Ramirez eschewed the classic mistake of pushing too hard. He accepted responsibility as the general and then boxed at his own steady rate, deploying a beautiful right hook to the body, moving well but not excessively, jabbing the Abraham high guard to keep him occupied, finding what gaps there were.

It was a beautiful performance.

Abraham, it might be argued, was past prime – it is worth reminding the reader though that he had just turned in two of his career’s best in 2014 and 2015 against Stieglitz. That was the Abraham Ramirez faced.

Ramirez spent almost the entire decade fighting at the poundage and his raw numbers are impressive. It’s jarring to see him at number eight, and perhaps revealing of 168lbs strength in depth, but he’s unquestionably a special fighter and arguably has the best signature win of anyone outside the top six.

A quick word for Andre Dirrell, who also holds a win over Abraham from 2010 but doesn’t make the list. Fairly or unfairly (and it’s unfair as Dirrell was clearly winning the fight at the time of the stoppage), a victory by disqualification is less impressive than a wide UD, so Dirrell misses out.

07 – James DeGale

Peak Ranking: 1 Record for the Decade: 20-3-1 Ranked For: 56% of the Decade

The most instructive fight of James DeGale’s career, and perhaps his best, is his 2015 points victory over Andre Dirrell. DeGale, slightly out-sped, was clearly uncomfortable in the very early moments of the round, Dirrell’s quick jab and a gorgeous counter-uppercut giving him pause for thought. A beautiful left hand from a stance neither southpaw nor orthodox but somewhere in between (DeGale switched), changed the direction the fight seemed to be taking. DeGale took over.

Then, in the seventh, he gassed. It was clear and it was sad, a fighter gone from close control fostered by deep combinations to walking in wide circles with low hands, pot-shotting. He clearly lost the seventh, eighth, ninth and then the tenth. It made his heart-fuelled rally in the eleventh and twelfth all the more thrilling.

A Rolls-Royce with a scooter’s gas-tank, DeGale’s great flaw made him a much more interesting fighter, drawing him into thrillers where a man of his talents probably would otherwise have coasted. It cost him dearly in legacy, however – every blip on DeGale’s record owes something to his stamina issues.

Dirrell was clearly his best win and to be frank it is troubling to me that his second is likely Caleb Truax – but Truax was only highly ranked as a super-middleweight because he had previously beaten DeGale in one of his most pronounced fades; he was barely able to avoid a repeat in the rematch.

That said, he could have taken a victory in his hairline defeat to early nemesis George Groves, sending him off on a different trajectory. Having looked carefully at him here, however, I’m struck by the idea that given his very real limitations, DeGale squeezed almost everything he could have from his rather fascinating career.

06 – Mikkel Kessler

Peak Ranking: 2 Record for the Decade: 4-1 Ranked For: 38% of the Decade

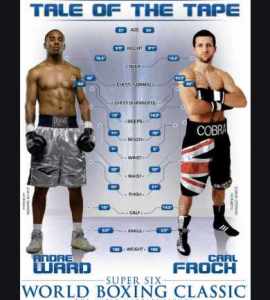

At first I thought Kessler’s decadal legacy may be the weakest of all the divisional number sixes we will run into. A wonderful fighter, he threw punches in anger just five times at the beginning of the decade and never ranked higher than #2. His inclusion here stands upon what is likely the single best 168lb performance of the decade not executed by Andre Ward, the April 2010 clash between he and Carl Froch.

Prime Kessler was such a rare sight. No fighter of the era struggled so desperately with injuries – back, eye, and especially elbow troubles tormented him; but on that April night in Denmark you saw the closest thing we ever saw to Kesslerian perfection.

Not that he had it all his own way; the fight was thrilling, brutal, accompanied by some horrible facial injuries and some violent punches. Technically superior to Froch and sporting arguably the best traditional one-two punch in the sport at that time, Kessler survived one of Froch’s patented late surges to pull out the final rounds on my card and win a desperately narrow decision. It was a thing of savage beauty.

He lost the rematch but in between did some fine work, including an unprecedented three round destruction of Brian Magee and a crushing knockout of super-six competitor Allan Green. So on second thoughts, Kessler is just about good for this spot, not an outstanding number six but probably not a problematic one.

05 – George Groves

Peak Ranking: 1 Record for the Decade: 21-4 Ranked For: 77% of the Decade

When George Groves met James DeGale in 2011 their combined record was 22-0, prospects foolishly but gloriously jumping the gun to settle a domestic rivalry that hadn’t even had the proper time to coagulate.

DeGale was favored; Groves won, a fascinating and tension-filled combat, unexpectedly boxing off the back foot to out-squabble and counter his way to the narrowest of victories. It was not undisputed by ringsiders.

Groves and DeGale never met again and their respective careers plunged in and out of the choppy 168lbs waters, now one pre-eminent, now the other. Both achieved the number one contender’s spot, both won straps, neither lifted the undisputed, legitimate championship of the world and here, in the end, I have Groves edging him out in terms of legacy.

Groves made his mark, but he did it the hard way, with grit, gumption, heart and nerve. People forget how close he was to retirement after his loss to Badou Jack and how much his status within the fight game was propped up by his two exciting losses to Carl Froch. Exciting losses are fine, perhaps, for gathering cash but are worth very little in the cold eyes of history.

It was important for Groves to carry on after the loss to Jack because his two most important wins, over Martin Murray and Chris Eubank, came after that night. This hardly makes for an impenetrable top-five resume for the decade, but as we’ve seen, competition is a little sparse and so his determination to fight on where so many may have slung in the towel scrambles him over the line.

04 – Callum Smith

Peak Ranking: Ch Record for the Decade: 27-0 Ranked For: 38% of the Decade

So, Groves becomes the gatekeeper to the decade’s true elite. Numbers four, three and two all defeated him and for each of them he was a win of major importance, none more so than Callum Smith.

This is true for two reasons. Firstly, Groves was nothing less than the world’s number one contender, and with no true champion on the throne, the most important fighter at the poundage. For all that he was sliding, he had also summitted. The man to knock him off his perch was always going to benefit, and that man was Smith.

Secondly, Smith only arrived as a major force taking significant scalps at the decade’s end. The Groves fight, in 2018, was his first of any true global significance. After this he mercilessly buried contender Hassan N’Dam N’Jikam in just three rounds before running into the diminutive John Ryder where he was arguably lucky to get a unanimous nod in a close fight.

Against Groves though, he had been dominating, imperious. Groves, who scored his two most meaningful career wins in the previous eighteen months, had only ever been stopped by Carl Froch, but this was something else again. There was a sense of overlapping generations, even eras, as Smith, who looked bigger, stronger, flat-out healthier, faster and more powerful, countered and battered Groves around the ring. It felt like the emergence of someone a little special.

His shaky performance against Ryder has since cast doubt upon that perception, but not upon his placement here. Smith is locked into the top five.

03 – Badou Jack

Peak Ranking: 2 Record for the Decade: 18-3-3 Ranked For: 48% of the Decade

Badou Jack’s 168lb career is fascinating and scoring his cornerstone fights is fascinating. Jack met Anthony Dirrell (W, MD), George Groves (W, SD), Lucian Bute (Draw, later changed to a DQ after Bute tested positive for drugs) and James DeGale (D). All fights that were called controversial for one source of another and all back to back. We don’t have the space here to deep-dive each but a brief summary is called for.

His fascinating tussle with Dirrell is one of my favorite lo-fi combats of the decade and sees Jack slowly take over from his more highly ranked opponent, finally going to work on him on the ropes to take a justified decision in a fight that seemed at times contested in the proverbial phone-booth, yet somehow rambled across the whole ring. Against Groves, in another fine fight, Jack started faster, scoring a knockdown with a pair of flashing right hands in the first, and finished the stronger, rattling his man with that same punch in the twelfth. Once more, the fight was close, but the scoring was justifiable. Against Bute, Jack was unlucky to see the official scorecards a draw, but this wrong was righted when Bute was unfortunately busted for performance enhancing drugs, the fight now listed a win for Jack. Finally, against DeGale, a justifiable draw was rendered, but given that he threw more punches and landed at a higher rate and came reasonably close to a stoppage in the twelfth, he can probably count himself a little unlucky here.

Jack’s appearance at number three may be unexpected to some, but it shouldn’t be. He mixed it at the highest level and for the most part he came off best. His single loss at the weight, a bizarre first round defeat to the little-known Derek Edwards should arguably relegate him to the fourth spot, but Smith arrived just one fight too late to overhaul him for me.

02 – Carl Froch

Peak Ranking: 1 Record for the Decade: 7-2 Ranked For: 50% of the Decade

I did no analysis at all before installing Carl Froch at number two and I’m glad that this decision has been borne out by the review. Nobody came close to usurping him and the gap between two and three is probably bigger than the gap between three and nine.

Froch lost twice. In 2011, he was outclassed by one of the best super-middleweights in history, our number one, and the year before he was pipped by Mikkel Kessler in a thriller. The rematch, too, would be thrilling and is among the most fascinating I have seen in terms of adjustment and counter-adjustment deciding the outcome. Froch was “basic” according to Antonio Tarver and so many others, but in fact he was layered and thoughtful. If the Kessler performance doesn’t persuade you, the Arthur Abraham one certainly will. Froch turned pure-boxer that night, in his ungainly way, to all but shut Abraham out on the cards. Whether he was throwing over a thousand punches (Kessler II) or fighting in staged raids against a supposedly superior opponent (Lucian Bute), Froch tended to find a way to win.

And he did so against a glorious level of opposition, taking more ranked scalps than anyone on this list outside of Ward while actually doing slightly more damage to the top five. Froch squeezed every single drop out of his potential during a run (2008-2014) held to be the most difficult ever traversed by a British fighter. Had Andre Ward never been born, Froch would be the clear number one for the decade.

01 – Andre Ward

Peak Ranking: Ch. Record for the Decade: 11-0 Ranked For: 47% of the Decade

Andre Ward was born, however, and stands as a number one even more unassailable than Oleksandr Usyk who seemed so imperious at cruiserweight. In truth, he’s not that far ahead of Froch in terms of his 168lb resume, but the difference maker is his crushing victory over the divisional decadal number two, so one-sided as to be trivial.

Froch, who showed so many adaptions in his career, could do nothing with Ward. He tried the backfoot when Ward outfought him ring center, then he tried those two-handed surges that did so much damage against so many world class opponents. Ward was one step ahead of him at every turn, technically out-matching him with a left-hook stood against his high guard and also matching him for strength, so surprising for those who had not been paying attention; but Ward had done the same in out-classing Mikkel Kessler two years before and was never out-muscled in any fight I ever saw him in. A stinging rather than a hurtful puncher, he was otherwise as complete a fighter as walked the earth.

Why, it was often asked, did nobody just rush him? Ultra-aggressive fighters like Sakio Bika, Arthur Abraham and Froch, why didn’t they just try to boom through him and make him pay? And the answer is that it was really, really hard. Froch got in and threw body punches and tried to rough his man up and was consistently out-fought and out-mauled, it was Ward, not Froch who won these spells. Abraham ended up stacked behind his ear-muffs, being savagely punished to the body. Allan Green, Chad Dawson, Edwin Rodriguez, they all had plans and they all failed utterly.

“I’m bitterly disappointed,” said Froch after Ward demoted him to the era’s number two for all time. “He’s a very tricky, very slick very awkward…very good fighter. Credit to Andre Ward.”

Every man who ever faced Andre Ward ended up similarly disappointed. His was an understated reign of terror. The man brooked no resistance.

Photo credit: Tom Casino / SHOWTIME

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival