Featured Articles

Joey Giardello vs. Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter and the Fight That Never Was

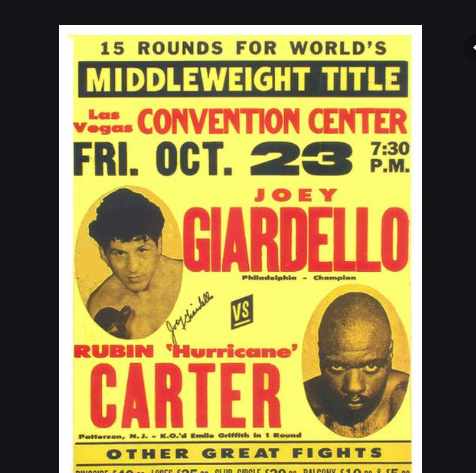

Today (Wednesday, Oct. 23) marks the 55th anniversary of the aborted fight at the Las Vegas Convention Center between Joey Giardello and challenger Rubin “Hurricane” Carter for the middleweight championship of the world.

How’s that again?

Most folks with an interest in boxing history are aware that Joey Giardello once fought “Hurricane” Carter. Many know that the fight was held in Philadelphia. And the most fervent boxing aficionados can probably pinpoint the month and year, December of 1964, Dec. 14 to be exact. But few people know that this fight had been orphaned, leaving the principals stranded in Las Vegas, as it were, scrambling for a new date and venue.

It’s odd that there’s been virtually no mention of this fact in stories about the Giardello-Carter fight because had the fight had gone off as scheduled, the post-fight life of Hurricane Carter may have taken a different path. Considering what lay ahead for him, it’s hard to think of another aborted fight that commands such a compelling “what if?”.

The Las Vegas fight was promoted by an organization called the Silver State Boxing Club. The face of the club was matchmaker Mel “Red” Greb. A Caesars Palace craps dealer, Greb had learned the business of boxing in his native Newark beginning as a teenage “go-fer” for Willie Gilzenburg who had the boxing and wrestling concession at Newark’s premier indoor sports venue, Laurel Gardens.

For a world title fight, the Silver State Club needed a partner to share the expenses and risk. They partnered with Telescript, a fledgling company that had acquired the rights to exhibit the fight at closed-circuit outlets. But Telescript, to Greb’s great dismay, was all smoke and mirrors. The company was contractually obligated to kick in a portion of the required $55,000 bond, but the helmsmen kept stalling and eventually Greb had no recourse but to bail out. On Monday, Oct. 19, four days before the big event, a crestfallen Greb told the media that the show was canceled. The gate receipts alone wouldn’t be sufficient to cover his nut.

In those days in Las Vegas, it was normative for the principals in a nationally important fight to show up three weeks before the event. The showroom or ballroom at the casino where they stayed was converted into a gym for afternoon workouts. The workouts were open to the public and the fighters were expected to fraternize with high rollers.

Joey Giardello, being the A-side guy (and the white guy) got to stay on the Strip. He and his entourage stayed at the Thunderbird. They sent Hurricane Carter downtown to the far less toney El Cortez.

According to stories in both local papers, Carter looked sensational in his workouts. He ran off several sparring partners.

One could attribute this to pre-fight hype, but hype that is especially thick is invariably layered on an underdog and Hurricane Carter was the favorite. The local bookies had it 7/5 that The Hurricane would snatch away Giardello’s title and the price was expected to drift higher.

A Snapshot of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter

In 1964, Hurricane Carter was 27 years old. To say that he had a troubled past would be an understatement. He had been convicted three times for muggings and had already spent 10 years of his life behind prison walls.

Carter was good copy for sportswriters because he was extremely well-spoken. “I regret that I was a contumacious child,” he told New York Post reporter Milton Gross. He had charisma that accrued from his menacing appearance. He was one of the first prominent athletes to shave his head bald, cultivated a Fu Manchu moustache and a thick beard, and perfected Sonny Liston’s malevolent glare.

Carter turned heads with first-round knockouts of Cuban contender Florentino Fernandez and world welterweight champion Emile Griffith in a non-title fight. Aside from those spectacular triumphs, his best win was a split decision over George Benton, a tough fighter from Philadelphia who would go on to become a prominent trainer. Benton owned a win over Giardello.

But Carter’s 20-4 pro record was unexceptional for a man accorded a title shot and three of those losses had come against marginally skilled opponents. Giardello’s boosters disparaged Carter as a frontrunner, a boxer who loses his courage when he fails to take his man out quick.

A Snapshot of Joey Giardello

Giardello was born in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn and raised in South Philly. His birth name was Carmine Orlando Tilelli. The name “Giardello” came from a phony ID, an ID loaned to him by an older boy, the cousin of a friend. It was Joey’s passport out of his hoodlum-infested neighborhood, allowing him to join the Army at age 15. The pseudonym stuck.

Prior to joining the Army, Giardello had served four-and-a-half months in a juvenile reformatory. He was the alleged ringleader of a gang of teenagers that busted up a gas station.

Giardello’s 10-round fight with Detroit’s Henry Hank in 1962 was named The Ring magazine’s Fight of the Year. But his performance in this fight was out of character as Giardello wasn’t a hell-for-leather fighter. To the contrary, he was something of a cutie; a crafty technician.

His career was a lesson in perseverance. He had 105 fights under his belt when he got his first title shot. It came against Gene Fullmer in Bozeman, Montana, a regional site advantage for Fullmer who lived on the outskirts of Salt Lake City. In a lusty match, Fullmer retained his title with a 15-round draw.

Three years later, after upsetting a faded Sugar Ray Robinson, Giardello was granted another title shot, this coming against Dick Tiger in Atlantic City. They had split two previous meetings, but Tiger, born in Nigeria, was installed a 7/2 favorite.

Counter-punching effectively, Giardello won the title, prevailing by an 8-5-2 margin on the scorecard of referee Paul Cavalier, the sole arbiter. There were only two internationally relevant world sanctioning organizations, the WBA and WBC, and both now recognized Joey Giardello as their champion.

When the Giardello-Carter fight finally came to fruition at the Philadelphia Convention Center, the deck was stacked against The Hurricane. The Pennsylvania Commission, yielding to a protest from Giardello’s camp, forced Carter to shave off his beard so that he could not use it as an abrasive in the clinches. And although Carter hailed from Paterson, New Jersey, not far from Philadelphia, he would be in hostile territory. The crowd was overwhelmingly pro-Giardello.

In the 1999 movie “The Hurricane,” filmed in black-and-white to capture the flavor of the era, Carter pounds Giardello from pillar to post only to be robbed of the decision by racially biased judges who deliberate 35 minutes before reaching their decision.

Carter is portrayed by Denzel Washington. He’s brilliant, but the movie is garbage. Fourteen of 17 ringside reporters scored the fight for Giardello who did especially well in the late rounds. (Giardello sued director Norman Jewison for libel and received an undisclosed sum in a case settled out of court.)

Hurricane Carter had 15 more fights, winning eight, before he was locked away in Rahway State Prison for his involvement – perhaps we should say alleged involvement — in a particularly heinous crime, a triple homicide at a Paterson bar and grill. He spent 19 years at Rahway, all the while maintaining his innocence, and became a cause-celebre, inspiring three books (the movie was based on his autobiography “The 16th Round”) and a Bob Dylan song. He died in 2014 in Toronto where he was being treated for prostate cancer.

Joey Giardello lost his title in his next title defense, losing a 15-round decision to four-time rival Dick Tiger, and retired in 1967 with a record of 98-26-8. In retirement, he held several private- and public-sector jobs and became known for his charity work, particularly for children with learning disabilities. (Joey’s son Carman, the youngest of his four children, was born with Down Syndrome.) He died in 2008, three years before a statue of him by the noted sculptor Carl LeVotch was unveiled in his old Philadelphia neighborhood.

Nobody seems to be on the fence when it comes to Hurricane Carter’s guilt or innocence. He was twice found guilty in jury trials, but both verdicts were overturned on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct. “Twice Wrongly Convicted of Murder” appeared in the headline of his obituary in the New York Times, but there are some folks who will always believe that justice would have been better served if his captors had thrown away the key. Regardless, the “what if?” question will never disappear.

What if Carter’s fight with Giardello had been staged in Las Vegas as originally planned? Keep in mind that Carter would have been favored. How would his life have changed going forward if the fight hadn’t imploded, the casualty of a bad marriage between a local promoter and a feckless TV partner?

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend