Featured Articles

Remembering Dr. Ferdie Pacheco as he Remembered Muhammad Ali

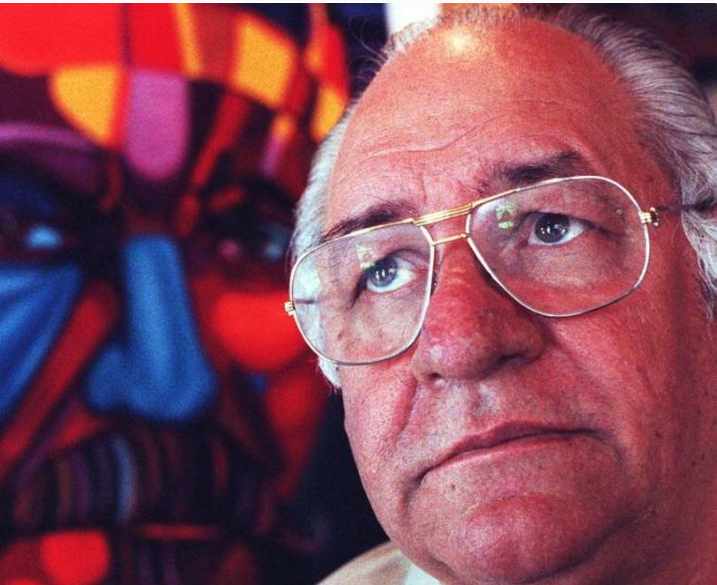

A TSS CLASSIC FROM THE THOMAS HAUSER ARCHIVE (2017) — Ferdie Pacheco, who died on November 16, was a doctor, author, artist, and television commentator. He’s best known for having been Muhammad Ali’s personal physician and cornerman from 1960 through 1977.

My own relationship with Pacheco began in 1989. I was researching the book that would eventually become Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times and had compiled a list of two hundred people I wanted to interview. Ferdie was among them.

During the course of my research, I encountered many people who had written or were contemplating writing about Ali. Some of them refused to talk with me about Ali, saying that we were competitors and they didn’t want me to steal their thunder. Others were extraordinarily generous with their time and knowledge. Ferdie fit into the latter category. Even though he’d written one Ali book and was planning another, he sat with me for hours.

In the years that followed, Ferdie remained one of my “go-to” guys when I wrote about Ali. Rather than interpret what he told me, I’ll let him speak for himself.

ON CASSIUS CLAY’S FORMATIVE YEARS IN MIAMI:

“Cassius was something in those days. He began training in Miami with Angelo Dundee. And Angelo put him in a den of iniquity called the Mary Elizabeth Hotel because Angelo is one of the most innocent men in the world and it was a cheap hotel. This place was full of pimps, thieves, and drug dealers. And here’s Cassius, who comes from a good home, and all of a sudden he’s involved with this circus of street people. At first, the hustlers thought he was just another guy to take to the cleaners, another guy to steal from, another guy to sell dope to, another guy to fix up with a girl. He had this incredible innocence about him, and usually that kind of person gets eaten alive in the ghetto. But then the hustlers all fell in love with him, like everybody does, and they started to feel protective of him. If someone tried to sell him a girl, the others would say, ‘Leave him alone; he’s not into that.’ If a guy came around, saying, ‘Have a drink,’ it was, ‘Shut up; he’s in training.’ But that’s the story of Ali’s life. He’s always been like a little kid, climbing out onto tree limbs, sawing them off behind him, and coming out okay.”

“When Ali was young, he was the best physical specimen I’ve ever seen. If God sat down to create the perfect body for a fighter, anatomically and physiologically, he’d have created Ali. Every test I did on him was a fine line of perfect. His blood pressure and pulse were like a snake. His speed and reflexes were unbelievable. His face was rounded, with no sharp edges to cut. And on top of that, his skin was tough. He could summon up enormous spurts of energy and recover quickly without the exhaustion that most fighters feel afterward. His peripheral vision was incredible. Up until the layoff, it was like a fraudulent representation to say I was Ali’s doctor. I was his doctor in case something happened, but it never did. Being Ali’s doctor meant I showed up at the gym once in a while and came to the fights.”

ON CLAY-LISTON I:

“Things in the dressing room got pretty bizarre. The only people who were supposed to be there were Cassius, Angelo, Rahaman (Clay’s brother), Bundini, myself, and Luis Sarria (Clay’s masseur). A few more came and went, but basically we were alone. Then Cassius assigned Rahaman to watch his water bottle. The bottle was taped shut. No one went near it. But every time Rahaman took his eyes off it, Cassius would take the tape off, empty it out, refill it, and tape it closed again. He did that three or four times because he was worried that someone would try to drug him. And he was particularly suspicious of Angelo, because Angelo was Italian. In his mind, he’d begun to associate Angelo with the gangsters around Liston. Remember, the Muslims—and it was clear by then that Cassius was a Muslim—had never been in boxing before. All they had to go by were Hollywood movies where the mob fixed everything, and Liston was with the mob. It was crazy, but that’s what Cassius thought.”

“All those bullshit boxing stories people write; pretty soon, everyone starts believing them. Angelo cut the gloves in the first Cooper fight. Bullshit. Sit him down, and he’ll tell you that the gloves were already split. He just helped them along a little. Angelo loosened the ropes for the Foreman fight in Zaire. Bullshit again. Angelo and Bobby Goodman tried to tighten the ropes right until the opening bell. Most of it’s nonsense. But one thing that truly belongs in the legend category was what went on between the fourth and fifth rounds of the Liston fight. Cassius couldn’t see. He was ready to quit. And it had nothing to do with lack of courage, because this was a kid who’d been fighting since he was twelve years old. He’d been poked and banged and busted and clobbered many times. He’d made his accommodation by then with the normal pains and blows of boxing. But this was something beyond what he’d experienced. I could see it. His eyes were aflame. And Angelo was spectacular. What he did between rounds was the best example I can give you of a cornerman seizing a situation and making it right. That moment belonged to Angelo. If Cassius had been with a corner of amateurs, there would never have been any Muhammad Ali.”

“Just going out for the fifth round was an incredibly brave thing to do. Liston was considered as destructive as Mike Tyson before Tyson got beat. And Cassius was absolutely brilliant then. The things he did, staying out of range, reaching out with his left hand, touching Liston when he got close to break Sonny’s concentration. It was an amazing, astonishing, breathtaking performance. Here’s a fighter who’s supposed to be Godzilla, who will reign for maybe a thousand years. Nobody can stand up to him in the ring. Cassius can’t see, and still Liston couldn’t do anything with him. What can I say? Beethoven wrote some of his greatest symphonies when he was deaf. Why couldn’t Cassius Clay fight when he was blind?”

ON ALI’S RETURN FROM EXILE:

“In the early days, he fought as though he had a glass jaw and was afraid to get hit. He had the hyper reflexes of a frightened man. He was so fast that you had the feeling, ‘This guy is scared to death; he can’t be that fast normally.’ Well, he wasn’t scared. He was fast beyond belief and smart. Then he went into exile. And when he came back, he couldn’t move like lightning anymore. Everyone wondered, ‘What happens now when he gets hit?’ That’s when we learned something else about him. That sissy-looking, soft-looking, beautiful-looking child-man was one of the toughest guys who ever lived.”

“The legs are the first thing to go in a fighter. And when Ali went into exile, he lost his legs. Before that, he’d been so fast, you couldn’t catch him so he’d never taken punches. He’d been knocked down by Henry Cooper and Sonny Banks. But the truth is, he rarely got hit and he’d never taken a beating. Then, after the layoff, his legs weren’t like they’d been before. And when he lost his legs, he lost his first line of defense. That was when he discovered something which was both very good and very bad. Very bad in that it led to the physical damage he suffered later in his career; very good in that it eventually got him back the championship. He discovered he could take a punch. Before the layoff, he wouldn’t let anyone touch him in the gym. Workouts consisted of Ali running and saying, ‘This guy can’t hit me.’ But afterward, when he couldn’t run that way anymore, he found he could dog it. He could run for a round and rest for a round, and let himself get punched against the ropes while he thought he was toughening his body. I can’t tell you how many times I told him and anyone else who’d listen, ‘Hey, when you let guys pound on your kidneys, it’s not doing the kidneys any good.’ The kidneys aren’t the best fighter in the world. They’re just kidneys. After a while, they’ll fall apart.’ And of course, taking shots to the head didn’t do much good either.”

ON ALI-FRAZIER I:

“In round fifteen, Ali was tired. He was hurt, just trying to get through the last round. And Frazier hit him flush on the jaw with the hardest left hook he’d ever thrown. Ali went down, and it looked like he was out cold. I didn’t think he could possibly get up. And not only did he get up; he was up almost as fast as he went down. It was incredible. Not only could he take a punch; that night, he was the most courageous fighter I’ve ever seen. He was going to get up if he was dead. If Frazier had killed him, he’d have gotten up.”

“Some fighters can’t handle defeat. They fly so high when they’re on top that a loss brings them irrevocably crashing down. What was interesting to me after the loss to Frazier was we’d seen this undefeatable guy. Now how was he going to handle defeat? Was he going to be a cry-baby? Was he going to be crushed? Well, what we found out was, this guy takes defeat like he takes victory. All he said was, ‘I’ll beat him next time.’”

ON ALI-NORTON I:

“The jaw was broken in the second round. Ali could move the bone with his tongue and I felt the separation with my fingertips at the end of the second round. That’s when winning took priority over proper medical care. It’s sick. All of us – and I have to include myself in this – were consumed by the idea of winning that fight. When the bell rang, I was no longer a doctor; I was a second. My whole thing was to keep Ali fighting. As a doctor, I should have said, ‘Stop the fight.’ There’s no disgrace in having a broken jaw. It goes down as a TKO; in six months you have a rematch and life goes on. But at that point in Ali’s career, he couldn’t afford a loss. And with Ali, there was always politics involved. We didn’t fight in a sterile atmosphere. We didn’t fight in a room closed off from the rest of the world. Everything had to do with Muslims and Vietnam and civil rights. If Ali lost, it was more than a fight. So you didn’t just have a white guy say, ‘Stop the fight.’ Especially if Ali didn’t want it stopped. And when we told Ali his jaw was probably broken, he said, ‘I don’t want it stopped.’ He’s an incredibly gritty son-of-a-bitch. The pain must have been awful. He couldn’t fight his fight because he had to protect his jaw. And still, he fought the whole twelve rounds. God Almighty, was that guy tough. Sometimes people didn’t realize it because of his soft generous ways. But underneath all that beauty, there was an ugly Teamsters Union trucker at work.”

ON ZAIRE:

“What Ali did in the ring that night was truly inspired. The layoff had taken away his first set of gifts, so in Zaire he developed another. The man had the greatest chin in the history of the heavyweight division. He could think creatively and clearly with bombs flying around him. And he showed it all when it mattered most that night with the most amazing performance I’ve ever seen. Somehow, early in the fight, Ali figured out that the way to beat George Foreman was to let Foreman hit him. Now that’s some game plan. Watching that fight, seeing Ali take punch after punch and knowing that, with his strength and courage, he wouldn’t go down, a person could have been forgiven for thinking that sooner or later the referee would be forced to step in to save his life. But Ali took everything Foreman could offer. And at that most crucial moment in his career, instead of losing, which was what most people thought would happen, he knocked George out and embarked on another long wondrous championship ride.”

ON ALI-FRAZIER III:

“You have to understand the premise behind that fight. The first fight was life and death, and Frazier won. Second fight; Ali figures him out, no problem, relatively easy victory for Ali. Then Ali beats Foreman and Frazier’s sun sets. And I don’t care what anyone says now; all of us thought that Joe Frazier was shot. We all thought that this was going to be an easy fight. Ali comes out, dances around, and knocks him out in eight or nine rounds. That’s what we figured. And you know what happened in that fight. Ali took a beating like you’d never believe anyone could take. When he said afterward that it was the closest thing he’d ever known to death – let me tell you something; if dying is that hard, I’d hate to see it coming. But Frazier took the same beating. And in the fourteenth round, Ali just about took his head off. I was cringing. The heat was awesome. Both men were dehydrated. The place was like a time-bomb. I thought we were close to a fatality. It was a terrible moment. And then Joe Frazier’s corner stopped it.”

“It all progresses in a fighter’s life. The legs go; his reflexes aren’t what they used to be; he cuts more easily; the injuries accelerate. Ali at age twenty-three could have absorbed Frazier in Manila and shaken it off. But age thirty-three was another story. If I had to pick a spot to tell him, ‘You’ve got all your marbles but don’t go on anymore,’ no question, it would have been after Manila. That’s when it really started to fall apart. He began to take beatings, not just in fights but in the gym. Even sparring, he’d do the rope-a-dope because he couldn’t avoid punches the way he did when he was young. And I don’t care how good you are at rope-a-doping. If you block ninety-five punches out of a hundred, the other five are getting in.”

ON ALI-SHAVERS:

“The Shavers fight was the final straw for me. After that fight, Dr. Nardiello, who was with the New York State Athletic Commission, gave me a laboratory report that showed Ali’s kidneys were falling apart. Instead of filtering out blood and turning it to urine, pure blood was going through. That was bad news for the kidneys. And since everything in the body is interconnected, we were talking about the disintegration of Ali’s health. So I went back to my office in Miami, sat down, and wrote Ali a letter saying his kidneys were falling apart. I attached a copy of Nardiello’s report and mailed three extra copies, return receipt requested. One to Herbert, one to Angelo, and one to Veronica, who at the time was Ali’s wife. I didn’t get an answer from any of them; not one response. That’s when I decided enough was enough. Whether or not they wanted me, I didn’t want to be part of what was going on anymore. By then, they were talking about ‘only easy fights.’ But there was no such thing as an easy fight anymore.”

ON ALI-HOLMES

“Just because a man can pass a physical examination doesn’t mean he should be fighting in a prize ring. That shouldn’t be a hard concept to grasp. Most trainers can tell you better than any neurologist in the world when a fighter is shot. You watch your fighter’s career from the time he’s a young man. You watch him develop into a champion. You watch him get great. Then all of a sudden, he doesn’t have it anymore. Give him a neurological examination at that point and you’ll find nothing wrong. Sugar Ray Robinson could pass every exam in the world at age forty-four, but he wasn’t Sugar Ray Robinson anymore. It doesn’t change, whether it’s Ali, Joe Louis. Anybody in the gym can see it before the doctors can because the doctors, good doctors, are judging these fighters by the standards of ordinary people and the demands of ordinary jobs. And you can’t do that because these are professional fighters.

AND IN SUMMARY:

“I look back at it all and consider myself a very lucky guy.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – A Dangerous Journey: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. He will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the Class of 2020.

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared on these pages on Nov. 16, 2017, under the title “Dr. Ferdie Pacheco: December 8, 1927 – November 16, 2017.” Reprinted with permission.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles1 day ago

Featured Articles1 day agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden