Featured Articles

Boxing’s Chaotic Weight Divisions: A Short History of How We Got to Where We Are

The World Boxing Council recently created a new weight division. It’s called Bridgerweight and it’s for boxers weighing not less than 201 or more than 224 pounds.

The news fomented a firestorm of criticism. There are already too many weight classes yelped the belligerents. Adding yet another compounded the insult.

WBC president Mauricio Sulaiman could have forestalled the backlash — nay, he could have actually inverted it – if he had simultaneously done away with a couple of the weight classes near the bottom end of the spectrum. That’s what the National Boxing Association did in 1921. Ah, but we are getting ahead of ourselves.

In the bare-knuckle days, there were basically only three weight classes: heavyweight, middleweight, and lightweight. However, the ceilings for the two lower weight classes were not standardized, opening the door to multiple title claimants.

This situation persisted as the sport entered the modern era. Before World War I, the weight limit for featherweights in the United States was generally conceded to be 122 whereas the norm in Great Britain was 126. Likewise, the Brits defined a lightweight as 135 pounds whereas the Yanks held tight to 133. Eventually, the British nomenclature prevailed.

The original three weight classes eventually increased to seven and then to eight with the introduction of the light heavyweight division in 1903. The architect was Lou Houseman, the sporting editor of the Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper. Houseman managed Jack Root who had outgrown the middleweight class. When he matched Root against Kid McCoy, he billed it for the light heavyweight title. Fight writers were receptive and Root, who dominated McCoy en route to winning a 10-round decision, would enter the history books as the first light heavyweight champion.

An important development in the standardization of weight classes was the 1920 Antwerp Summer Olympics. Twelve nations sent boxers to these games, eight more than in 1908 when 32 of the 42 entrants — and all but one of the medal winners – were British. (There was no boxing at the 1912 games in Stockholm as the sport was outlawed in Sweden and the 1916 Olympiad was cancelled because of the war in Europe, so the 1920 games marked the return of boxing after a 12-year absence.)

The bouts at the 1920 Games were contested in eight weight divisions, up from five weight classes in 1908.

Flyweight (112)

Bantamweight (118)

Featherweight (126)

Lightweight (135)

Welterweight (147)

Middleweight (160)

Light heavyweight (175)

Heavyweight (176+)

These became the eight standard divisions, but it didn’t take long for a regulatory body to add new categories. The Walker Law of 1920, which had the effect of making New York the center of the boxing universe, included a provision for five additional weight classes: junior flyweight (109 pounds), junior bantamweight (118), junior featherweight (122), junior lightweight (130), and junior welterweight (140).

The first of these “junior” classes to make an appearance was the junior lightweight class. On Nov. 18, 1921, Tex Rickard presented a diamond-studded belt to Johnny Dundee after Dundee, the so-called Scotch Wop, defeated George “KO” Chaney at Madison Square Garden. (Chaney was disqualified in the fifth round for repeated low blows.)

On January 19, 1922, at the inaugural National Boxing Association convention in New Orleans, the junior lightweight and junior welterweight divisions were retained, but New York’s three other junior divisions were scrapped.

The sport already had a junior lightweight champion, Johnny Dundee, but New York hadn’t yet authorized a fight for the junior welterweight title so the NBA (the forerunner of the World Boxing Association, the first of the international governing bodies) got to go first. They bestowed the 140-pound title on Pinkey Mitchell, the less prominent of two fighting brothers from Milwaukee.

Strange but true. Mitchell was accorded this honor by winning an election, out-polling 19 other candidates in a survey conducted by the Boxing Blade, a Minneapolis boxing weekly. The magazine claimed that its readers returned more than 700,000 ballots. (Balderdash; boxing was big in those days, but it wasn’t quite that big.)

In due time, the junior lightweight title passed into the hands of Tod Morgan, a slick southpaw from Seattle. On Dec. 20, 1929, Morgan defended his belt against Benny Bass at Madison Square Garden. Bass knocked him out in the second round.

Benny Bass was nicknamed the “Little Fish” and this fight had the distinct aroma of rotten fish.

In the lobby of the Garden as the preliminaries were going on, bookies were quoting 6/1 odds on the challenger, a price that made no sense considering the reputations of the two fighters. The New York State Athletic Commission, which was then chaired by future U.S. Postmaster General James A. Farley, reacted by abolishing the junior lightweight division and for good measure, expunging all the other “junior” divisions as well.

The ruling did not impact any of the NYSAC-certified title-holders other than Bass as the commission hadn’t yet authorized any title fights in the three lowest junior classes and the junior lightweight title was vacant, having been abandoned by Johnny Dundee who went to win the more prestigious featherweight belt.

So, now we were back to only “8’ weight classes in New York whose boxing commission exerted considerable sway on the national scene when Massachusetts and Pennsylvania became aligned with it.

The junior lightweight class became dormant during the early years of the Depression and wasn’t revived until 1949 when the NBA sanctioned a match between Sandy Saddler and Orlando Zulueta for the vacant belt. Saddler, who had lost the featherweight title in his second meeting with Willie Pep, outpointed Zulueta in a dull 10-round fight at Cleveland to claim the vacant title.

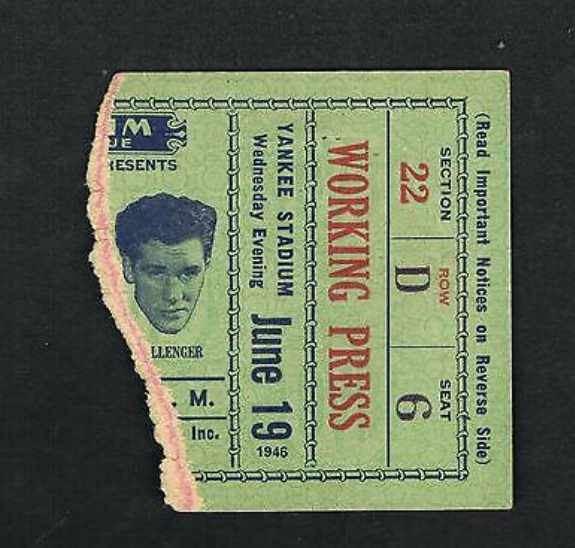

The NBA junior welterweight class went dormant in 1946 when Tippy Larkin abandoned the belt because he could no longer make the weight. It was revived in 1959. Carlos Ortiz began a new line of junior welterweight title-holders when he stopped Kenny Lane on cuts. By then the NBA had morphed into the World Boxing Association.

The New York commission refused to sanction the Ortiz-Lane match as a world title fight although the bout was held at Madison Square Garden, but eventually relented. It mattered greatly that Carlos Ortiz was a New Yorker. A Puerto Rican by birth, he resided in the Bronx. But by then it really made no difference whether New York recognized the junior welterweight division or not. In terms of national influence, the Empire State no longer had much clout.

Over the years, there has been pressure to raise the weight limits of the standard weight classes. This was considered preferable to cluttering up the landscape with more divisions.

In 1946, the NBA, at their annual convention, considered a motion to raise the limit of each weight class from 3-5 pounds. The flyweight division, for example, would go from 112 to 115; the middleweight division from 160 to 165. The motion was prodded by a Harvard study that showed that the school’s freshmen, on average, weighed 10 pounds more than their counterparts in 1892.

The motion never advanced to the voting stage, and this would be true again in 1953 after a government study revealed that the average American man of draft age was 10 pounds heavier than the average American soldier in World War I.

Prior to this, there was talk of raising the light heavyweight limit from 175 to 185 pounds. The impetus was Billy Conn’s feeble effort in his highly-anticipated rematch with Joe Louis. Conn came in at 182, twenty-five pounds less than the Brown Bomber. In theory, the match would not have been approved if the ceiling for light heavyweights had been set at 185 pounds.

Needless to say, none of these campaigns to raise the limits of the various weight classes succeeded. The weights of the eight classic divisions haven’t been disturbed in well over 100 years, notwithstanding the fact that people in most parts of the world and particularly in the Westernized world have, on average, become bigger, both taller and heavier.

Amateur boxing hasn’t been as hidebound. That’s a story for another day.

To be continued…….

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival