Featured Articles

Evander Holyfield’s Las Vegas Episodes (Part Two)

Seven weeks after announcing his retirement, Evander Holyfield had an about-face. The impetus was a two-day rally he attended in Philadelphia led by controversial televangelist Benny Hinn. During the services, Hinn “touched” Holyfield and pronounced him healed.

The reaction in the boxing community was overwhelmingly sarcastic. “I have a bum knee,” said New York State Athletic Commission chairman Randy Gordon, “that I would like (the faith healer) to look at.” But the wisecracks ceased when Holyfield went to the Mayo Clinic and the doctors there found no evidence of the heart defect. Evander had been misdiagnosed, or the problem had corrected itself organically, or – as Evander chose to believe – he had received a gift from God.

Evander began his comeback in Atlantic City in a 10-round contest with rugged Ray Mercer. Holyfield dominated Mercer in the late rounds, assuaging concerns about his stamina, and won a unanimous decision. Holyfield was too cheap to pay for a cut man (his trainer Don Turner assumed the responsibility), and it almost cost him when he suffered a bad cut over his right eye, but his triumph thrust him back in the heavyweight picture and set the wheels in motion for a rubber match with Riddick Bowe.

Bowe had never been knocked down until Holyfield knocked him to the canvas with a left hook in round six of the rubber match. But by then, Holyfield, out-weighed by 27 pounds, was “bone-tired.” Bowe stopped him two rounds later, reducing Evander’s record to 31-3. Interestingly, this was a non-title fight. Following his loss to Evander in their middle fight, Bowe had gone on to win the lightly-regarded WBO belt, but the promoter refused to pony up a sanctioning fee so no title was at stake.

Holyfield got back on the winning track in his next start, a match with Bobby Czyz at Madison Square Garden, Evander’s first appearance in the Big Apple since his pro debut 11-and-a-half years earlier. This was nothing more than a stay-busy fight. Czyz, 34, had won titles at 175 and 190, but he had begun his pro career as a middleweight and at 5’10” would be the shorter man by four-and-a-half inches.

Czyz retired on his stool after five rounds complaining of a foreign substance in his eyes. Holyfield was comfortably ahead when the bout ended, but he wasn’t impressive.

When it became known that Holyfield had landed a bout with Mike Tyson, it was immediately decried as a mismatch. Evander’s best years were behind him, or so it seemed, whereas Iron Mike had looked like his old self after returning from prison, scoring four fast knockouts while picking up the IBF and WBA belts along the way. In a poll of sportswriters by the Las Vegas Review-Journal, 47 of 48 respondents picked Tyson. (The apostate was Ron Borges of the Boston Globe who reversed course after originally picking Tyson by KO in a Boxing Illustrated survey.)

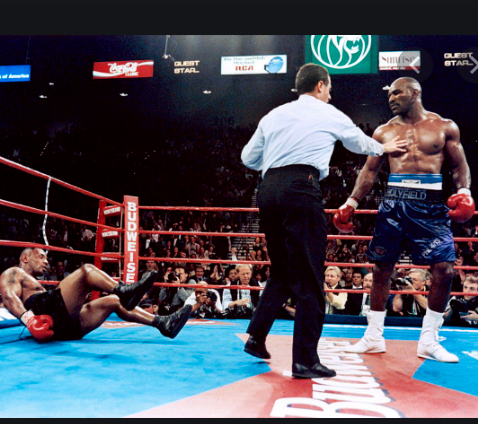

The Nevada Commission would not approve the fight until Holyfield underwent a more extensive battery of medical tests than he had received at the Mayo Clinic. Their qualms factored into the odds. The Las Vegas bookmakers opened Tyson a 25/1 favorite and suffered a bloodbath when Holyfield was victorious, stopping Iron Mike in the 11th round before a sell-out crowd at the MGM Grand Garden in a fight that had turned sharply in his favor. With the victory, Evander joined Muhammad Ali as a three-time heavyweight champion.

The rematch, also at the MGM Grand, was the infamous “bite fight,” a fight that has been hashed-over at length and won’t be re-hashed again here. Holyfield’s ears were an expensive comestible for Tyson who was fined three million dollars by the commission for his rampage.

Before the year was out, Holyfield renewed acquaintances with Michael Moorer. They met at the Thomas and Mack Center on the UNLV campus on Nov. 8, 1997.

Moorer, who no longer had Teddy Atlas in his corner, came in at a puffy 223 pounds, nine pounds more than in their first meeting. His recent efforts, although victorious, were lackadaisical and Evander, the would-be avenger, was installed the favorite.

Moorer looked good in the early-going and was winning the fifth until Evander knocked him down in the waning seconds of the round. Holyfield would knock him down twice more in the seventh and twice more in the eighth before the bout was halted on the advice of the ringside physician. This redemptive victory, coupled with his earlier triumph over Tyson, earned Evander The Ring’s Fighter of the Year Award, his third, a number surpassed by only Joe Louis (4) and Muhammad Ali (6).

All three significant belts were at stake when Holyfield squared off with Lennox Lewis at Madison Square Garden on March 13, 1999. This was the first “true” (unified) heavyweight title fight in a New York ring since the 1971 Fight of the Century between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Making the match more irresistible, the odds were “pick-‘em.”

The fight went the full 12 and Lewis would be credited with out-landing Evander in every round. There was a great snit when the bout was ruled a draw. The brunt of the vitriol was directed at IBF arbiter Eugenia Williams who had Holyfield winning seven rounds. She was accused of being a puppet of Holyfield’s promoter Don King.

The do-over at the Thomas and Mack was an immense attraction. The fight broke the existing Nevada record for gate receipts and the existing record for pay-per-view buys.

Holyfield did better in the rematch than in the first fight, not that one would have gleaned that from a glance at the scorecards: 117-111, 116-112, and 115-113, all for Lennox Lewis. If this had been the first fight between them instead of the second, and if this bout had been scored a draw, hardly anyone would have complained. Regardless, an injustice was rectified.

Holyfield’s next three fights were against John Ruiz, the first two in Las Vegas. Evander went 1-1-1 against Ruiz who fought out of Chelsea, Massachusetts, but yet their trilogy wasn’t a big story outside New England. Ruiz had a bland personality, manifested in his nickname, “The Quiet Man,” and an awkward style that made for dull fights.

Constantly boring ahead, Ruiz did a good job smothering Holyfield’s punches and exhibited just enough offense to warrant the decision in the minds of many people. But the judges favored Holyfield, two of whom gave him the nod by a single point.

The bout was contested at the Paris Hotel. At stake was the vacant WBA title that Lennox Lewis had forfeited. With the victory, Evander became the first four-time heavyweight champion, not that the fourth title was considered a significant achievement in the alphabet-fractured environment. The prevailing sentiment, articulated by Kevin Iole, was that Holyfield would have carved Ruiz to pieces if the bout had been held five years earlier.

Holyfield conceded that his showing wasn’t up to his standards. He blamed it on a broken eardrum which he said affected his balance and his timing. When the WBA ordered a rematch, Evander was all for it.

Typical of all great champions (with Joe Louis the classic example), Holyfield tended to perform at his best in rematches. But not this time. Despite severe swelling over both eyes and a bloody nose, Ruiz pulled away in the late rounds. He knocked Holyfield down in the 11th with a right to the temple and Holyfield, who had difficulty putting his punches together, barely survived the round. Many in the crowd left before the scorecards were read; the verdict was a foregone conclusion.

Holyfield was two weeks shy of his 41st birthday when he locked horns with James Toney on Oct. 4, 2003 at Mandalay Bay.

The 35-year-old Toney, who brought a 66-4-2 record, had won the IBF 190-pound title in his most recent outing, a fierce fight with Vassiliy Jirov. He came in at 217 for Evander, 60 pounds more than he carried when he upset Michael Nunn back in 1991. But Toney was a handful at any weight and he gave Evander the worst beating of his career. The bout was stopped midway through the ninth frame when Holyfield’s trainer Don Turner entered the ring on a mission of mercy.

Evander Holyfield’s last fight in Las Vegas came six-and-half years after his defeat by James Toney and it almost didn’t happen. The Nevada commission debated long and hard before approving his match with 41-year-old Frans Botha, the so-called “White Buffalo.”

The fight was up for grabs after seven rounds with Holyfield trailing on two of the cards. In the eighth, Evander broke through, decking Botha with a big right hand and following up with a barrage of punches after Botha made it to his feet, leading the referee to call it off. It was a messy fight with a lot of clinching and a comical moment when Botha hit both of Evander’s ears simultaneously, a maneuver, said ringside reporter Steve Carp, that the “White Buffalo” borrowed from The Three Stooges playbook.

The fight was at the Thomas and Mack. In his previous fight in this building, Holyfield fought Lennox Lewis before an animated crowd of 17,916 swelled by a large delegation of singing and chanting British fight fans. His purse was $15 million guaranteed but he stood to make even more based on the pay-per-view numbers. His fight with Frans Botha played out before a subdued crowd announced at 3,127. Evander, who was coming off back-to-back losses, reportedly fought for a purse of $150,000.

To his credit, Evander ended his 17-fight Las Vegas run on a winning note. He would fight twice more before calling it quits, leaving the sport with a 44-10-2 record.

—

The word most often used to describe Evander Holyfield is the word warrior, a word that invariably comes prefaced by the verb “great” or a synonym of it.

Former Review-Journal sports editor Jim Fossum authored a nice tribute: “Holyfield displayed heart and conditioning virtually unparalleled in boxing…(He) securely established his place in every boxing book they will print from here to eternity.”

Fossum wrote those words in April of 1994, long before Evander’s two fights with Mike Tyson and 17 years before Holyfield’s final fight!

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision