Featured Articles

How To Box by Joe Louis: Part 2 – The Jab and the Hook

In the build-up to Rocky Marciano’s first confrontation with Ezzard Charles, The Miami Herald cast an eye back to The Rock’s heartbreaking 1951 destruction of Joe Louis. In an article entitled “Louis Jab Hurt Rock, Boxing Bothers Him,” the newspaper recalled the testimony of Arthur Donovan, who refereed some twenty Joe Louis fights in his storied career. Donovan talked “half fearfully” of the Joe Louis jab and his concern that the Bomber would one day catch someone moving in, chin up and that the Champ would “break his neck.”

Everyone knows that Joe Louis is one of the greatest punchers of all time, that the unparalleled mixture of speed, power and accuracy combined to create one of the most devastating offensive machines in history, but his jab is now somewhat forgotten. Whilst YouTube and similar sights bless us with hours of boxing footage and allow a new generation to discover the ruination Louis wrought upon his opposition, these highlight packages often stress power punches and knockouts at the expense of the techniques that buy these scintillating moments—not least the jab.

Well, Louis did hurt Rocky Marciano with the jab. He hurt everyone he ever fought with the jab. Although, at 76 inches, Joe’s reach is two inches shorter than perennial peer Muhammad Ali and three inches shorter than a modern giant like Vitali Klitschko, I think it rests comfortably amongst some of the best jabs in heavyweight history. This was certainly not in question in his own time, the press labeling it “a piston of a punch,” “a brutal blow,” “Joe’s best punch” and according to the same Miami Herald article that recalled the discomfort it aroused in the era’s most preeminent referee (not to mention Rocky Marciano), “a punch that could rock a man back on his heels.”

And his left hook wasn’t bad either.

The Jab

“The left jab is seldom if ever a knockout blow,” says the 1948 British edition of How to Box by Joe Louis, “but many bouts are won by the skillful use of it. It is used to keep your opponent off balance and create opening for your more powerful blows.”

Anyone who has read the first part of this series, The Foundation of Skill, won’t be surprised to read that Joe Louis stressed disrupting the opponent’s balance as much as he stressed maximizing his own and it is indeed one of the major benefits of a busy, correct jab. Joe’s was absolutely correct and in the early phase of his career this is demonstrated beautifully in his desolation of Max Baer. Arguably his most frightening display of concentrated punching power, the fight is facilitated by Baer’s granite chin, which allows Louis to continue delivering crushing punches long after most men would have been under the care of the ringside doctor. But the jab is the punch that defines the fight.

It is also the only punch Joe throws for the first minute, underlining his technical maturity and reliance upon the punch Holman Williams drilled into him several years before. Film makes these punches appear extended or glancing, but these are the same punches that James J. Braddock described as a series of “light bulbs exploding in your face.” Louis has Baer under control from the first minute, and when Max finally throws his first punch, a leaping right hand that misses by more than a foot, Louis had already landed four jabs and a winging uppercut to the body (one count would have Louis missing just two punches the entire fight).

Moving away from the wild Baer but now sitting down even harder on the jab, Louis is clearly taking the advice in his manual to “jab through the mark, not at it, this will give you a follow-through effect.” He threw thirty-six assorted jabs in that first round and he threw them with wonderful variety mixing body blows with shots aimed at Baer’s mouth and higher on his head. He varies the speed of the jab beautifully, a skill all but lost today, he varies the power judiciously and in keeping with a wider tactical theme, for example throwing rangefinders as he begins to circle before sitting down on the snapping punches as he counters Baer‘s own jab, landing the shots that left Baer looking “like an Apache wearing war-paint” according to one writer.

Thirty-six jabs, and only a handful of other punches, but by the end of the round, Baer is all but beaten.

It is deeply ironic that what was the night upon which Joe’s jab matured to such devastating effect, he also happened to put on his first immortal power punching display. The jab is the punch that puts the “box” in “box-puncher” but Louis, as always, eclipsed his own skill with a display of violence so terrifying that it prompted Paul Gallico to write in The Daily News, “I wonder if his new bride’s heart beat a little with fear that this terrible thing was hers.”

The jab’s excellence is built primarily upon skill. It is not a punch that requires great speed to land quickly or great power to jolt the opponent. It can be the shortest punch, often travelling the shortest distance, from the lead hand to the head of the opponent boring in or from the shoulder of the fleet-footed matador trying to place the bull-rushing pressure-fighter under control. But like all punches, natural gifts help to cover shortcomings in technique. For Louis, proof of the perfection of his jab comes not on the night he met Baer, when the beginnings of his greatness were beginning to be understood, but many years later.

In August of 1951, broke and fighting only for the money, his speed and power having deserted him, a few pounds heavier than he had been in his prime, balding, trying to come back from his own failed comeback having already lost to Ezzard Charles more than a year earlier, Louis was embracing every single cliché that exists for a washed-up pug when he re-matched Cesar Brion.

At the opening bell that night, Brion bought with a brush of his shoulder what other men had paid for in blood and concussion in the previous two decades, bullying Louis back to the ropes as if he were nothing. But upon extracting himself, Louis goes directly to the jab and just like he did against Baer all those years before, he almost immediately has his opponent under control. His jab has evolved, just slightly, and he often snaps it up slightly, driving Brion’s head back a little more than the straight jab would, a heavy, thudding punch. Almost every time he lands it flush, Brion takes a step back, blinks, and thinks about the punch sportswriter Bill Corum called “the stiffest and surest jab the ring has ever seen.”

Brion tried to solve this punch by dipping deep and coming up with his own punches or showing head movement. Louis, by then a canny general, just hit him when he came up or when he stopped moving, now shooting the jab straight down the middle, his unerring accuracy and technique yet to desert him. The punch means Brion is reduced, on the outside, to throwing single shots, and even then reluctantly, as Louis tends to hit him with a jab either side. In the final round, Louis landed his first real burst of punches but he also threw twenty-six left jabs. This would leave him just outside the top ten for jabs thrown per-round in 2023. Joe Louis had a great jab, one of the best at his weight. It was so good he could beat ranked fighters with that punch alone, control ranked fighters with that punch alone. Perhaps it should not rank alongside the very, very best in the division and it seems likely that he could have been out-jabbed by the great technical giants, men like Sonny Liston and Larry Holmes, but I believe these may be the only fighters who I would rank clearly above him in this department. For various reasons of technique, accuracy, persistence, incredible variety and most of all the openings he would carve and the traps he would set with it, Louis can be ranked alongside the other jabbing behemoths in the open class, men like Wladimir Klitschko, Muhammad Ali and Lennox Lewis.

Louis, like these men, was a fighter who could win a fight “on the jab alone.”

The Left Hook

“The shorter this blow,” says How to Box, “the better the effect.”

This is a summary of the Louis offence spoken specifically about the left hook. Joe’s hook was at its absolute best when he threw it downstairs and we are going to look at his body work in detail in Part Four, but when he went upstairs it was his shortest power punch. In his second title defense in 1938 against Nathan Mann, he proved it an unusually flexible punch, too, and it would remain the most varied and improvised finishing blow in his arsenal long after the press had begun criticizing him, in some cases justifiably, for being a “robotic fighter.” Louis fought along disciplined lines, operating almost exclusively in a given kill-zone, working to bring that kill-zone to the opponent or the opponent to that kill-zone but usually in pre-determined, technically proficient ways. Against Mann though, as the broad-shouldered challenger rushed him for the first time, Louis propelled himself sharply back and away. His left foot no longer in touch with the canvas, up on the toes of his right, Louis corkscrewed a whipcord of a hook from his loosely hanging left hand. This punch illustrates two things concerning the Louis hook. Firstly, the positioning of his jab-hand and the frequency with which he throws that punch makes it a blow he can disguise, a natural counter. Secondly, it underlines the strangest fact of all concerning the Louis left hook: he drove it with his right leg.

In Box Like the Pros, his own, more detailed manual on boxing, Joe Frazier is very clear on how the left foot should be used when throwing the punch that made him famous. It is to be kept firmly planted; it is to drive the punch; when you bring your left hip around to follow through keep the left foot planted; “adjust your balance as you follow through with the punch, move a little if you have to”; but keep the left foot planted.

Similarly, Bernard Hopkins stresses this left foot drive:

“I dip a little to the left and rotate slightly to the left, my body weight shifts from both legs to mostly the left one…as I bring the punch up I’m driving with the left leg and at the same time bringing my hips around…”

In How to Box by Joe Louis, the transfer of weight is through the right leg.

“From the proper stance…turn your body to the right, shifting your weight to the right leg, throw the left arm in an arc to the opponent’s head. Make sure to hit through the mark and not at it.”

This is not unheard of. I have been told that Ray Leonard threw and even taught the left hook right legged, or rather he was not a slave to the left leg and preferred to gain the leverage where he could. That sounds like Leonard, but it doesn’t really sound like Joe. It isn’t in keeping with Joe’s reputation for technical exactitude and this right foot pivot interested me.

Later in the second round against Mann we see Louis push through with the right foot for the hook once again. As Mann is finally baited forwards upon seeing Joe with his back to the ropes, the Champion throws out a lightning-fast softener, comes the other way with a clubbing punch to the side of Mann’s head before striking out with the punch the trap was set for, a left hook that combines the best attributes of the other two punches. Once more, Louis is turning through his right foot. Mann is stunned and almost goes to his haunches, his face an open question mark, his steps a trickling stream. It is a double blow for the men surprised by Louis, they come forwards as the aggressor into his kill-zone having landed some token punch (in this case a hard right hand) to which Joe gives ground before nearly taking the opponent’s head off with punches. And what punches! Louis still has his elbow crooked in the defensive position when he throws the first left hook, he’s throwing it across that famous and oft-quoted distance, mere-inches, perfectly disguised, impossible to see coming, the power generated in a fashion so brilliant and dynamic that they are almost beyond technically correct; that is, nobody would ever try to teach a fighter to punch in this fashion because it just doesn’t occur to most trainers that the person standing in front of them hitting the pads is the fistic equivalent of a primo ballerina. But it is perfect. The second punch was more fully born but it is still a mere forearm’s length in flight, punching all the way through the target.

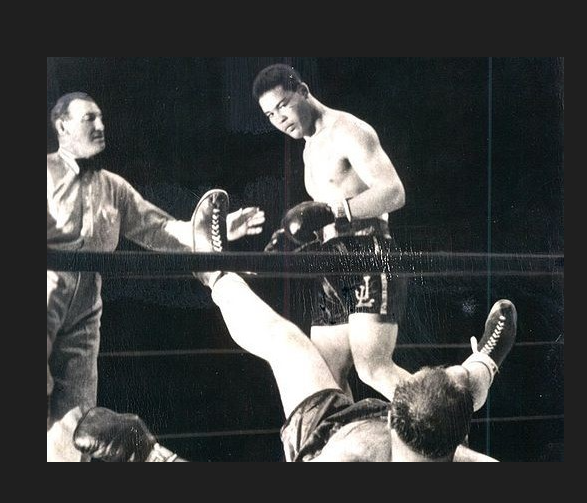

Two more left hooks score the first knockdown of the fight just seconds later. Mann flapped after he felt the first one, arching back and to the side, but Louis looked like he was hitting a static heavy bag as he delivered and calmly made his way to the neutral corner. When the action resumed, Louis walked up to Mann and hit him with two more, one up, one down as the gutsy Connecticut man sagged on the ropes. The bell saved him and he wandered off to a neutral corner of his own, confused by the absence of a stool. The inevitable occurred at 1:56 in the third.

I’d nominate Mann as Joe’s best hooking performance, but it did not contain the most devastating hook he ever threw. Louis saved this dubious honour for a fighter who infuriated him personally more perhaps than even Max Schmeling, “Two Ton” Tony Galento. Employing the unfortunate language he has remained famous for, Galento (pictured on his backside) managed to find his way under Joe’s skin, before adding injury to insult by dropping him with a left of his own in the third. In the fourth, Louis sent over what may have been the punch of his career, a left hook which Joe says “started [Galento’s] mouth, nose and right eye bleeding.” There is a beautiful series of photographs in How to Box showing Louis cock and wing in that punch. We see him adjust it in flight so the knuckle part of the glove connects with the point of the chin before Louis follows all the way through, his left hand resting calmly in front of his right, Zen-like. As Galento is falling, he too is Zen-like, but for different reasons.

Also of interest: we see Louis pivoting through his right foot. Why? Perhaps it was just the way he threw them and when his trainer Jack Blackburn saw how well they worked he refused to adjust them. Perhaps Louis had a strange ambidextrousness where his left hook was concerned and like Ray Leonard he was able to generate torque with either one of his legs dependent upon circumstances; there do seem to be times when he is driving through his left.

Or just maybe, Joe Louis didn’t like the adjustment Joe Frazier describes at the end of his procedure for throwing the perfect left hook: “Adjust your balance as you follow through, move a little if you have to.” Maybe he found a better way to stay balanced. A more correct way, for him, to throw the punch. Stop—rewind that. There is no “better way” than Frazier’s way when a fighter is throwing a left hook, right?

Right?

If this question makes you uncomfortable, keep an eye out for Part Three. We’re going to talk about the right hand. We don’t have to worry about any peers butting in for that one.

None exist.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

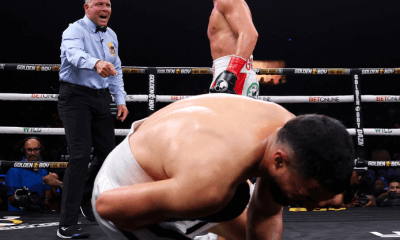

Featured Articles6 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons