Featured Articles

‘How To Box’ by Joe Louis: Part 1 – The Foundations of Skill

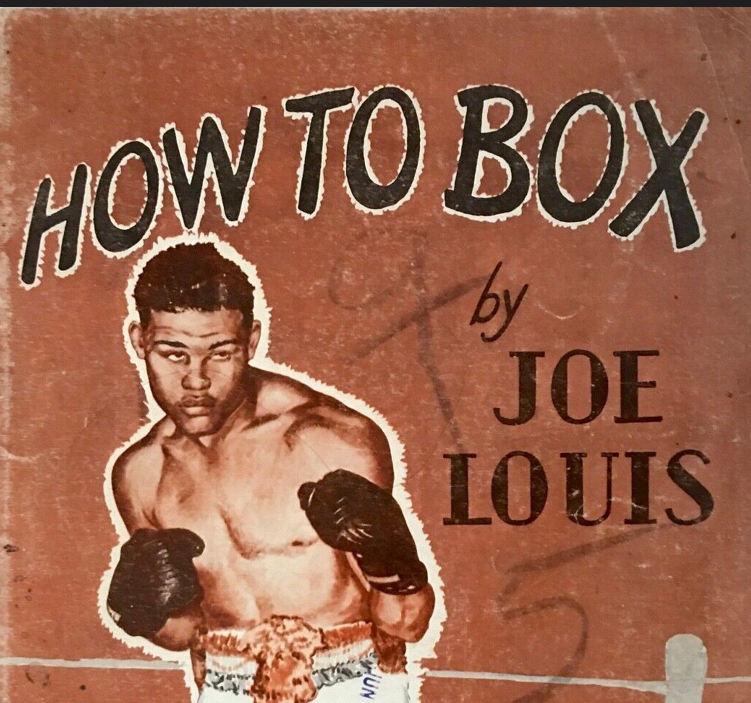

It’s still in print. You can log on to Amazon right now and buy one for yourself, renamed, repackaged, all shiny and new. But I like that mine is old. It comes straight out of Joe’s own era, has followed its own path through these past seventy years to find itself in my hands. It was printed late in 1948 in those perfect months that followed Joe’s eventual destruction of Jersey Joe Walcott in the rematch of their first controversial meeting, after his twenty-fifth straight title defence but before his ill-fated comeback. A legend, a hero, there had never been one quite like him, there arguably never would be again.

Heavily ghosted by Edward J. Mallory, How to Box was not exclusively in Joe’s own words, but it was a capture of his technical essence. Nobody, not Louis, not Mallory, certainly not I myself can take something as perfectly formed and improbable as the boxer born Joseph Louis Barrow and expect to produce a story fully told with only words. Homer himself, wonderful though his account of the boxing match between Epeus and Eurylas may have been, could not have conveyed the splendour of Joe Louis in full flow, so for me, the task is impossible.

But then, nor can I describe the feat of engineering that is The Ambassador Bridge. The nuts, though. The bolts. Hand me them one at a time and I can describe them to you. If we work at it long enough and hard enough, maybe we can begin to understand the process that brought it together, the building of the bridge that once allowed us to cross the water and visit the Joe Louis Arena in Detroit.

The nuts and bolts of Joe’s brilliant engineering are here in this book. If we could put this instruction manual to work for us and study the construction for ourselves, what might we find out? It’s an intriguing idea and one that wouldn’t leave me alone. The result is this close look at Joe Louis, based primarily upon How to Box but with conclusions drawn only from the fight films that travelled the same crooked path as the manual, all the way from the thirties and forties and into our possession. No doubt there will be blind alleys and false leads. I don’t apologise for them. Joe walked those roads too, striving for the perfection.

Legend has it that before beginning the fighter-trainer relationship that would help define him, Louis worked with one Holman Williams, then a promising professional from Detroit who boxed mainly out of Michigan. Williams, soon to be one of the greatest fighters ever to have lived, would never scale the championship heights as did Louis but nevertheless is credited by some with supplying Louis with perhaps the most precious gift he ever received—his jab. But Williams is also said to have taught Louis the rudiments of the defence and was supposedly the first man to encourage Louis to punch in combination. “Don’t throw one punch at a time and wait for the guy to fall,” Holman is said to have urged Louis. “Hit him again!” Passed down to us by the victim and those lucky enough to be in attendance comes the description of his first knockout combination, thrown by Louis at amateur Joe Thomas at the Detroit Athletic Club in 1932. A double jab was followed by a right hand to the body before the teenaged Joe Louis closed the blinds on Thomas with another right hand to the temple.

But his trainer for his move into the professional ranks, Jack Blackburn, would still have his work cut out for him. If Holman Williams was to be an unlucky fighter, Blackburn had written the book on it. One of the most brilliant boxers of his generation he had shared the ring with both Joe Gans and Sam Langford several times, getting the better of each at least once. But the fight game had not been good to him. In between matching the greats and the giants he faced in his time boxing as a lightweight and welterweight, Blackburn found time to find the bottle and find trouble. He was a bad, dangerous man with a dangerous heart.

When he first set eyes upon Louis, he famously sent him away saying, “a coloured boxer who can fight and won’t lie down can’t get any fights. I’m better off with white boys who aren’t as good.”

He changed his mind when he saw Louis punch.

“He was likely to trip over his own feet, but he could kill you with that left jab. I figured, man, if he can hit you that hard with a jab, wonder what he can do with his right?”

What Louis needed to learn from Blackburn, more than anything, was how to move. How to get balanced, how to move, how to box. He knew how to punch, but he didn’t yet know how to fight.

“Boxing is built upon punching and footwork,” says How to Box. “If the stance is too narrow for balance, move the right foot a few inches to the right to widen the stance; if too wide, glide the right foot forwards a few inches. Don’t lock the left leg but keep it straight.”

Freddie Roach described Joe Louis as the “best textbook fighter of all time.” Here we see the first great foundation of that inch-perfect style. Louis hardly ever made small adjustments with his left foot. Watching him, I sometimes get the impression he would prefer not to move it at all. His left jab is always perched over that lead foot, ready to be thrown. Many of Joe’s critics accuse him of being robotic, stiff, of lacking dynamism in his footwork. This is not a criticism without basis, but nor is it the whole story. He sacrifices dynamism upon the altar of destruction; he trades footspeed for handspeed; he swaps a natural establishment of range for naturally being in position to punch—always.

The description of footwork in How to Box is so simple but to see it in action is to understand why simplicity is so often more akin to genius than complexity. Louis does as he describes, leading with his left foot, “a few inches at a time, with the right foot following, always maintaining a proper stance.” Louis almost never abandoned the stance Blackburn drilled into him: The right arm crooked, elbow protecting the ribs, “both arms relaxed, ready to attack or defend…chin down.”

His left hand would famously float; Louis would have that error corrected for him, mainly by Max Schmeling but with more than a little help from James J. Braddock and Tommy Farr. But that stance was, for the most part, developed early and adhered to throughout a career that encountered more styles and types than any other fighter at the weight.

It was visible as early as February 21st ,1925 for Joe’s rematch with Lee Ramage. The first fight had seen Louis drop the boom with Ramage ahead on points. In the rematch, Louis would demonstrate the fundamentals that would take him to the title and then beyond. The ring is not Disney—there are no fairy tales. Every dramatic narrative is built upon the twin pillars of will and skill.

Ramage fought on the backfoot, having previously been hit many times by Louis and finding he did not care for it. As discussed, his footwork lacked dynamism, so Louis never tried to get that step ahead of the opponent. He tended not to pre-cut the ring, and avoided getting ahead of his man as he was circled. Rather, he kept his front toe perpendicular to his man’s backfoot, keeping the psychological and physical pressure firmly upon him, moving with him, the definitive stalker forcing the mistake, stressing balance both in the ring and in print.

“You must be able to move the body easily at all times so that balance will not be disturbed.”

On film, Louis dips as he moves onto Ramage, jabbing, and even when he flashes forwards driving his opponent to the ropes for the first time, Louis is not compromised. He facilitates brutal blows with his studied mobility and is within hitting distance again only seconds later. The second time Ramage comes crashing off the ropes, Louis rotates his torso as he punches, the foundations are so solid that he is able to utilise a plane of movement not seen again in the heavyweight division until Mike Tyson, at least not by a killing puncher. Tiny adjustments with the backfoot are enough to transfer his weight around his body to wherever it needs to be for the punches he is using to douse Ramage’s enthusiasm.

Ramage actually boxes well for much of the second half of the second round. He moves away, jabbing, he looks reasonably skilled, quite graceful. But Louis is so fundamentally correct that even were he not Ramage’s superior in every single way he would still be the master. He is so well balanced that he can call upon almost any punch from almost any position, whether he is dipping in and slipping a jab or moving back throwing clipping uppercuts as Ramage tries in vain to crowd him. He can commit to punches other fighters would be unable to utilize in similar positions having compromised themselves. Joe almost never compromised his fundamentals. This near perfection proved too much for Ramage after only two rounds as first a right hand and then a left hook laid him low.

Of course, there were limitations, and these were exposed by nobody so completely during the Brown Bomber’s prime as they were by Billy Conn. Conn recognized early that he would be trouble for Louis telling his trainer and partner in pugilism John “Moonie” Ray to “get me in with this guy! He wouldn’t be able to hit me with a handful of rice!” years before his first outing at heavyweight. Conn was right. Louis did struggle to hit Conn, for a variety of reasons. Most of these are related to Conn’s brilliance, but that’s a story for another day. Here we are interested in the great heavyweight champion.

Firstly, Billy’s footwork was every bit as disciplined as Joe’s. Going backwards he tended to use the same small moves as Louis did coming in, meaning that he minimized dramatic errors and dented Joe’s momentum. Louis forced his opponents to make the angles. He punished mistakes. He did not, as a habit, make these angles with his footwork, rather he made them with the virtual threat of his fists. He forced the opponent to make the angle. In and of itself, this is one of the hardest skills in boxing to master, but it does not pay to rely too heavily upon even the deftest of skills against a fighter like Conn.

When Conn did abandon his small moves in favour of big ones, they tended to be brilliantly judged and perfectly executed. Joe’s lack of dynamic footwork was exposed.

Conn was also very careful to punch Louis whenever the opportunity presented itself whilst he was going away. Grossly underrated as a puncher at heavyweight (fighting men weighing over 175 lbs. fifteen times Conn registered eight stoppages including one over Bob Pastor), Conn’s work prohibited Louis rushes.

On the inside, he set up a brick-wall defence and cuffed the champion, but his brilliance was not so prosaic. Repeatedly, Conn walked Louis in clinches, he tilted him, he pushed him to the side, he tugged upon his arms, he pushed his head into Joe’s face and chest. In short, he did anything and everything he could to interfere with Joe’s balance. He knew the importance of disrupting Joe’s foundation. Bereft of his most exquisite attribute Louis could not turn over his punches in the special way he had learned and get his power across. Conn survived those cuffing punches both on the inside and the outside where Conn’s perfect footwork and granite chin combined to make him the most elusive of targets for the killing blow. If this sounds like an easy fix, take note of the following—every fighter that tried it got knocked unconscious or something like it, including Billy Conn.

From How to Box:

“…when Billy missed me with a zipping left hook, I quickly crossed a right to his jaw and followed it by several straight rights that sent him crashing to the canvas. I had to wait for Billy to miss.”

I think Louis hits the nail on the head here. He is indeed reduced from forcing the mistake as he did in so many of his twenty-five successful title defences, to waiting for a mistake. But with Louis you would make only one.

“Clever footwork does not mean hopping and jumping around,” we learn from How to Box. “This will put you off balance and the slightest blow will upset you. The purpose of clever footwork is to give your opponent false leads…it also carries you out of danger when hurt.”

This is Louis in a nutshell: economy. Every movement has a purpose, there is no such thing as show. He is often derided for this and is sometimes compared negatively with the only other heavyweight to inhabit that stratosphere reserved for the true greats, Muhammad Ali. I don’t want to get into that too heavily here, but as a final word I want to say that in my opinion, Joe’s footwork is every bit as impressive, in its own way, as is Muhammad’s. Even if Louis had been technically capable of producing Ali’s own brand of genius, Blackburn would not have allowed it. Indeed, amongst the many other services he rendered, Blackburn took Louis down off his toes. The reasoning was simple—to perfect his balance and thereby maximize the kill on his delivery. This is what Blackburn means when he says that Joe Louis is a “manufactured killer, not a natural one.”

Louis, by moving conservatively, kept his powder dry for late round knockouts—KO11 Bob Pastor, TKO13 Abe Simon, KO13 Billy Conn, KO11 Joe Walcott—versus only three visits to the judges’ scorecards—UD15 Tommy Farr, SD 15 Arturo Godoy, SD15 Joe Walcott—in title matches.

No heavyweight had better footwork than Joe Louis given his individual style.

But having said that…it’s not why you watch Joe Louis fight. You don’t watch Joe fight for his footwork—Muhammad Ali, yes, Joe Louis, no.

You watch Joe Louis for a different reason. To quote Jack Blackburn:

“Your fists, Chappie. Let your fists be your judge.”

We’ll talk about his judges in Part 2.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers