Featured Articles

‘How To Box’ by Joe Louis: Part 4 – Bodywork and the Uppercut

There is a certain type of Joe Louis opponent. He is not defined by the style with which he boxes, his size or his temperament. What binds these men together is that they gained the attention of Joe Louis as adversaries. Think of men like Jersey Joe Walcott (more of whom in Part Five), Max Schmeling and Billy Conn. At a given moment it dawned upon each of these men for the first time that Joe Louis had really noticed him. So many fighters who had the bravery to take to the ring with him were interchangeable. Paycheck, Dorazio, McCoy, Roper, Lewis, these men did not stir in Louis even the merest suggestion that he was doing anything other than what came naturally; he was a shark that had come to feed.

For each of those that troubled him long enough for him to notice them in a more fundamental way, a way that called for studied consideration, the moment of realization came at different times. Walcott learned last, as he took to his heels and ran from Joe in the final round of their first fight. Schmeling likely realized in the moment his back was broken by a Louis punch in their rematch. Conn recognized his predicament as he came to from an inexplicable reverie in his dressing room before his own second fight with Louis long enough to mutter, “this will be the worst fight ever” and trudging to the ring with the same expectation of a positive outcome as a man heading to the gallows.

And what of Arturo Godoy, the Chilean jack-in-the-box bruiser who extended Joe Louis fifteen rounds in February of 1940, when did he realise he had drawn the special attention of a champion who always wrought terrible havoc on the fighters that caught his eye? History doesn’t record the exact moment but if I were guessing I would speculate that it was whenever he learned that Louis was working in training specifically to nullify the Godoy style. According to The San Jose Evening News, Louis had been working with sparring partners who were told to recreate the “croquet-wicket stance” of the Chilean contender whilst Louis worked upon tactics to nullify the awkwardness of an opponent who had split the decision in that first fight.

It seemed Godoy had caught the attention of Jack Blackburn, too.

After the debacle that was the first Schmeling fight, Blackburn tended to satisfy himself with a solid training camp that saw Louis turn up and do what he was told. Blackburn was hired in part because he was tough enough to handle a man with Joe’s astonishing gifts but by the time the German had been set up for them, a problem that even canny manager John Roxborough could not have foreseen emerged—Blackburn had gone soft. This embittered, giant-killing, murdering alcoholic had fallen so completely for Joe Louis that he couldn’t bring him to heel. Blackburn complained bitterly to the Norfolk Journal and Guide about Joe’s new relaxed attitude to training.

“You newspaper men have made him think he can just walk out and punch anyone over and that Schmeling’s the easiest pushover of the lot. Well Joe’s likely to get hit on the chin by one of them Schmeling rights…”

The trainer’s total prescience in predicting not just Joe’s downfall but the specific mode of that downfall is arguably the best thing that ever happened to Louis. Little Chappie had no more problems getting Big Chappie to listen to what he was told thereafter. Louis worked in training, only pausing long enough to let Blackburn taste the sweat on his shoulder when, after weighing the salt content, he would indicate whether Joe should continue or hit the shower.

Whilst they talked about the specific strengths and weaknesses of the opponent, Blackburn did not have a modern-day trainer’s access to film or internet and Godoy had not boxed in the United States since 1937. In early 1940, Blackburn and Louis had been caught by surprise and had been run close. They would not repeat that mistake four months later.

“I don’t like other fella to make me look bad,” said Joe. “They usually find out I don’t like it.”

Another Joe Louis punch was about to come of age.

The Uppercut

“Perhaps the shortest of all blows is the uppercut.”

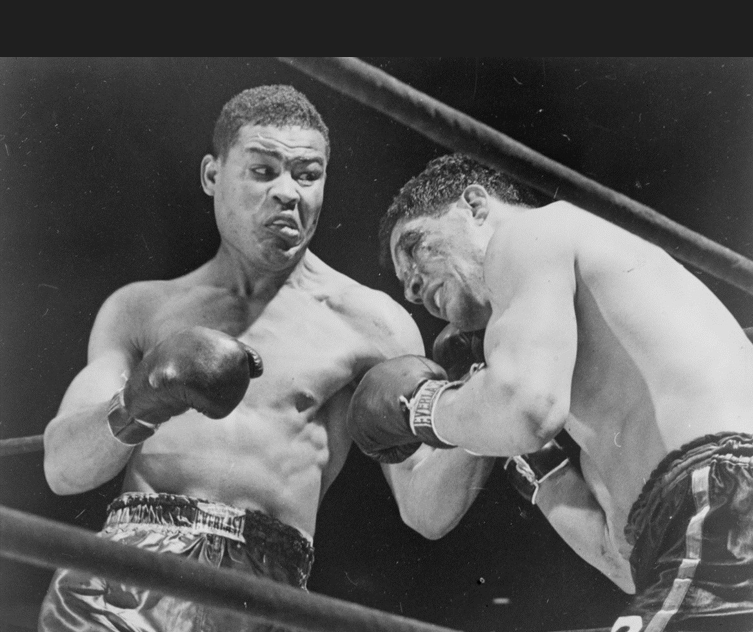

This is the first word on the uppercut in the Joe Louis boxing manual. I hope readers are by now familiar with How to Box. Joe did indeed throw uppercuts shorter even than the narrowest of his hooks, but it was not a punch that he used to bombard and overwhelm opponents until the second fight with Godoy. The uppercut in volume solved both problems Godoy had set for him in the first fight, discouraging the headbutts Joe felt the Chilean had reigned down upon him and punishing every reckless step in his swarming attack. The punches themselves are dizzying. Louis begins with a right uppercut inside, “bending to the right and slightly forwards” as How to Box advises on throwing the right uppercut, before stepping back as Godoy (pi

Burman

ctured) tries to crowd him and landing a left uppercut/overhand right twice in quick succession, “dropping your right arm a few inches and making sure the fingers of your fist are facing your own body, bring your right arm up in an underhand arc to your opponent’s chin.”

A missed or even a landed uppercut can be an invitation to the wildest of counters because, as per the above description, it commits the bodyweight to the same side as the punch that is being thrown. You transfer the weight to your left side as you throw your left. Joe’s problem with the commitment he shows to this punch is that it makes him vulnerable to exactly the type of rushes that Godoy excels in. This, then, is why Louis is so careful to throw another punch behind it, generally his wildest, least technically fussy punch. His balance allows him to commit to this sort of plan. Imagine for a moment the practical difficulties in maintaining balance, never mind punching position, whilst being leaned upon and butted by a 200 lb. man and steering your weight right and throwing the uppercut—now add the technical detail of the second punch (see Part 3—The Right Hand). My guess is that there has been no fighter around his weight capable of making this fight plan work with the possible exception of Evander Holyfield or Ezzard Charles, who were never able to generate anything like the speed and power Louis had on these punches.

Godoy would say afterwards that these were the blows that dissuaded him from his highly publicized pre-fight strategy of slugging it out with Louis. He had lasted perhaps thirty seconds.

Going now to the fight-plan that had caused Louis so much frustration in the first fight, Godoy tried to swarm his way in from the crouch, Louis greeted him with the right uppercut to the body. The punches that come right after this blow are the ones that had made so little impression on the challenger in the first fight, but Louis has his single welcomer down pat already—the uppercut is working.

Just how much he needs that uppercut becomes apparent as the rest of the round plays itself out. Louis spoke after the first fight of his concern for his hands. Beating a tattoo upon Godoy’s bowed head, he claims to have never risked the wrath of his full-blooded straight punches in that fight—there is indeed a noted difference in the Louis jab, which Blackburn has convinced him he needs to throw with impunity in the second meeting—but the straight right stays in the holster. The other punches skit and whistle off Godoy as he burrows in, the angles are all wrong as he gets inside the arc of the left hook and even that messier cross. Whenever a near-to-flush punch finds him, he dips even lower to ditch whatever comes behind it. Through the second, third, fourth and fifth Louis peppered uppercuts into what may have seemed at the time a repeat of the first fight, but that punch was telling. Sometimes he just lifted them into the face or body of the oncoming Chilean as he mauled forwards, low-risk, low-reward punches that did a cumulative damage to his opponent. But every now and again he would turn the style on and throw the punch as it’s described in How to Box, giving it “the slight twist of the hip” that will often “send your opponent tumbling to the canvas.”

At the end of the fifth, Louis told Blackburn that his stubborn opponent was “getting soft” and was “ready to go.” Blackburn hesitated, then told Louis to keep boxing for one more round. The frustration in Joe’s work in those three minutes is there to see; it is, I believe, his worst round of the fight. He’s a shark that came to fight but is now ready to feed. Blackburn saw the redundancy of holding him back any longer, and in the seventh, Louis came to kill. The weapon of choice, of course, was the uppercut.

By the beginning of that seventh, Joe had already inflicted upon Godoy the wounds, predominantly to his left eye and his lips, that would lead The Afro American to describe him as “the worst battered piece of meat ever to walk from the Yankee Stadium,” easy to write off as hyperbole were it not for The Calgary Herald describing him one week later as “still looking like he had been hit with a meat-clever.”

Louis landed more than a dozen flush uppercuts of the perfected variety in that seventh round and to appreciate their power is to watch Godoy lose touch with his own boxing as the round ticks down. No longer fighting to contain his man he now makes half steps, turning Godoy as he goes, opening doors for one or other of those cleaving punches that cost him so little in terms of balance. The knockdown, which comes right at the end of the round, is a sight to see, as Godoy bobs twice below waist height, a bemused Louis looking on, missing with his first punch, but then straightening Godoy to almost his full height against his will on the end of first a left-handed, and then a right-handed uppercut. This is the Louis solution to the Godoy crouch in a nutshell: punch him underneath his chin until he stands up straight.

The eighth is a master class in the uppercut. Louis recognizes immediately that Godoy no longer has the balance or strength to swarm and that he is now only following. He immediately transfers his offense to the backfoot, fighting laterally and backwards making room by turns for each hand. Godoy is a rampart crumbling.

The straight right hand is finally uncorked to dispatch the gutsy Chilean, but the uppercut is the punch that solved the puzzle, won the fight, and opened Godoy’s face like a can of blood-frothed beer. The “dozens” of stitches he needed in his eyebrows post-fight likely contributed to the end of his prime—Louis had broken another one and Godoy won only four of his next twelve fights.

But he was spared the expected body punching, outside of the occasional uppercut. The press had been almost unanimous pre-fight in predicting that Louis would go to the body in an effort to “straighten Godoy up.”

Bodywork

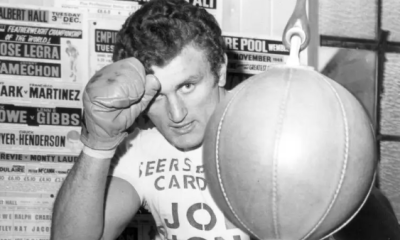

When Joe Louis stopped Red Burman with a body punch in January of 1941, the most telling reaction was surprise. Louis just didn’t knock guys out with body shots.

“For the first time in his three year reign as king of the fistic world,” wrote the Lewiston Morning Tribune, “[Louis] knocked out a rival with a punch to the body.”

The punch itself was a straight right hand, the most precise and deadly of the Louis finishers as outlined in Part Three, this time driven to the heart.

“So unexpected was it,” the newspaper continued, “that the crowd in Madison Square Garden let out an audible gasp as the Brown Bomber revealed this new way of arriving at the old result. Up to tonight he flattened 10 of the 12 battlers who had challenged the reign he began when he finished old Jim Braddock…the head punches were the crushers.”

Burman had also surprised up until that point, doing well and arguably winning the third on a hard left hand that “half turned” the champion, but in the fifth he was brought to heel, cut and bloodied before being trapped upon the ropes and very nearly broken in two.

Louis vs. Burman

“A funny look spread over [Burman’s] face,” said the Tribune of the challenger’s reaction to the final punch. “Then he toppled. He fell with his head and neck across the bottom strand of the ropes and stayed that way, moving only slightly.”

“That was just about the hardest punch I ever threw,” Louis offered post-fight.

The above remark is worthy of your consideration. Louis still had some incredible punches ahead of him including, amongst others, the destruction of Buddy Baer (more of which in Part Six) but his more famous single punches— the left hook against Galento that brought blood from the face of “the little man” in rivers, the cannonball right that left Braddock in repost on the canvas, the shot that brought the famous scream from Schmeling—were behind him. But Joe’s pick—or “just about”—was the body shot he threw at Burman, twelve defences into his extraordinary title run. What this tells us is that Louis is as capable of hurting a man to the body as he is to the head. The reason that he doesn’t have more stoppages via body punches is that he was every bit as much a headhunter as his single peer, Muhammad Ali. But Louis was far too drilled, far too much the perfect technician to neglect body punching in the same way. He used it as a tool to facilitate his headhunting, and so great a fighter was he that he sharpened this tool not upon journeymen as is customary, but upon two former heavyweight champions of the world.

A little under a year after turning professional with a record standing at just 19-0, Joe Louis matched not just a former world champion but a man who outweighed him by more than sixty pounds in the shape of Italian giant Primo Carnera. In the first, Louis ripped punches into Carnera’s head and Carnera did his best to grab his tormentor, closing down avenues for Joe’s more exact punches upstairs but opening up the body. In the second Louis attacked that body two-handed as Carnera’s eyes were filled by what the Lewiston Daily Sun ringside reporter described as “a look of horror.” By adding bodywork, Louis had transformed himself into a lit stick of dynamite, still possible to smother, but only to one’s detriment. He continued to mix his punches in this fashion until the fourth, during which he rested a little only to open up in earnest in the fifth.

As always, Louis is looking to land his jab, but here he goes to the body. Carnera has a serious size advantage and whilst Louis hasn’t struggled to reach him the jab is his way in. When he throws this punch to the body it is not quite as perfect or snapping as is the respective punch to the head. Louis “pumps” his left when he throws it downstairs, often taking a step to his left or straight back as he does so, a nod to his temporary vulnerability as, for just a second, his bodyweight goes over that front foot. Adding a stout jab to the chest, his offense is in motion without his having to overreach himself in any meaningful way. Carnera is understandably but ineffectually trying to maintain distance with his own jab but Louis has a dramatic advantage in handspeed which allows him to close that gap. When the Italian manages to move off the ropes having suffered a handful of Joe’s Sunday punches, Louis again returns to the jab to the body, lowering Carnera’s guard and setting him up beautifully for the feint Louis launches at around 1:50 of the round, a step inside as though he were about to jab the body followed by a shift and a clattering hook upstairs. Carnera’s bewilderment is now complete. He is guarding against a jab to the body, a jab to the chest, flashing punches upstairs and a feint off the low jab. With just two different jabs downstairs, Louis has bought himself total tactical superiority over a much larger former champion of the world.

In the sixth, a scything left hook is added to the wheelhouse right Louis dropped at the end of the fifth. This punch causes Carnera notable discomfort as it is delivered in the same fashion as the left hook to the head, short, fast and powered through the right leg (see Part Two—The Jab & Left Hook). As a rule Louis displays no equivalent to the straight right hand to the body (though he seems to have made an exception for the unfortunate Burman) but he throws his other power punches in near identical fashion to the ones he throws upstairs. For all that, they are rarer and generally abandoned when it is time for Louis to finish, although he does feint a left to the body as he prepares the giant’s coup-de-grace.

Only weeks later, bodywork played a less crucial role against another former heavyweight champion, Jack Sharkey.

Sharkey was there for Joe’s punches more than Carnera had been by virtue of his lesser size but Louis utilized a great uppercut to the body in that fight, straight through the middle as Sharkey went into his crouch, foreshadowing his eventual solution to the Godoy problem. Sharkey’s lack of dynamism and abandonment of his offense also left him vulnerable to a newfound fluidity in Louis as he went round the houses on Jack, landing a left to the head then a right to the body then a left to the body and a right to the head. But these body blows are not the eye-catching punches, and nor should they be. How to Box offers little, a single paragraph which notes dryly how body punches are liable to “weaken the opponent,” but as we’ve seen they were much more. The body punch that laid Red Burman low led him to label Louis “the killer-driller,” a nickname that may have stuck were it not for the fact that Louis had been “The Brown Bomber” for many defences by that stage. The real function of Joe’s bodywork was not to “kill” however, rather it was designed as a second front, a secondary wave of attack to confuse and stretch the opponent’s defence. Louis, like all great destroyers, understood to take the opponent’s defences to pieces. Furthermore, like all great fighters he has a defence of his very own. It is not the deeply flawed defence of legend, either. It is layered, for the most part technically sound, designed to facilitate the punches that made Joe Louis famous and the subject of Part Five.

I hope you can join me.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRamirez and Cuello Score KOs in Libya; Fonseca Upsets Oumiha

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More