Featured Articles

Pete Hamill Was So Much More Than a Boxing Writer

Pete Hamill was one of my heroes. It pains me to write that the legendary journalist died today, Aug. 5, at age 85.

Hamill grew up in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, the oldest of seven children of an immigrant from Belfast who lost a leg to an injury suffered in a semi-pro soccer game. Like much of gentrified Brooklyn, Park Slope is a trendy neighborhood, but that certainly wasn’t true during Hamill’s boyhood when the air was ripe with the scent of the heavily polluted Gowanus Canal.

In one of his early non-fiction books, Hamill recollected the time during his adolescence when he called an acquaintance a kike while the Hamill family was gathered around the dinner table. This angered his father who reached over and slapped him. “Benny Leonard was a kike,” snarled the elder Hamill, referencing the esteemed 1920s-era lightweight champion. Awkward language aside, the old man was teaching his son something about the importance of respecting people of all backgrounds – and indirectly something about the nobility of prizefighters.

Hamill would write that in his blue-collar Brooklyn neighborhood in the years after World War II, there were only two sports that mattered: baseball and boxing. The institutions in his community, he wrote, were the factory, the church, the police station, the saloon, and the boxing gym. “There were fights in old dance halls, in bankrupt skating rinks, in National Guard armories, all of them serving as farm clubs for the big arena: Madison Square Garden.”

In his teens, Hamill took to hanging around boxing gyms. He befriended Jose Torres (pictured with Hamill in their later years) before Torres turned pro. Once he became established as a journalist, Hamill encouraged Jose’s literary ambitions and Torres, who won the world light heavyweight title under the tutelage of Cus D’Amato, went on to become a writer of considerable repute, “Boxing’s Renaissance Man.”

In a 1996 piece for Esquire, Hamill wrote, “I came to believe that fighters themselves were among the best human beings I knew. They were mercifully free of the macho bull**** that stains so many professional athletes. They were gentle in a manly way.” But by then Hamill had become disillusioned with boxing, viewing it as a remnant of a less advanced age. The tipping point was a dinner he attended where everybody tried to avoid looking directly at the guest of honor, Muhammad Ali, whose tremors were so bad that he was unable to lift a piece of chicken to his mouth. But Hamill continued to turn up at some of the big fights.

A high school dropout, Hamill briefly occupied the top editor’s chair at New York’s two major dailies, the Post and the Daily News. His published works include ten novels, more than a hundred magazine stories, two memoirs (one of which, “Downtown: My Manhattan,” serves as an excellent travel guide for anyone visiting New York), and several teleplays including the boxing-themed “Flesh and Blood” which was adapted by CBS into a two-part, four-hour telecast with a young Denzell Washington in a supporting role.

I once had the privilege of having lunch with Pete Hamill. The invitation came from my friend Harvey Rothman, rest his soul. Harvey had been the entertainment director at Caesars Palace when the Miami mob ran the joint and was unceremoniously dumped and left to his own wiles when the mob was kicked out. Hamill was in town to research “The Neon Empire,” a crime drama about Las Vegas commissioned by Showtime. The three of us had lunch at Caesars Palace and, if memory serves, Pete and I covered the tab as Harvey’s comping privileges had been revoked.

At the time, I didn’t know much about Hamill. My only recollection of him was seeing him on the David Susskind Show, a TV talk show in New York that dealt with current affairs. I don’t remember much of what was said at our luncheon other than we reminisced about New Orleans where we had both hung our hat for a spell. He was disappointed to learn that Sidney’s News Stand on Decatur Street was gone and the property had morphed into a seedy liquor store.

I would later learn that we had much in common other than the fact we were both born in Brooklyn (I grew up on Long Island so I wasn’t an authentic Brooklynite). During our early teen years, we both discovered the world of books through the novels of James T. Farrell, the great Chicago writer (long out of vogue) whose masterwork was the “Studs Lonigan Trilogy.”

Pete and I met up again when I hosted a late-night sports talk radio show in the Sportsbook of the old Stardust Hotel. My guest that night was the fabled boxing press agent Harold Conrad (purportedly the inspiration for the Humphrey Bogart character in the movie “The Harder They Fall”), who was then working for Don King. To my great surprise, Conrad arrived with Pete Hamill. Harold was then in his seventies and his memory was starting to fail him. Hamill could foresee that there would be some pregnant moments during the show if I didn’t have someone else to bounce questions off.

When someone dies at a ripe old age, it’s normal to say that he led a full life. But it’s hard to imagine anyone leading a life as full as the life that Pete Hamill led.

He was there marching along and taking notes as Dr. Martin Luther King led a march from Memphis to Jackson. He was there in Belfast at the height of “the troubles.” He was there when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated and helped subdue the attacker. He was on assignment in lower Manhattan when terrorists took down the World Trade Center and then spent the next 11 days documenting the recovery efforts. He dated Shirley MacLaine and Jackie Onassis. And, of course, he was ringside for the Fight of the Century, the first meeting between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Writing for Harper’s Bazaar, he called it the most spectacular event in sports history and no one who was there that night would disagree.

Pete Hamill was Forrest Gump. At the moments that define the timeline of my generation, he was seemingly always there.

Pete Hamill is survived by his second wife, journalist Fukiko Aoki, two daughters and a grandson. His eldest daughter Deirdre, a travel photojournalist based in Arizona, worked for a brief time at the Las Vegas Sun where she honed her craft covering the club fights. Pete’s brother Denis Hamill, younger than Pete by 17 years, is also a noted journalist.

Hamill, who was suffering from diabetes and using a walker, died in his bed at New York Presbyterian / Brooklyn Methodist hospital where he had gone after breaking his hip in a fall. The hospital is located in Park Slope. The well-traveled Pete Hamill had come full circle.

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

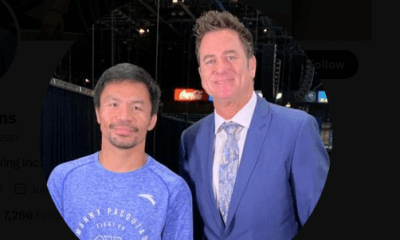

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons