Featured Articles

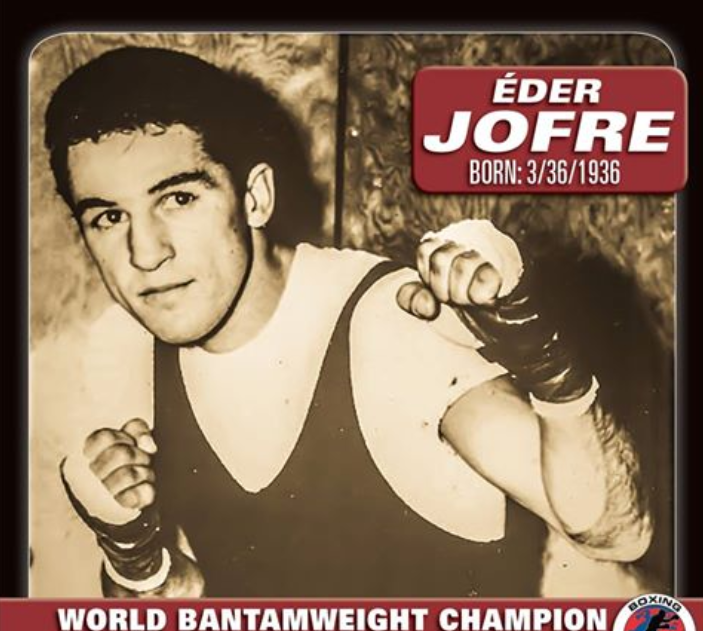

Rest In Peace Eder Jofre

“I just thrill at that boy’s performance. He is a marvel of boxing perfection. There is nothing he cannot do.” – Barney Ross.

Between 1957 when he turned professional and 1965 when Fighting Harada caught up with him, Eder Jofre was 46-0-3. He reached heights that so few fighters have reached that you could probably name them without straining. He passed away this morning in Sau Paulo, Brazil, from pneumonia aged eighty-six. He had been hospitalised since March.

To say that his was a life well lived is an understatement.

Jofre was born in Sau Paulo in 1936, a decade that reflected this one in that it was a time of great political upheaval in his beloved Brazil, the thirties seeing the end of the Brazilian Republic, a communist uprising, a fascist uprising, and iterations of new constitutions peeled off like playing cards. It seemed to be sport, not politics that drove Jofre’s people though and his father had tried a fair hand at amateur boxing, later joining his brother to become a coach. The stars aligned and a fistic immortal rose from Brazil’s political ruins.

“At a young age,” wrote Chris Smith, author of the definitive Jofre biography Brazil’s First Boxing Champion, “[his father] put the gloves on Eder and started teaching him techniques and punching patterns…it wasn’t long before little Eder was jumping rope with the professionals.”

By the time he was seven years old, he was training like an amateur boxer and soberly asking his father’s permission to thrash school bullies. By the age of sixteen he was fighting as an amateur and in 1956 he was a part of the Brazilian Olympic team that travelled to Melbourne, Australia where he was eliminated before the medals by Chilean Claudio Barrientos – who would be stopped in eight rounds by Jofre when they met up again in the professional ranks.

Those professional ranks beckoned him a few months after his Olympic failure, the same time at which he decided to become a vegetarian, something he remained committed to until his death. Early results were good. While Jofre was troubled by a tiny handful of South American draws, a local phenomenon that called for a wider separation of the fighters that was generally called for in the rest of the world, “O Galo De Ouro” as he would soon come to be known had set upon the road that would culminate in one of the finest runs in bantamweight and boxing history.

Another foible of the South American boxing landscape of the 1950s and 1960s was that in the unlikely event that you were able to free yourself from the massed banditry of the local toughs, you would often have to meet with ranked opposition before you were even allowed to contest for regional titles. Imagine the horror this notion would inflict upon the rather spoiled fighters of today, fighters who often achieve world championships without having to meet with the best.

For his part, Jofre ran up against the Filipino Leo Espinosa in June of 1959. Espinosa, a former flyweight, had extended the immortal Pascual Perez the full fifteen in 1956, even picking up a few rounds, before conquering a man who would soon be a fine champion in his own right, Pone Kingpetch, in 1957. He had a pedigree in excess of Jofre who had boxed just twenty-five contests. Jofre admitted to his father before this fight that he was afraid, and his father suggested they cancel.

“No. That’s the way it is. Afraid or not, I am fighting.”

Such was his life.

It was not just Jofre’s career which was in its infancy but also the boxing in Brazil – Espinosa seems to have been only the second world-class fighter to visit the country and so as Eder went, so did boxing in Brazil. Jofre did not let his countrymen down. In the fifth he dropped the visiting Filipino with a gorgeous left hook – there is a famous photograph of Jofre bouncing, looking away from his fallen foe, his feet not touching the ground, frozen with both feet an inch above the canvas, floating. Espinosa got his disorganised legs under him and although he remained cool as Jofre’s battle-fever and inexperience showed, there was little likelihood of his winning after suffering such a blow. Jofre had graduated in a ten-round decision.

This set him loose on the trail of the South American Bantamweight title, a far more worthy, storied championship than it is today and held by the world-ranked Argentine Ernesto Miranda. For those who are not aware, Argentina-Brazil is as great a sporting rivalry as exists and his series with Miranda was the key rivalry of the first half of Jofre’s career. The two had met twice in 1957, registering a pair of draws before their respective careers diverged, and now they were to settle matters for the title. Their third fight, in February of 1960, was a strange affair in which Eder fought aggressively but was made to miss by Miranda, who never looked like winning but who boxed carefully enough to undermine Jofre’s offence.

This lack of aggression makes Miranda’s behaviour prior to their fourth encounter a few months later even stranger. Miranda behaved like a man fueled by hate, even stooping so low as to send insulting letters to Jofre’s wife and family. One must be wary of projecting on to great historical figures in unpicking their motives but here it seems to me is a key moment for Jofre. His bad intentions seem to me to have been unlocked by Miranda, not just in the fourth and final fight of their rivalry but for all time. Not even world-class opposition would be safe after this night.

It was not that Jofre was more aggressive than in their third fight, but rather he seems to have been more controlled. He missed less, countered more and made a backfoot fight impossible for Miranda. They waged war with not a moment’s doubt as to the outcome. It was Jofre in three. After destroying his rival in the ring, Jofre the man found it within himself to forgive Miranda for some obscene pre-fight behaviour and even take him into his confidences.

It was inevitable now that Jofre would receive a shot at the title although for the privilege, Jofre had to travel to Los Angeles where he dominated and stopped the overmatched Eloy Sanchez in November of 1960. A brief and disturbing brush with the Italian Mafia aside, the championship fight went off without a hitch. Jofre cheerly named the bantamweight title a wedding gift for his wife-to-be.

In 1961 Jofre was matched with the world-class Italian Piero Rollo. Rollo had been beaten before, but never stopped by punches – so brutally did Jofre handle him that he was unable to answer the bell for the tenth. It was a sensational display of total dominance.

“I am never in a hurry,” Jofre explained, that control again.

“He is the best bantam in the world,” offered a barely recognisable Rollo.

I submit that Jofre was by this point already technically complete. When he met Johnny Caldwell the following year – Caldwell, too, made the awful mistake of making his contest with Jofre personal – he was as beautifully balanced as it is possible for a fighter to be, almost never out of punching position, delivering on boxing’s manual on shot after shot while also riffing on the classics. His uppercut, especially, was a thing of genuine beauty; Jofre could make space for that punch almost anywhere and throw it from unusual ranges and angles, making of it then a feint that certainly tied Caldwell in knots. An unbeaten Northern Irishman, it is hard to exaggerate just how tough this man was, but Jofre beat him so badly as to see him rescued by his distressed manager in the tenth.

The title picture, which had become confused by the retirement of Jose Becerra, was now clear – it was Jofre. Indisputably the world’s number one bantamweight, he would remain so for the first half of the 1960s, dismissing Herman Marquez, Kat Aoki, and, against the man most likely to rule if Jofre had never been born, he repeated his 1960 knockout of Jose Medel, this time in just six rounds. In 1964 he turned in his last great winning performance against Bernardo Caraballo, one of the most underrated bantamweights of all and the most underrated bantamweight of the era. Caraballo, out of Colombia, passed away himself earlier this year, and just as Jofre led the charge for boxing in Brazil, so did Caraballo in his country.

In the 1960s, in their primes, they duke it out ring-centre for control, both stylists, both big for the weight, both hungry for personal and national glory. This, I suspect, is not a fight any 118lb man could win against Jofre and soon enough Caraballo is moving away square, disorganised, harassed. He succumbed in seven.

Jofre spans the eras. When he won his titles he was boxing for the old incarnations, the NYSAC, the NBA, by the time he lost them, he was defending the WBC and WBA championships, certainty ebbed even as his greatness flowed. The wonderful Fighting Harada was the man who came for him, by then tight at the weight and giving up a clear style advantage to his Japanese foe, Jofre was still able to make the rematch razor-thin after dropping a clear decision in the first fight. More glory awaited at featherweight in something of a second career, but Jofre’s best was behind him. He finally hung them up in 1976 during Muhammad Ali’s second reign; when he turned professional, Rocky Marciano had just retired.

This is a very short version of a very great ring-career. What is not posited here is his personal life. Eder’s was rich. He was happily married to Cidinha for more than fifty years; he had a close relationship with his children, who travelled with him, not least in his twilight years when Jofre revisited the site of his title-winning fight with Eloy Sanchez. He lived a life any one of us could be proud of after boxing, working in politics and Brazilian civil service, continuing to make friends right up until the very end.

I spoke to author Chris Smith about his enduring memory of Jofre, with whom he worked closely on their recently published book.

“A year ago, I had the pleasure of hosting him and his two kids and I asked him a few times “how are you feeling champ?” And he’d always respond “very, very happy.” He told me he was the happiest person in the world.”

Beat that.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles1 day ago

Featured Articles1 day agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden