Featured Articles

Percy Pugh, Gone at 81, Deserved More Acclaim in His New Orleans Hometown

Maybe former welterweight contender Percy Pugh would have gotten his chance to deliver the acceptance speech he had rehearsed who knows how many times in his mind had he had a better campaign manager than me making his case for induction into the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame.

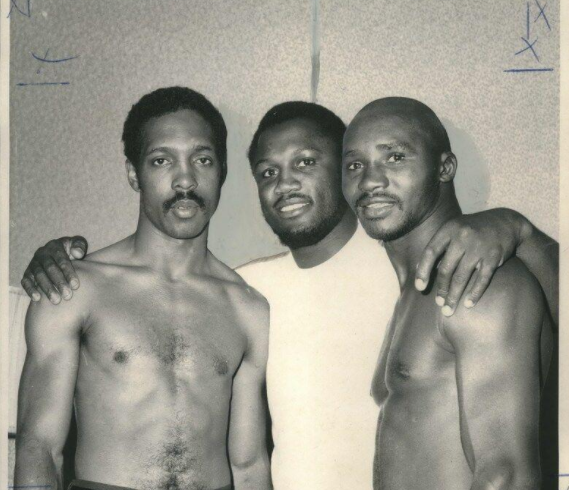

Maybe Pugh (pictured on the right with Joe Frazier and opponent Adrian Davis) would have gotten the call to his hometown’s hall had he been a much-harder-hitting puncher instead of a pugilistic Fred Astaire, winning only five of his 47 professional victories by knockout.

Maybe he would have become more of an enduring local hero had he fought for and won the world championship he was denied for years because the powers-that-be who could have made it happen treated him as if he was the spreader of a communicable disease.

And maybe he’d now have a plaque hanging in the Caesars Superdome had more members of the GNOSHOF selection committee actually seen him fight during his 1960s prime, or did enough research to realize that his not terribly impressive 47-30 career record and low KO percentage did not come close to telling the entire story of someone whose bouts regularly sold-out Municipal Auditorium and whose skill set, even without a power component, dazzled audiences around the country.

That’s a slew of maybes, and even if at some future point the electorate that has rejected his candidacy on an annual basis does an about-face and inducts him posthumously, it will be a hollow victory for his diminishing number of contemporaries who still cling to the hope that he eventually will get his due. Percy’s friends and relatives are aging fast or already gone, and the reality of any Hall of Fame is that all potential inductees would much prefer to enjoy the moment while they’re still breathing and on this side of the grass.

In a story authored by John Reid that appeared in the July 13, 2000, issues of The Times-Picayune, the headline read that Percy Pugh, who once was boxing’s No. 1-ranked welterweight, was “…one of the best boxers the world never saw.”

There is so much going on in today’s world, what with the pandemic that is now in its third year, skyrocketing inflation, political turmoil and international intrigue, that the death of an 81-year-old fighter whose ring career as an active participant ended on May 18, 1974, with the last of 10 consecutive defeats, does not rate much, if any, attention. But maybe it shouldn’t be totally overlooked, either.

As a native New Orleanian who saw Percy Pugh fight live and in person on several occasions, making for some indelible memories, I felt compelled to make his case for induction into the GNOSHOF, as I had successfully done for three other athletes who I thought merited such recognition (a basketball player, tennis player and football player). It wasn’t as if I thought Percy deserved inclusion in the International Boxing Hall of Fame; I acknowledge his career had little to no chance of clearing the extremely high bar for admission to that exclusive club in Canastota, N.Y. But in New Orleans, which once had been a hotbed of boxing, his prime years as a popular and accomplished main-event attraction seemed to me worthy of serious consideration.

The boxing contingent in the GNOSHOF includes former world champions Pete Herman (inducted in 1971), Willie Pastrano (1973), Joe Brown (1977), Ralph Dupas (1978) and Tony Canzoneri (1984), as well as non-champions Bernard Docusen (1976), Marty Burke (1978) and Jimmy Perrin (1979). Dr. Eddie Flynn (1981) was never a pro, but he was honored for being an NCAA boxing champion as well as a member of the 1932 U.S. Olympic boxing team. Other inductees affiliated with boxing include trainer Whitey Esneault (2006), referee Elmo Adolph (2000) and promoter/manager Les Bonano (2021).

Where Philadelphia is renowned for its assembly line of left-hooking knockout artists, New Orleans was better known as the birthing place of slick boxers with fancy footwork, active jabs and negligible pop. That subset includes Herman, Dupas, Pastrano (some of whose moves were copied by the young Cassius Clay) and, for a heady time in the ’60s, Pugh.

Les Bonano, whose half-century in boxing was rewarded with his 2021 induction into the GNOSHOF, recalled happy times when he was involved with Pugh in various capacities. “Percy and I traveled the world together,” Bonano told writer Ted Lewis for the obituary of Pugh that appeared in the The New Orleans Advocate/Times-Picayune. “And everywhere we went, we ran into people who knew Percy. He loved to make people laugh when he was in the ring, and he loved to tell boxing stories. How could you not love a guy like that?”

But time passes and memories fade, and by and by those who appreciated Pugh as a stick-and-move escape artist who could make opponents look foolish either took their own eternal 10-count or moved on to other objects of fascination.

Two-time former heavyweight champion Chris Byrd once explained why his mobile, quick-hitting style, which might be described as a larger, left-handed version of Pugh’s, so infuriated opponents. “Nobody likes getting clowned,” he said, “clowning” being the ability to frustrate even good opponents who’d prefer that the other guy stay put and linger in the hitting zone.

“Tat-tat-tat, that’s how fast I was,” Pugh said in the 2000 story written by Reid. “I could bounce, move and stick my punches. A lot of people didn’t see them coming.”

Possibly one of the people who didn’t want to get hit with something he didn’t see, or miss with something he was trying to hit himself, was welterweight champion Curtis Cokes. Although Cokes dropped more than a few hints that he would eventually get around to sharing a ring with Pugh, the fight never happened. Nor would it, once Pugh suffered a couple of close losses that dropped him from his No. 1 ranking.

“I know I should have gotten my shot,” Pugh, still displeased decades after being passed over, recalled in 2000. “Everybody knows it.”

Minus the title bout he never got to appear in, the career high points for Pugh were his two showdowns with Jerry Pellegrini, a fellow main-eventer in New Orleans who was everything Pugh wasn’t: white, a big puncher and not nearly as fleet-footed and fast-handed. Pugh won both bouts by unanimous decision, the first a 10-rounder and the second a 15-rounder in which he annexed Pellegrini’s Southern 147-pound title. Each fight drew a sellout crowd of 5,000-plus in Municipal Auditorium, with segregated seating.

“The first fight should have been called a draw, but the second one he outscored me over 15 rounds,” Pellegrini recalled. “Percy was a good fighter. He was No. 1 in the world.

“But you know, Percy had white supporters and I had black supporters. I think people rooted for me because I got a lot of knockouts and they rooted for Percy because of the way he could move. But we both filled up the auditorium.”

One of my most lasting memories of Percy Pugh came on Feb. 24, 1989. I was in Las Vegas to cover Mike Tyson’s first of two fights with England’s Frank Bruno which would take place the following night at the Las Vegas Hilton. A large tent with a big-screen TV had been set up in the hotel’s parking lot so media members could watch the fight in snowy Atlantic City in which Roberto Duran again defied Father Time to dethrone WBC middleweight champion Iran Barkley by split decision.

I was talking outside the tent with Les Bonano, whom I had known for many years, when Percy Pugh, who was training one of Bonano’s fighters who would appear on the Tyson-Bruno undercard, dropped by. “Percy, I want to introduce you to Bernard Fernandez, the boxing writer for the Philadelphia Daily News,” Les said. I stuck out my hand to shake Percy’s, which he did with a limp grip and no enthusiasm for having just made my acquaintance.

“But you don’t understand,” Les told him. “Bernard is from New Orleans. He saw you fight several times.”

“Including both times you beat Jerry Pellegrini in Municipal Auditorium,” I told Percy, who perked up immediately. We spent the next 15 minutes discussing those fights (full disclosure: Jerry Pellegrini is a friend of mine) at some length, and I could sense that his being remembered, maybe particularly for those two fights, had the effect of making him feel that his past had not completely faded away, that there were still people who appreciated who and what he had been when he was at his best.

I can only speculate as to how fulfilling it would have been for Percy Pugh to have been accorded the recognition from the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame that Les Bonano and I believed then, and still do, he deserved.

Image: 1970 NOLA file photo

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision