Featured Articles

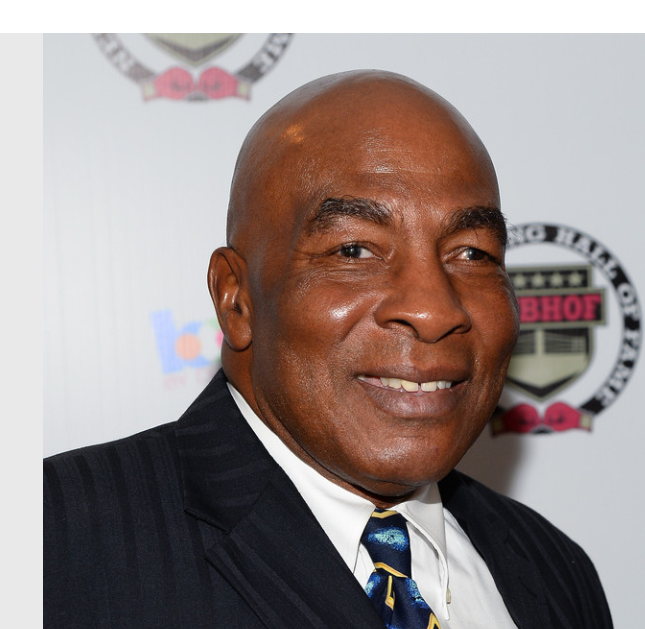

Earnie Shavers, Gone at 78, Was The Bambino of Boxing’s Biggest Boppers

Earnie Shavers, Gone at 78, Was The Bambino of Boxing’s Biggest Boppers

The technology of sports today, most of them anyway, has become so advanced that what once was the stuff of legend – tales of incredible individual feats that tended to grow taller with the passage of time – now seem like mathematical equations more appropriate for a NASA space launch. Take baseball, for example. The exact distance of every home run hit now in the big leagues almost instantly can be determined by a computer, which also supplies such minutiae as the ball’s exit velocity and the launch angle of the batter’s swing.

All of which means that no matter how many home runs New York Yankees slugger Aaron Judge crushes this season, or how precisely calculated the distances of some of his longer blasts are, he can never fire a modern fan’s imagination to the extent that a pre-computerized Babe Ruth did. One of the most oft-recited examples of Ruthian prowess is the ball he hit for his 714th and final homer, and third of the day, when the 40-year-old Babe, then playing for the Boston Braves, completely cleared the 86-foot stands of Pittsburgh’s spacious Forbes Field. The ball landed on the roof of a rowhouse across the street, some eyewitnesses swearing that it even flew over the roof by 50 feet. The generally accepted distance for Ruth’s career parting shot is an epic 600 feet, which fans are free to believe or not.

Boxing’s analytics have not yet caught up to baseball’s, although CompuBox’s punch-counting statistics at least give the sweet science a veneer of what might yet be. Don’t dismiss the possibility that someday in the not-too-distant future computer chips will be embedded in fighter’s gloves that will provide detailed information as to how many pounds per square inch were delivered by a knockout blow. When and if that day comes, much of the wonderment attached to fans’ fascination with power punchers will be reduced to cold, hard and mostly dissatisfying statistics.

It would be overstating matters to describe heavyweight slugger Earnie Shavers, who passed away Thursday, the day after his 78th birthday, as “The Bambino” of boxing. Unlike Ruth, still arguably the greatest baseball player of all time and whose 714th home-run ball is still a cherished memento in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., Shavers is not an inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, and likely never will be. He has certain losses to at least partially offset his raft of awe-inspiring knockout victories, and historians can argue, correctly, that “The Acorn” – the nickname conferred upon him by Muhammad Ali – had stamina issues that limited his maximum effectiveness to five or six rounds, as well as a relative inability to shake off the kind of big punches that he so routinely delivered.

The power quotient of the 6’1”, 210-pound Shavers, however, has continued to be discussed in the manner of those who somehow have been at ground zero during a tornado or a tsunami. Even those who survived the potential natural disaster of having shared the ring with him speak of the experience with hushed reverence.

“Man, I been in there with the best,” said James “Quick” Tillis, who scored a 10-round unanimous decision over Shavers on June 10, 1982. “I fought a bald-headed guy named Earnie Shavers, who was the baddest dude in the world. He hit so hard, he could turn goat milk into gasoline.”

And this, from Randall “Tex” Cobb, who stopped Shavers in eight rounds on Aug. 2, 1980: “Nobody hits like Shavers. If anybody hit harder than Shavers, I’d shoot him.”

Also this, from Ron Lyle, after he scored a six-round TKO over Shavers on Sept. 13, 1975: “Hey, man, that’s the hardest I’ve ever been hit in my life. George Foreman could punch, but none of them could like hit Earnie Shavers did. When he hit you, the lights went out. I can laugh about it now, but at the time it wasn’t funny.”

A 35-year-old Ali was pushed to the limit in defending his WBA, WBC and The Ring heavyweight titles on a 15-round unanimous decision on Sept. 29, 1977, after which he remarked that “Earnie hit me so hard, it shook my kinfolk in Africa.” He further noted that Shavers was “stronger than Joe Frazier and George Foreman. I don’t know why I picked on him so late in my career.”

The Ali bout was the first of Shavers’ two bids for his sport’s grandest prize, but it wasn’t his most notable career near-achievement. That would be his rematch with WBC champion Larry Holmes on Sept. 28, 1979, at Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace. They previously had fought on March 25, 1978, with Holmes, who had yet to win the title, winning a 12-round unanimous decision.

Holmes had plunged to the canvas in the seventh round as if poleaxed by the kind of percussive shot that almost without fail resulted into Shavers winning right then and there. But this was the “Easton Assassin,” whose recuperative powers on this night would prove a match for the challenger’s vaunted firepower.

“If I had one fight, one moment, I could do over, it’d be in the second fight with Larry Holmes,” a reflective Shavers recalled years later. “The punch I had been trying to land all night finally found its mark. An overhand right caught Holmes flush on the button, and down as if he had been deboned. As I headed to the neutral corner, Holmes didn’t stir. I was the heavyweight champion of the world. All my troubles were finally over. It was the greatest feeling I’d ever had. And it lasted for five whole seconds.”

Holmes, who surprised maybe even himself by pulling himself back onto his feet before the count reached 10, somehow made it to the bell ending the round and thereafter seized control again en route to winning by 11th-round TKO. But he never forgot what it was like to be drilled like he’d never been nailed before or later. He would later say that Shavers had hit him harder than Mike Tyson did.

“Man, I still got knots in my head where he hit me,” the “Easton Assassin” recalled. “Earnie could punch very hard, incredibly hard. I hear people say, `Aw, man, he couldn’t possibly have hit as hard as everyone says.’ They think the stories about Earnie’s power are exaggerated. It’s no exaggeration. That power was real.”

Perhaps, had he not risen to prominence in the midst of one of the most gilded golden ages of heavyweight boxing in the 1970s and into the early ’80s, Shavers might have claimed an alphabet title during a less talent-rich era. But being very good, and exceptionally on those occasions when he got there first with a massive shot, wasn’t good enough considering that Shavers’ contemporaries included Ali, Holmes, Foreman, Frazier, Lyle, Gerry Cooney, Ken Norton, Michael Spinks, Jerry Quarry, Jimmy Ellis, George Chuvalo, Jimmy Ellis and Oscar Bonavena. And while Shavers registered quick knockouts of Norton, Ellis and Young, he also lost inside the distance in matchups with Lyle, Cobb, Quarry and Bernardo Mercado. Including two ill-advised comebacks in 1987 and ’95, he finished 74-14-1, with 68 KOs.

I interviewed Shavers for a fight card on Sept. 26, 2013, at the Sands Bethlehem Events Center in Bethlehem, Pa. He was there along with fellow golden oldies Holmes, Cooney and Thomas Hearns for a meet-and-greet with fans that had paid an additional fee to get autographs and to pose for pictures.

Asked whom he considered to be the hardest-hitting heavyweight, Shavers, then 68, not surprisingly, described himself as “Number One. No one can outpunch me, except God.”

Any list, be it pound-for-pound, hardest puncher, best boxer or whatever, is subjective. Opinions will always vary. In 2003, Shavers was listed as the 10th-greatest puncher of all time, regardless of weight class, by The Ring, following heavyweights Joe Louis (1), Jack Dempsey (7) and Foreman (9), but ahead of Rocky Marciano (14), Sonny Liston (15) and Tyson (16). Another list of the “Hardest hitters in heavyweight history,” was posted by ESPN.com’s Graham Houston on Dec. 27, 2007, and it had Tyson at No. 1, Louis third, Foreman fourth, Marciano fifth and Shavers sixth.

A more recent such list, The Ring’s 100 greatest punchers of the last 100 years, appeared in a special June 2022 collector’s special. Louis again got the top spot, with Dempsey (4), Foreman (5) and Shavers (6) also in the top 10. The second 10 included heavyweights Marciano (11), Liston (12), Tyson (13), Deontay Wilder (16) and Max Baer (20).

Lists spark debates, and arguing the merits of fighters from different eras has always been a component of what makes boxing enthralling. Was Shavers the biggest hitter ever? Maybe, or maybe not. But he deserves to be in any such discussion, and that should be good enough. God forbid that the barroom arguments that have always sufficed until now move into the realm of digital printouts.

Somewhere, the late, great Babe Ruth probably is glad that he played his game the way it was then.

Bernard Fernandez, named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Observer category with the Class of 2020, was the recipient of numerous awards for writing excellence during his 28-year career as a sports writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. Fernandez’s first book, “Championship Rounds,” a compendium of previously published material, was released in May of last year. The sequel, “Championship Rounds, Round 2,” with a foreword by Jim Lampley, is currently out. The anthology can be ordered through Amazon.com and other book-selling websites and outlets.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision