Featured Articles

Nothing Lasts Forever, Not Even Manny Pacquiao’s Exquisite Ring Career

Nothing Lasts Forever, Not Even Manny Pacquiao’s Exquisite Ring Career

If there is one thing I’ve learned as a temporary passer-through during the millions and millions of years of mankind’s Earthly existence, it is that nothing really lasts forever. Something might stay relatively the same for years, maybe even decades, but if enough time goes by it either gets better, worse or vanishes altogether.

And while that is true for all of us, the span of athletic excellence would seem to be especially abbreviated. Oliver Wendell Holmes was mentally facile enough to have served as a Justice on the United States Supreme Court until his retirement, at 90, in 1932. Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg served until she was 87, when she finally was outpointed by the Grim Reaper. Physical prowess, however, almost always has a much-earlier expiration date. If that was not apparent before, it should have been after 58-year-old, four-time former heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield didn’t make it through a single round of his recent sanctioned fight in Florida against former UFC star Vitor Belfort, 44, which never should have been allowed even as a grin-and-giggle exhibition.

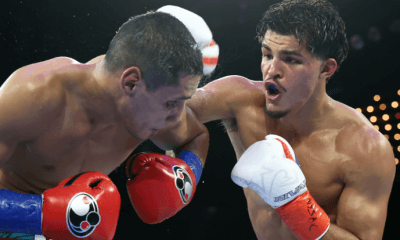

The inevitable law of diminishing returns, at least as it pertains to boxing, was reaffirmed on Wednesday when Manny Pacquiao, increasingly a graybeard of boxing at 42 but relatively youthful as a politician, announced his retirement from the ring after 26 years, 72 professional bouts, world championships in a record eight separate weight classes and, for his global legion of fans and admirers, countless memories made. Perhaps Pacquiao was influenced by his most recent and likely final bout, a 12-round, unanimous-decision loss on Aug. 21 to Yordenis Ugas, who came away with “PacMan’s” WBA welterweight title. Then again, perhaps not. A sitting member of the Philippine Senate since 2016 and prior to that a Representative of the Sarangani Province to the Philippine Congress from 2010 to 2016, it has long been his desire to someday ascend to his country’s highest elected office. If he is truly done with boxing, he can now fully focus on his bid to succeed 76-year-old incumbent Rodrigo Duterte, whose six-year term expires in 2022.

In a Facebook post confirming what many had already expected, Pacquiao said, “It is difficult for me to accept that my time as a boxer is over. Today, I am announcing my retirement. I never thought that this day would come. As I hang up my boxing gloves, I would like to thank the whole world, especially the Filipino people, for supporting Manny Pacquiao.”

Still, you have to wonder which way Pacquiao might have turned had he reached back into his glorious past to summon enough of what had made him a living legend and defeat the very capable Ugas, thus again demonstrating that he is somehow immune to the ravages of age that make even the best of the best seem merely mortal. Would his retirement announcement, previously hinted at, again be put on hold? Even given his vast popularity, could he have reasonably asked Filipino voters to go to the polls next year and cast their ballots for a part-time fighter, part-time President?

Pacquiao as the possible leader of a nation of 90 million, or even as a fighter who would go on to achieve some of all that he eventually did, seemed unlikely at best and ridiculous at worst when he made his United States debut on June 23, 2001, at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand, as a challenger to IBF super bantamweight champ Lehlo Ledwaba of South Africa in early-undercard support of the main event that paired Oscar De La Hoya with WBC super welterweight titlist Javier Castillejo. The arena and press section were both less than half-full when Pacquiao, virtually anonymous in America despite the world flyweight and junior bantamweight belts he had won while fighting almost exclusively in his homeland (only two of his previous 34 pro bouts were outside the Phillippines), stepped inside the ropes to painfully introduce himself to Ledwaba and, in a sense, everyone else who cared to take notice.

At least one U.S. writer fortunate enough to have taken his ringside seat early – me – was mesmerized by what he had seen of the little southpaw whirling dervish, who stopped Ledwaba in six one-sided rounds. I made a mental note to keep tabs on a fighter I was convinced could become something special, and as time went by Pacquiao’s emergence as a force of nature was not unlike that of a gigantic avalanche rolling down the side of a snowy mountain.

In comparing notes with longtime Associated Press boxing writer Ed Schuyler Jr., we discovered that his first glimpse of a young Panamanian destroyer named Roberto Duran, a one-round demolition of solid journeyman Benny Huertas in Madison Square Garden on Sept. 13, 1971, was as indelible as mine was of the scrawny, 22-year-old Pacquiao. Later, for a story for this site that was posted on Dec. 5, 2012, I compared my initial impression of Pacquiao to how Michael Corleone, hiding out in Sicily, felt upon seeing the lovely Apollonia in the 1972 Academy Award-winning film The Godfather, which one of Michael’s bodyguards compared to “getting hit by the thunderbolt.”

For boxing buffs, the thunderbolt strikes whenever they first-catch sight of someone they hadn’t seen before, and maybe even hadn’t heard about, but whose style, charisma or power have the effect that Apollonia had on Michael Corleone. We immediately reserve a part of our heart for that fighter, and the likelihood is that he resides there for the remainder of his ring career, and possibly forever. For diehard loyalists, the thunderbolt came in the form of a mobile, fast-handed and mouthy heavyweight named Cassius Clay, for others it was a snarling, compact wrecking machine, Mike Tyson.

Objectivity is the name of the game for professional chroniclers of the sport, and emotional and/or personal feelings shouldn’t come into play when reporting on a particular fight or fighter. There are other practitioners of the pugilistic arts I have liked as much personally, or admired as much professionally, as I have Pacquiao. Other fighters stir less-positive feelings because, well, media members are as human as anyone else. But we are obliged to call ’em as we see ’em; it is a narrow path that does not allow for much if any deviation.

There have been occasions involving other sports when the thunderbolt has struck me. As a young sports columnist for the Jackson (Miss.) Daily News, I experienced a Pacquiao-like epiphany when a sophomore running back for Jackson State, Walter Payton, revealed himself as a generational talent. Same thing when Pete Maravich showed up at LSU as a gangly freshman wunderkind who could do things with a basketball nobody had ever seen before, or when then-rookies Albert Pujols and Ken Griffey Jr. swung their bats as if they were future tickets to enshrinement in Cooperstown branded into the wood. True greatness sometimes is delayed in its arrival, but when it arrives it is impossible to look away. So, we look, and look, and keep doing so until the Paytons, Maraviches and Pacquiaos no longer can or wish to try squeezing more magic out of their expiring primes.

Is Manny Pacquiao the greatest fighter ever? Maybe not, but the roll call of those who merit a higher place in history’s pecking order is short and distinguished. The Fab Filipino didn’t linger as long as Bernard Hopkins, who was still a world-rated light heavyweight as he entered his 50s, or Archie Moore or George Foreman, but he is the only man ever to hold world titles in eight separate weight classifications or in four decades (the 1990s, 2000s, 2010s and 2020s). His 62-8-2 career record, with 39 knockouts, includes victories over a Who’s Who of boxing’s elite: Erik Morales, Marco Antonio Barrera, Oscar De La Hoya, Ricky Hatton, Miguel Cotto, Antonio Margarito, Juan Manuel Marquez, Tim Bradley, Adrien Broner and Keith Thurman.

Additional testimonials to Pacquiao shouldn’t be necessary now that he seemingly has fought his last fight, but consider these culled from insiders I have spoken to during the Age of Manny.

Prior to his Nov. 14, 2009, clash with another future Hall of Famer, Miguel Cotto (Pacquiao won on a 12th-round stoppage to claim the seventh of his eight titles in different weight classes), “PacMan’s” longtime trainer Freddie Roach offered that “Manny is a throwback. He is like Henry Armstrong (the only fighter to simultaneously hold three world titles in different weight divisions). But the amazing thing is that he’s carrying his power with him along with his speed. He is passing people like Sugar Ray Leonard and Tommy Hearns, who were six-division world champs.”

And this, from the late and great Philadelphia trainer, Naazim Richardson: “The last fighter I saw who fought like Pacquiao was Aaron Pryor. Pryor was an all-action fighter. His energy level was just extraordinary. Pacquiao brings the same level of energy into the ring. He’s so consistent. He’s fought bigger guys, but his fights have gotten easier because the high-energy guys are usually in the lower weight classes. When he’s fought bigger guys, he’s actually had an easier time.”

Enjoy your retirement from boxing, Manny, although you might find that possibly assuming the duties of your country’s presidency might make duking it out with another king of the ring seem like child’s play. Years ago you marveled at what you had accomplished inside the ropes, saying it was “more than my dreams. But then everything in my life has been so much more than my dreams.”

How many fighters – anyone, really – can say that?

Editor’s Note: Bernard Fernandez, named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Observer category with the class of 2020, was the recipient of numerous awards for writing excellence during his 28-year career as a sportswriter for the Philadelphia Daily News. Fernandez’s first book, “Championship Rounds,” a compendium of previously published material, was released in May of last year. The sequel, “Championship Rounds, Vol. 2,” with a foreword by Jim Lampley, arrives this fall. The book can be ordered through Amazon.com, in hard or soft cover, and other book-selling websites and outlets.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision