Featured Articles

Terry McGovern: The Year of the Butcher – Part Two, The Dixon of Old

Terry McGovern: The Year of the Butcher – Part Two, The Dixon of Old

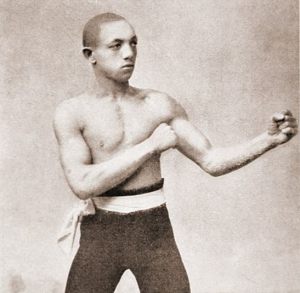

“They used to say,” wrote The Washington Times, some years after McGovern’s retirement, “that Terry started to beat his man before the first gong rang. As he sat in his corner he would glare across the ring at an adversary, his face drawn and scowling.”

This will sound familiar to boxing fans raised on stories of the intimidating qualities of Mike Tyson and before him, Sonny Liston. The ability of the biggest men to unnerve is well known but the ability of the smaller men to menace is rarely as celebrated. The main difference between McGovern and a fighter like Liston or Tyson was not that he was smaller but that he was able to dominate the men that did not fear him. Tyson was found out by deluxe journeymen James “Buster” Douglas, immunised to Tyson’s intimidation by the recent death of his mother; Liston was outmaneuvered by an ego on wheels by the name of Muhammad Ali. But when McGovern first brushed up against a fighter far too good to feel even a sliver of fear, he crushed him utterly, defeating Pedlar Palmer, the bantamweight champion of the world in a little over two minutes in September of 1899. The century ended amidst carnage and savagery as nine overmatched and terrified opponents were dispatched in a total of fifteen rounds. Even the world class Harry Forbes, who would go on to win and defend the bantamweight title, could not extend McGovern beyond two.

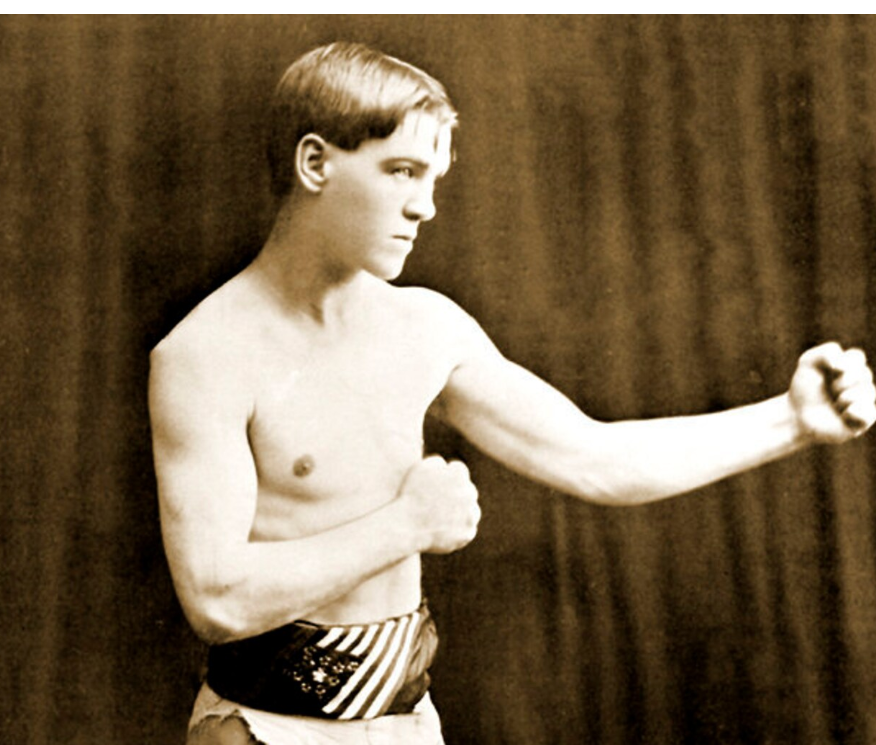

But his first opponent for 1900 was not a man who could be intimidated by a look, nor even a thirteen-fight knockout streak. His first opponent for 1900 took heed of the brutality McGovern inflicted upon Palmer and the money he made for doing it and calmly issued a challenge, which McGovern calmly accepted. His first opponent for 1900 was George Dixon, the featherweight champion of the world, arguably the greatest fighter in history up until that point. Dixon feared no man.

He had been competing in title fights across two weights for ten years, and had lost only two of those fights, dropping a narrow decision to the great Frank Erne in 1896, avenged the following year in style against an opponent who by then was weighing in as a lightweight. When he dropped another close decision to former KO victim Solly Smith in 1897 there were respectful murmurs that perhaps the genius had stepped past his best – but little surprise when he rallied to reclaim his title and make a further nine defences.

George Dixon

Those titles, those defences were a part of the Dixon story too. He was the first black man to win a world championship; he was the first Canadian to win a world championship – he was a stylistic trailblazer stiffening overmatched opponents with mobility and technique years before the supposed grandfather of modern boxing, James J Corbett, turned professional. It is reasonable to suggest that Terry McGovern was not qualified to fight him.

And yet, when money began to exchange hands, Terry McGovern was the favourite.

Partly, this was caused by sentiment. Terry McGovern was fighting Irish, the embodiment of the most beloved fighter in history at that point, former heavyweight champion John L Sullivan. Whenever McGovern’s cheerful dialogue with his beloved mother was printed in a newspaper, which in the early days were often, newspapers were sure to stress her first generation immigrant brogue in descriptive print. He was white; Dixon, though enormously respected by the white press and subject to very little of the bizarre speculations about heart or punch resistance in the body that were routinely levelled at other top black fighters, was still a black man, one who had turned professional only twenty years after the end of the American civil war. But there was more than emotion and the casual racism of the day at work – a sense was building that Dixon’s time had passed and that McGovern’s was now.

McGovern trained for a long fight, and once again he did not leave New York, where the fight was to be held, but ensconced himself in Fleetwood, a township just north of the Bronx. His dedication to re-developing his stamina was impressive given his power-punching decimation of the division at large. McGovern knew what he was faced with. It made his eerie confidence more persuasive. Some talked of an over-developed hardness to his body and possible problems making the weight limit, but such rumours had evaporated by the seventh of January, two days before the fight.

Dixon’s camp, situated in Lakewood, New Jersey, seemed equally excellent. “If appearances count for anything,” wrote the Washington Evening Star, “Dixon is the Dixon of old…he thinks well of McGovern but believes he will beat him.”

By the sixth, the odds were lengthening, but for those in attendance it was a mystery as to why. “When McGovern faces Dixon,” reported the St.Louis Republic, “he will meet the greatest fighter ever at the weight. As a ring general Dixon has no equal…[he] is a perfect fighting machine. He never misses a chance to inflict punishment.”

This is an oft-forgotten fact where Dixon is concerned. Because he was deemed by his peers the definitive “scientist” for his era, he is treated by many modern sources as a box-mover who used a famous left to keep his opponents at bay, and his famous footwork to keep himself from the furnace: for those labouring under this impression, please take note – nothing could be further from the truth. He did have that educated stiff left; he did use clever footwork to manipulate befuddled opponents; but Dixon was an aggressive, surging, war-machine, not some pit-a-pat rainy-day spoiler. Yes, at times he employed skill to close opponents down and sew decisions up, but when strategy called for it, he attacked two-handed and showed great prowess in doing so.

McGovern quit serious training two days before the fight, restricting himself mainly to running in order that he might easily make weight. “I don’t know that I ever felt better,” he cheerily informed visitors. “I expect to win a hard fight.”

Dixon hit weight six days before the fight. A reporter asked him how long he felt he could last in the ring with such a prestigious foe. “A full day,” was the answer.

The two men were first able to run the rule over one-another at the weigh in, just after two pm on the ninth of January, the day of the combat. In attendance was Barbados Joe Walcott, and roughhousing between he and Dixon’s manager Tom O’Rourke nearly ended in disaster when a kick aimed at the legendary welterweight instead connected with McGovern’s knee as much to the alarm of Dixon as O’Rourke; McGovern delightedly waved away any sense of impropriety accepting O’Rourke’s assurances of an accident as if the manager had his own best interests at heart rather than Dixon’s. The two fighters walked to the scale almost arm-in-arm; when they measured for height and when McGovern came away half an inch taller he announced “I got you whipped now!” and Dixon leaned back, hands laced, grinning. McGovern stripped naked and stepped up, Dixon after him, more modestly dressed, but both came in under the agreed 118lb limit – no official weights were taken, though Dixon reported that he weighed 116lbs that morning and expected to be 120lbs in the ring that evening; McGovern had measured a half pound heaver at first light.

“Dixon seemed to be in the better condition,” was the report that went out on the wire. “He was full of life and energy and looked as if the making of the weight had not troubled him,” whereas “McGovern seemed to be too finely drawn.”

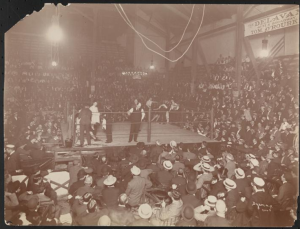

They separated cordially and just under seven hours later they were in the ring. Staged in the arena of Manhattan’s Broadway Athletic Club, it was the most significant meeting between featherweights to that date, and astonishingly, it almost inarguably remains so today. Both list among the twenty greatest fighters in all of history by my estimation; on only a handful of occasions in all of boxing have two such behemoths clashed.

Broadway Athletic Club

An American, McGovern entered the ring draped in the Irish flag, at his waist an emerald-green silk belt; the Canadian, Dixon, wore an American flag. McGovern crossed the ring and the two shook hands warmly.

Then, at around nine thirty-five in the evening, the bell for the opening round sounded and the warmth departed McGovern’s soul. He crushed Dixon like a bug.

This great champion, this man who liked to boast, if a legend so great can be said to boast, that he had visited the canvas only once in four-hundred fights, would visit it eight times in the next thirty minutes and when he left the ring he would leave the better part of his brilliance at the feet of a fighter now boxing with the apocalyptic savagery of a butcher turned trained killer.

But it was Dixon who opened more aggressively. He “waded in” according to The Brooklyn Eagle, “and was the first to lead, McGovern letting a vicious lead go over his shoulder.” Twice in the opening seconds Dixon tried his left and twice McGovern ditched them and landed body-punches over the kidneys, under the heart, and before the first minute was up, Dixon had given ground and had his back to the ropes. “McGovern crowded in,” reported The New York Tribune, “pounding his right to the ribs.” Dixon’s problem was cradled within a nutshell sealed in those precious moments; his punches, even when they landed, were not enough to deter McGovern’s furious assault upon the body.

“In years gone by,” explained the Eagle, “Dixon never hit any man but once as he hit blows in the spots that he rained upon Terry…last night it was different…his heaviest blows were to no avail against the rugged McGovern.”

Dixon was faced with the disastrous prospect of having to box and move for twenty-five rounds against a 5’4 juggernaut with darkening plans for his internal organs or grit his teeth and try to break him. He chose to try to break him.

Such was Dixon’s brilliance that the beam began to tip; a savage and fast second round was likely in McGovern’s favour, but in the third, as McGovern rattled his ribs and liver, Dixon ripped across a hook to the ear and McGovern peeled away, hurt. Two left jabs and a right hand to the jaw then “staggered Mac” according to the wire report before one-two “almost dropped Mac to the floor.”

At the bell to end the third, the betting at ringside was even for the first time since the fight’s announcement, but this was the nearest Dixon would come to a triumph; by the end of the seventh, no bets on McGovern were being taken.

It was in the fourth that he turned the tide against his prestigious foe, brutalising his body with multiple shots every time Dixon punched. In the fifth McGovern was less destructive but was now boring his way inexorably towards domination, and if Dixon took a share, it was a share of his own ashes.

He began to give way to McGovern in the seventh. His nose was erroneously reported as being broken in several newspapers, but it does appear to have exploded in a geyser of blood at the tip of a McGovern left hand, the canvas and the ropes drenched. Twice in the eighth Dixon slipped in the mess of his own blood and McGovern helped him to his feet, attacking the body, now the blood-sodden face, the body, now the head. The Evening Star describes a fighter beaten in the normal way, “his nose broken and his body covered with bruises…groping blindly in a vain but game effort to once more face his antagonists” but other reports indicate something even more fundamental was happening. Like a dog that has been drinking from a poisoned well, there is a sense of a fighter winding down towards an end. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described “a worn out fighting machine” that was “working smoothly but not strongly” against some new generation of machine too advanced to be reckoned with.

The lights in Dixon went out with the eighth as he was lashed repeatedly to the canvas by McGovern, who was completely unharmed. After the fourth or fifth knockdown, Dixon flinched, reluctant to stand with McGovern so near. “Don’t worry George,” McGovern assured him with what seemed an entirely genuine smile. “I won’t cop any sneak on you.” True to his word, McGovern permitted Dixon to stand unmolested. Then he beat the art out of the greatest fistic artist of his era. They threw in the sponge at the very end of the eighth round; Dixon never recovered.

Terry McGovern was now the bantamweight and the featherweight champion of the world. He was twenty years old.

The following month, an article appeared in the St. Paul Globe criticising McGovern’s management.

“Terry McGovern may be matched to box …Championship Lightweight Frank Erne in Chicago in the near future. McGovern may make a mistake going out of his class…A defeat at the hands Erne would do the clever little boxer a vast deal of harm. McGovern would do better to stick to his knitting.”

Franke Erne likely considered the ten-thousand dollars McGovern shared with Dixon and hoped he would suffer a rush of blood and make the match. Erne was, after all, the best fighter in the world at the 135lb limit and surely beyond even the heavy-duty machinations of McGovern, who was weighing in at flyweight just three short years before.

Well McGovern would have that rush of blood. And Erne wouldn’t last three rounds.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave