Featured Articles

‘How To Box’ by Joe Louis: Part 3 – The Right Hand

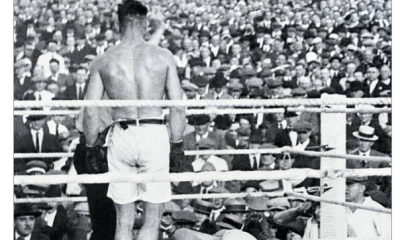

The Afro American was in Johnny Paycheck’s dressing room only minutes after his devastating knockout loss to Joe Louis in the second round of their March 1940 heavyweight title fight. Louis had been champion for three years and Johnny was his ninth successful defence. No press ever had access to a Louis knockout victim so soon after the offending punch and the sight made quite an impression.

His legs “still quivering” as his brain continued to try to absorb the catastrophic messages of disaster Louis had inflicted upon it, still fear-stricken, in a state of wonderment” Paycheck spoke with Art Carter, The Afro’s sports editor, “slowly and softly.”

“God, how that man can hit. I don’t remember anything after the first knockdown.”

The Afro American did not go easy on Paycheck in thanks for this easy access. Under a banner headline naming him “A Pathetic Figure” they went on to describe him as “a pathetic loser.” If Paycheck was pathetic, he was no more or less so than the Titanic right after it was ripped opened by the iceberg. Paycheck reacted courageously in my opinion, campaigning briefly and redundantly for a rematch.

Perhaps he believed lightning couldn’t strike in the same place twice.

For it was indeed thunder and lightning that laid him low in the shape of two of the most devastatingly effective punches in boxing history, two blows tipped by the same spear: the Joe Louis right hand.

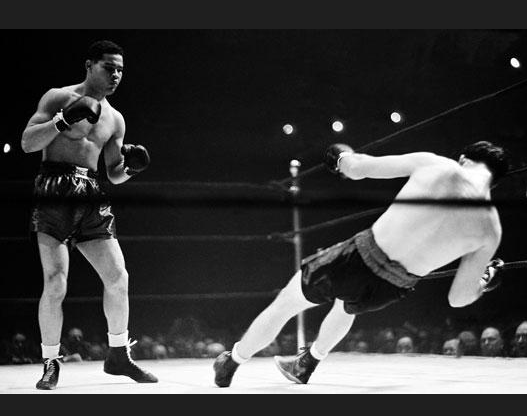

The Straight Right

The straight right hand that won Joe Louis the heavyweight title of the world drove Jim Braddock’s gumshield through his top lip and opened a wound that would require twenty-three stitches. A crimson stain “a foot in diameter” spread across the canvas as the referee tolled off the ten. Louis had thrown a perfect punch by the highest of standards—his own.

“The straight right is one of the most dangerous blows in boxing,” says the Joe Louis manual How to Box. “It is always preceded by the left lead and carries lots of force.”

Louis had indeed preceded this murderous straight right with a left hand and it is an interesting one. Written up in the press almost exclusively as a “left to the ribs,” this is how the punch is generally described even in modern books on both Braddock and Louis, when in fact Joe throws a left hook at Braddock’s left bicep. At the beginning of the action, the champion is guarding against the murderous right hand with his left hand held high, running interference through Joe’s arch of attack. Whilst Louis probably could have pecked a right hand across that left, he couldn’t have thrown the punch exactly as it is described in How to Box without compromising his position. The hook Louis threw was far more devastating than the reported shot to the ribs and I do not believe for even one moment that this was a happy accident. Louis positions himself for the left hook – readers of Part 2 of this series will note that the punch is channelled primarily through Joe’s right leg—and then throws it within the parameters of his kill-zone, defined by the limits of his balance, which will be familiar to readers of Part 1. Braddock has taken no evasive action. The punch to the biceps does not seem to alarm him.

But it should have. It allowed Louis to commit to the mechanics of the straight right hand with impunity.

“Shift your weight to the left leg and wing the right side of your body forwards, driving your right fist straight out.”

A note must be made here of how easily Louis is able to transfer the weight to his left leg from his right behind a left hook. As Louis comes forward behind his left he transfers from right to left with naturalism. There is no moment for adjustment between the left leg taking the weight of the hook then the straight right, as described by Joe Frazier (see Part 2). Louis’ straight right is a fire that burns the oxygen the left hook produces rather than a punch that hinders it with minor reorganisations. It is the most natural pairing imaginable and no other heavyweight in history, to my knowledge, throws these two punches in this manner.

“Try to drive through your aim, and not just at it.”

After leading with the left, Louis would often cock his right hand in a salute to his intended victim, his elbow still holding position at his ribs whilst the right pointed straight to the heavens before launching it forwards at the exact moment he transfers his weight. This creates a wind-up that deals almost exclusively with straight lines. The title-winning right hand was such a punch, but Louis never made do with impact. This perfect punch ripped through Braddock’s face, scarring him for life, continued through the target and down, terminating finally at his hips, perpendicular to his thigh. His head remained poised though, maintaining a rigid balance through his lead leg and torso—he looks briefly like a pool player about to attempt a particularly tricky shot—and then Braddock is falling bonelessly to the canvas, seemingly in four separate pieces, wet and lifeless but curiously unruffled, a child counting out the 100 for hide-and-go-seek. Whether you believe Braddock when he said he could have gotten up but “saw no point” or the newspapermen at ringside who deemed him insensible, it is hard to doubt that Braddock wouldn’t have risen even if the referee had counted to such a number himself. All agreed that the punch was amongst the loudest ever heard at ringside, the audio and visual combining to make The Cinderella Man seem the victim of a gunshot.

Such punches are rare for most fighters, but not for Louis. Returning to March of 1940 and the Louis destruction of Paycheck, the first knockdown is the result of a similar blow. Only seconds into the first, Louis had bundled, jabbed and battered a clearly intimidated Paycheck back to the ropes. Then, the right. As a punch it is not quite the equal of the one that ended Braddock for several reasons. Firstly, the leading jab missed the mark, reaching the point of Paycheck’s chin but failing to get over as the challenger pulled his head back and to his left in the moment that Louis pushed forwards onto his left foot, firing his right. Having failed to get his man under control with the jab, Louis found himself fully extended with the right resulting in a lack of the follow-through seen on the title-winning punch. Instead of driving his whole forearm though a rebounding opponent who has just been jabbed, he got the point of Paycheck’s chin and another inch whilst his positioning is clearly slightly off as the challenger has managed to edge his way outside of the straight-armed portion of the champion’s kill-zone. The vibration jolted the fallen fighter all the way to his ankles. This, a less perfect version of the Louis straight right, is the punch that separated Paycheck from his memory. Likely a blessing, he never would be able to recall the moments between his bravely regaining his feet and the painful journey to the dressing room where he was able to express his wonderment to The Afro American.

Up at nine, Paycheck is driven to a neutral corner, but has the wherewithal to block the next lightning Louis right hand. Recognizing his man is ready to be taken, Louis tries to set up a second right hand with a left jab. The straight right is often the finishing punch of choice for the Brown Bomber, although the left hook he tags on behind it for an effortless three-punch combination is a nice insurance policy. Paycheck avoids being stopped here by jabbing his left into the air creating a break with his own forearm which he’s able to apply to the Louis right as it zips past—this transforms the punch from a scalpel to a club and Johnny is able to survive.

Somehow he found his legs for the second round but his footwork was skittish. Gliding, clever footwork is arguably a part of the recipe for success against Louis but static small moves and feints do not impress him. Any boxer moving his feet but remaining in the kill-zone is playing right into Joe’s hands. He is a fighter that is programmed to destroy what is in front of him and the details are not particularly relevant. This mistake had cost Paycheck a nightmare start, and that pattern was set to continue. Remaining disciplined, Louis jabbed his opponent back keeping himself firmly in range but throwing only a probing left hand for the first few seconds, working on his timing before firing, at thirty-one seconds, the punch he had been brewing since the bell for round two.

It was all the more shocking for the fact that he had been “shufflin’ Joe” only seconds before, moving forwards in those small, measured steps, looking like the fighter some casual fans have come to misunderstand, especially post-Tyson. These gradual moves, these narrow approaches, these “shuffles” are the equivalent of Tyson’s menacing bull-rushes. They are bought with less energy but are layered with just as much menace and require nothing like the admittedly impressive physical acrobatics Tyson is forced to perform to close the distance.

As a punch, it may be even more perfect than the one that pole-axed Braddock. Just as he did then, Louis gets all his weight onto his front foot and follows through all the way, his forearm running horizontal to the black strip on his trunks before it comes to rest as Paycheck is rocked all the way back on his heels before collapsing at Joe’s feet, flat on his back. Louis engineered the punch so that Paycheck was circling into it as it landed, making it even more calamitous to the victim’s senses, a veritable iceberg of a punch, un-survivable for even the unsinkable.

I say engineered and I mean it. There is a final adjustment of the feet as Louis lands the jab that unlocked the final gate keeping him at distance. Coming that little bit closer allowed Louis to get outside Paycheck and drive his right through his victim’s left jaw and on as the recipient moves to his left. Throwing the punch without the adjustment would have seen him land straight-down-the-pipe on an opponent who is going away, still possibly lethal for a man as hurt as Paycheck but perhaps not the ultimate in killing punches, which is what it became as Louis made that move inside. It seems a small thing, but it is hard to teach and hard to learn and it requires both a cool head and sublime technique to execute. It is the difference between being a good puncher and good technician and a great puncher and great technician.

But in a roundabout way it reveals a weakness in the punch—and in Louis.

The killing field for Joe’s straight right is extremely narrow. As stated above, finding comparable punching technicians is not easy but as an out-fighter, the great strawweight champion Ricardo Lopez is perhaps comparable. Nothing like Joe’s equal as an infighter or short arm puncher, at distance the little man executes in combination as well as anyone and although he lacks the killing power of Joe’s straight right, I would consider him more flexible. He found ways to reach with the punch, to stab with it. He can be seen using it as a reverse jab. Most of all the width across which he is willing to throw it is much wider, his targeting for the punch is less impacted by tunnel vision. Louis has to bring his opponent into a very specific kill-zone to activate the trigger for that punch. He is arguably too much the perfectionist. He lets opponents get away—he let Billy Conn get away for a spell —because Conn could read and stay out of the narrow cone where the Louis straight gets lit up in.

For the knockout of Johnny Paycheck Louis used a covering jab and footwork to engineer an opening two inches across and then landed a technically flawless punch on that opening thereby creating a finisher which almost no fighter in any era would have survived. That is wonderful skill, and it must not be forgotten or minimized. But if there was a flaw in the punch it was the same flaw that would dog Louis for his entire career and beyond—that he was too specific. Whilst the beautiful improvisation of a left hook to Braddock’s biceps in order to facilitate a clear path for the narrow trench the straight right needed can dispel notions of stiffness in his boxing to a degree, Louis still needed a dirty counterpart to this precision punch.

The rolling thunder.

The Right Cross

What How to Box calls the right cross would most likely be referred to today as the overhand right. But as the great man once said: “What’s in a name?”

How to Box: “In order for the right cross to have the proper effect it should be remembered that its success depends upon the speed with which it is carried out.”

By any other name we recognize this as truth. The overhand right, the right cross, whatever it is named, the slower version is an open invitation to a counter. Of all the punches it is the most difficult to neaten up due simply due to the natural arc. Whilst every other punch tends to work in terms of the distance between point A and point B where A is the fist and B is the target area, the right cross travels a longer path as a consequence of form.

“Assuming the proper stance,” Joe Louis and ghostwriter Edward Mallory continue, “bend your body slightly forward from the waist, then throwing your body power into it, bring your right arm up, over and across (making almost a complete semi-circle).”

In 1937, Bob Pastor had boxed ten rounds with Joe, making the scheduled distance. Although he was soundly beaten, gaining one round on the two judges’ cards and the referee giving him nothing, Pastor celebrated like he had won the fight and the image seemed to resonate with the public. Pastor gathered himself for a shot at Joe’s world title in late 1939. Louis had been frustrated if not befuddled by Pastor’s tactics in the first fight and was determined to stamp his authority early in the rematch. The right cross was to be his weapon of choice.

Pastor’s tactics are interesting because they are a more realistic version of Paycheck’s later tactics, and, I would argue, part of a double foundation for Billy Conn’s strategy against Louis (along with some of the tougher lessons Fritzie Zivic taught him). Showing genuine mobility rather than Paycheck‘s queer half-feints and a sharp offense when Louis steps into range is a very reasonable strategy on paper. Unfortunately, Louis had already measured his man in that first fight and Joe and Chappie Blackburn had their tactics in place. Louis prods with his jab, an almost feint, the blinder as the old-timers called it, before slashing with his right cross. Louis doesn’t fight for position or use the left as a covering measure to reposition or to swat defensive ramparts out of the way; he uses it as a distraction, a killdeer bird, a lie, a message that the attack is weak.

The right hand he throws behind it is a punch far less fussy than the straight. It doesn’t need to be nursed into position and is the dirtiest punch in the Louis arsenal from the technical perspective. He lands it less than a minute into the fight against Pastor in 1939 behind the flapping pretty-birdy left. Pastor took it high on the head which likely saved him from an immediate count. Sagging into the ropes with his back to the camera, Bob’s expression is not revealed but he does seem to pause for a moment in consideration of the hardest punch Louis had landed on him up until that point—not even the punches Joe managed to get across in the first fight had prepared him for that one.

Pastor comes back at Louis and they maul momentarily before Joe, without taking a step back or to the side, makes space for another cross. It’s a reactive punch, thrown in answer to the tiny amount of room Pastor provides as he fights for his own balance. Louis follows all the way through on this punch, just as he does on the straight, his hips turned eighty degrees, Pastor turns with him under the force of the blow and as the punch finally comes to rest the two are looking away from their own fight, each of them looking out across the ring and into the 33,000 strong crowd before Louis snaps back into position and Pastor crumbles to his knees. How to Box insists that you throw the punch “with all the energy and strength you possess” and Joe commits to that tenant with enthusiasm, but what is displayed here is his continued control of total balance even whilst following through on such a punch. On the rare occasions his balance is compromised it is generally this punch that has caused the blip. But for the most part he arcs the punch as he describes, rockets through the opponent (or even misses) but remains welded to the canvas, his torso returning smoothly to front and centre after the follow-through. Watching the great heavyweights throw this punch one comes to understand how rare a talent this is. Even men like Dempsey and Tyson, compact power-hitters who also trade off balance and speed, can struggle behind.

But for all this, Pastor is up at one, Louis closes quickly and treats him to a straight right—behind a jab, naturally—which doesn’t quite make the cut as a Louis punch, appearing to hit at rather than through his man. This time Pastor gets up at nine and although he looks in control of his faculties as he hobbles back to ring centre streaked in resin, he looks very much the new boy at school, unsure just how far his new playmate is willing to go in this dangerous game. Louis gives as brief an answer as possible throwing two rare lead right hands to drop Pastor for the third count, but Pastor is running from these punches now and Louis is not catching him clean. This is where Louis really relies upon the cross. It’s a barrage punch he can throw at a retreating target, one that can’t be baited into contesting space or trying to punch back. If he was to rely upon the straight right hand in these situations, his right hand would become a non-factor against a hurt or fleet-footed opponent.

At the beginning of the second Louis tries both the straight right, to no avail, and a clipping hook which gets home without the desired result. After that he goes back to his money punch when up against a runner, rolling in the thunder. These aren’t broadsides, it’s not like Joe’s dirty punch is anything other than compressed, succinct, but it’s targeted in a less specific fashion, there’s no self-enforced flight-path or perfection bought with multiple preliminary moves. He just lashes them out there, catching Pastor high on the head with the first one, sending the smaller man on the run for nearly a full minute during which barely a punch is landed. Louis stalks him patiently and when Pastor finally tries a serious punch, a jab, he parries, then shows the challenger that birdy, that half-formed jab again and all of a sudden Pastor is on the ground again looking up.

Louis still requires patience to land, but it is telling that in a round where his fleet-footed opponent spent almost the entire three minutes on the run Louis threw more crosses than he did power punches of any other kind.

Pastor survived the second and spent most of the rest of the fight on the run, aside from the eighth, where he mounted his only offense, arguably winning that round. Louis had limited success but did well enough that he was able to go back to his corner at the end of the tenth and tell Blackburn, “The next round is the one, I’m going to get him.”

Pastor had indeed tired, and he made his fatal mistake within seconds of the restart, trying to jab and then move across Louis to his own left. Louis threw a covering left and then brought the right hand over as Pastor moved. In the end it was almost too easy. Pastor collapsed backwards like his ass suddenly weighed two metric tons and Louis had fulfilled his prediction.

“I didn’t even see the punch coming,” remarked the beaten challenger post-fight. “The next thing I knew the referee was counting nine.”

They belong together these two punches. If Louis had just been armed with the laser-guided straight right, he would have spent much of his career being out-maneuvered. Had he been armed with just the cross he would have visited with the judges more often, likely to his detriment. But they intertwine to create a right-hand offense that I’d consider unparalleled. If Louis has a tiny handful of betters where his jab is concerned and if there is a serious argument to be had regarding the status of his hook, there are no peers to his right-hand offense at his weight. For all that fighters like Foreman and Lewis who came after him were bigger and stronger, nobody has ever put together the fundamentals of great right-handed punching like Louis—and we haven’t even come to what made him really special yet, the way he wove these different punches together.

We’re getting there, I promise. The series is now at the halfway point. Next up for us, inside. Getting close and personal is the last thing you wanted to do if you were actually in the ring with Louis, but it should be safe for us. And we just might learn something.

The photo: Joe Louis Collapses Johnny Paycheck

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More