Featured Articles

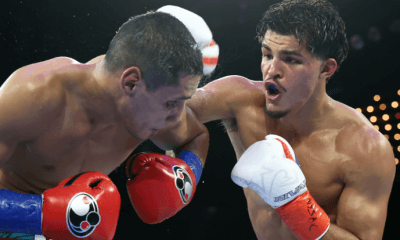

The Remarkable Career of “Ferocious” Fernando Vargas

The Remarkable Career of “Ferocious” Fernando Vargas

Back in the 90s the sport of prizefighting in Southern California was centered in the major cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego.

Along came a small group of aspiring boxers including a fiery youngster named Fernando Vargas who hailed from Oxnard, California.

“Top of the food chain baby!” was the rallying cry of Vargas and others.

Vargas simply stood out among the others from the farming community of Oxnard. He quickly rose up the ranks in a weight division not common for Mexican-Americans and became an Olympian and later a super welterweight world champion as a pro.

He also was tabbed by the nickname “Ferocious” Fernando Vargas, a moniker he earned throughout his boxing career. Last week the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame added Vargas name to their honored list.

“It’s a tremendous honor,” Vargas said.

When he was a youngster in junior high he admitted to having a quick-trigger when it came to unleashing those quick fists.

“I wasn’t a bully but if somebody wanted something I wouldn’t hesitate,” said Vargas via phone in Las Vegas.

After a junior high suspension, he was forced to stay home and by accident, or serendipity, the fiery youngster happened to see a TV news clip of youngsters boxing in Oxnard. He didn’t know fighting was allowed or even practiced. He wanted to be a part of it so he hunted it down and discovered the gym three miles away from his home.

“I walked there every day three miles,” said Vargas. “I never missed a day.”

The fighter quickly became part of the Garcia clan that was sparking interest in Oxnard boxing. The head of the family, Eduardo Garcia, quickly became the father figure of Vargas and taught him the rudiments of boxing.

“He’s my jefe and will always be my jefe,” said Vargas. “He has always been like a father to me.”

La Colonia Gym

It was either 1993 or 1994 when a Los Angeles Times reporter was sent to investigate a boxing club that was making noise in Southern California. It was unusual to hear that several boxers from the Ventura County area were slicing through boxing competition in the amateur levels. One boxer, Robert Garcia, was considered a prize prospect in the professional ranks and had been signed by Top Rank promotions.

While interviewing Garcia, the reporter was urged to talk to a youngster, Fernando Vargas, who was blowing by competition in the amateurs. It was the first time I met him; he was about 16 years old at the time.

“He is really good, he’s going to do things,” said Garcia that day of Vargas.

We shook hands and Vargas resumed his training. There were about two dozen youngsters training outside because the new La Colonia Gym was being built.

By 1996, Vargas was making headway in the national amateur boxing scene and after fierce competition captured a position on the USA Olympic Boxing team. Though the Oxnard youngster did not win a medal in the Atlanta Olympics due to strange scoring, he was primed and ready for the professional ranks.

“We were always taught the pro style, not that pitty-pat stuff,” said Vargas. “We were taught to throw three and four-punch combinations and nothing more than that. Once in a while maybe five but all of our punches connected.”

It was that pro style that first enabled Robert Garcia to win the first world title by an Oxnard fighter in March 1998. Vargas soon followed by capturing the second world title by stoppage against Mexico’s Yory Boy Campas in December 1998. Vargas had just turned 21 years old. He was the youngest fighter to win a super welterweight title.

Campas was a revered Mexican warrior and the victory by Vargas sent shockwaves through the boxing community. But for Vargas his sweetest victory took place seven months later against Raul Marquez in the Lake Tahoe, Nevada.

“I was at my best against Raul Marquez. I don’t know how to describe it but I never felt better before a fight. Everything was working, even during training things were perfect. I made weight easy and felt good during that fight,” said Vargas. “I walked in there feeling I could not be beat. I felt invincible.”

He defeated Marquez by technical knockout in the 11th round and then out-battled Winky Wright to win by majority decision. At the time, few knew the abilities of Wright and a few skeptics arose doubting Vargas’ talent. In his next fight, the doubters would be silenced.

Bigger Game

One man feared in the welterweight and super welterweight division was Ghana’s human battering ram Ike “Bazooka” Quartey. He had just faced Oscar De La Hoya and lost a back and forth battle with the East L.A. fighter but had raised his profile as a dangerous foe for anyone.

Vargas accepted a fight with Quartey.

Instead of seeking easy opposition, the fiery Vargas sought out fights that his rapidly growing legion of fans preferred. Quartey fit that prerequisite perfectly. He was avoided, feared and had only lost once to a fighter widely respected. Vargas wanted that respect too.

A crowded arena at Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino awaited them on April 15, 2000. Fans for both packed the seats for the IBF super welterweight title clash in Las Vegas. The Oxnard fighter’s eagerness to prove his mettle quickly gained him admiration and a quickly growing legion of “El Feroz” rabid fans. The loud and boisterous Vargas fans arrived in droves and made their presence known.

But could Vargas defeat Quartey?

Though Vargas was known as a boxer-puncher he seemed to prefer slugging it out. All of those watching on television and those in the arena expected a battle of machismo, but instead Vargas showcased his polished ability to box and give angles against Quartey’s seek and destroy style. It also proved the Oxnard fighter was more than just a slugger, but a skilled warrior capable of sustaining a disciplined attack for 12 tense rounds. Vargas won by unanimous decision to the joy of his fans.

Parties erupted all over Las Vegas that night wherever fans of “El Feroz” gathered. In the coming weeks celebrations were still taking place including a planned bash in Montebello, California. Vargas and his crew arrived and the partying continued.

Vargas fans were drunk with pride at his victory. Who would be next?

Tito

One of the biggest names in boxing was Felix “Tito” Trinidad who had defeated De La Hoya by majority decision in September 1999 and followed that up by moving into the super welterweight division. Knockout wins over David Reid and Mamadou Thiam gained the popular Puerto Rican slugger the WBA super welterweight title. It was a perfect match for Vargas who held the IBF version.

Both champions met at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino on December 2, 2000 before a raucous packed arena. Puerto Rican and Mexican flags were scattered throughout the stands. Vargas fans were confident as were Trinidad’s.

Vargas, 22, was just days before turning 23 and was the natural super welterweight. Trinidad was 27-years-old and in his prime when he stepped in the boxing ring for their unification bash.

It was a horrible start for Vargas who was dropped twice before the first minute of the first round by Trinidad’s vaunted left hook. The Puerto Rican celebrated after the second knockdown thinking the fight was over. It was far from over, as Vargas showed that tremendous heart he was famous for.

“I came back and I knocked him down and he hit me in the balls. It was f****n crazy but I gave everything that I had in me and left everything in the ring,” said Vargas.

After six rounds the Oxnard fighter had managed to pull even with a furious and ferocious counter-attack including a knockdown of the Puerto Rican champion. It looked like Vargas had pulled out a miracle. But those knockdowns and the persistent attack by Trinidad saw the fight tip in his favor and in the 12th and final round Trinidad connected again with that lethal left hook and down went Vargas three more times before the fight was stopped. Trinidad had defeated Vargas.

“To this day I don’t even remember that fight after the first knockdown,” said Vargas. “My wife told me I had been knocked down five downs and I said what? I only remember one knockdown.”

Regardless of the loss Vargas remained a fan favorite because of his willingness to fight the best and do it with guts. Hardcore fight fans loved his style and throughout his career his fans remained loyal and devoted. He was a true warrior and for many boxing lovers that’s what prizefighting is all about.

Today, Vargas owns a gym in Las Vegas and has three sons competing in the amateur boxing program. All three sons are outstanding boxers and groomed to fight in a style similar to his own.

“I teach my sons to be able to fight a variety of styles and not be just one dimensional,” said Vargas whose sons are named Fernando Jr. Emiliano and Amado. “That’s how you get beat.”

At his gym called the Feroz Fight Factory in North Las Vegas, several dozen youngsters train regularly. It’s one of the premier gyms in the new Mecca of boxing Las Vegas.

Vargas was one of the primary reasons for the resurgence of boxing in not only Southern California but the entire southwestern region of the U.S. All fans of boxing remember “El Feroz.”

When the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame announced the selection of this year’s class of 2020 many fans applauded the choice of Fernando Vargas. The induction ceremony is scheduled to take place on August 7th and 8th at the Red Rock Casino in Las Vegas.

“Aw man, it was a blessing. I’m grateful I did some things in the sport to be inducted. I was humbled and to be enshrined with the likes of Roberto Duran, Mike Tyson, Thomas Hearns and Oscar De La Hoya is truly a blessing,” said Vargas.

And for those who forget Vargas and where he came from, just remember his war cry: “Top of the food chain. Oxnard stand up.”

Welcome Fernando Vargas to the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision