Featured Articles

Leon Spinks, Dead at 67, Fell Far and Fast After Shocking Muhammad Ali

No one could ever confuse former heavyweight champion Leon Spinks, who on Friday night finally succumbed to the multiple cancers that for several years had been slowly devouring his internal organs, with handsome film star Robert Redford. But achieving a seemingly impossible goal, in real life for “Neon Leon” and on the silver screen for Redford, does suggest a possible link.

It is one thing to fulfill a dream few thought possible. It is quite another, once the dream becomes reality, to enjoy the tsunami of attention that can make a sudden and unprepared star a sort of Cinderella in reverse. In 1972’s The Candidate, Redford portrayed a young and ambitious senatorial nominee who, against all odds, wins election. In the final scene, he slips out of the victory party to be alone with his thoughts. Upon being joined by his campaign adviser who tells him he has to come back to meet with a throng of journalists, the stunned new senator-elect asks, “What do we do now?”

Leon Spinks, who someday would shock the world by upsetting the great Muhammad Ali, launched his longest-of-long-shots plan to become heavyweight champion when, at age 13 and constantly picked on by older boys in St. Louis’ notorious Pruitt-Igoe housing project, he heeded the advice of a Teamster official named Mitt Barnes to take up boxing as a means of better defending himself on the street. The oldest of seven kids (six sons and a daughter) raised by his mother Kay after the father had left home, Leon proved a quick study in the pugilistic arts, if not academically. A dropout midway through his junior year of high school, he became a father at 17, enlisted in the Marine Corps at 19, and by the time his service hitch ended had won 178 of 185 amateur bouts and was fast-tracked for eventual success as a pro. He was a bronze medalist at the inaugural 1974 World Championships, a silver medalist at the 1975 Pan American Games and then a light heavyweight gold medalist at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, at which his younger brother Michael also took gold as a middleweight.

In 1994, Michael, who would go on to win both light heavyweight and heavyweight titles as a pro, recalled how he frequently got the worst of it in sparring sessions with his older brother, until the day when he proved to himself that he at least had significantly narrowed the gap between them.

“It was back in St. Louis, in the early ’70s,” Michael said. “Me and Leon were passing by this gym, somewhere we’d never been in before. Leon said, `Hey, let’s check this place out.’ There was a ring in there, and Leon found a couple of pairs of gloves. We pulled them on and went at it for three rounds.

“I couldn’t believe I was actually winning. You have to understand, Leon had always beaten the dog out of me. He always beat the dog out of everybody. Leon was the man in those days. There wasn’t anybody who could beat Leon. There wasn’t even anybody who could last three rounds with him. He used to beat me up so bad, I’d cry. He beat me like we weren’t even brothers. But he was trying to help me, in his own way. He’d say, `Mike, I know I take it hard on you, but if I took it any easier, you wouldn’t learn anything.’

“I threw off the gloves and said, `Hey, man, I beat your ass. I got you.’ And that was it. We never sparred again. Looking back, that might have been my proudest moment in boxing. I figured if I could do that well against Leon, I could hold my own against anybody. From that point on, I was a completely different fighter. I had confidence in myself.”

Maybe Michael was even as confident in his ring abilities as was Leon, who wangled a lucrative contract with Top Rank after the Montreal Olympiad while Michael went back to his old job as a janitor at a St. Louis chemical plant, where his duties included, as one co-worker later observed, “scrubbing floors and cleaning toilets.”

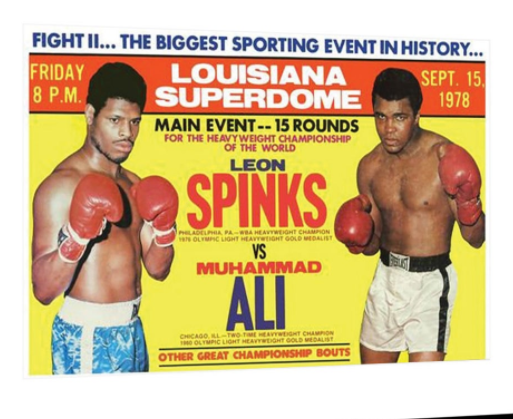

For Michael, who later joined Leon in the Top Rank fold, his star turn as a pro would come later. It arrived startingly soon for Leon, who, with just seven pro fights (6-0-1, 5 KOs), was tapped to challenge WBC/WBA champ Ali on Sept. 15, 1978, at the Las Vegas Hilton. Virtually no one gave Leon much chance to even be competitive, much less win, but the 24-year-old underdog believed he had a fight plan to get the job done, one previously authored against Ali by Joe Frazier.

“I watched him fight Joe Frazier, and I knew then I had to give him pressure like he’d never seen before,” Leon said of the punches-in-bunches he intended to throw at Ali, then 36 and as overconfident as Spinks was hopeful. “By the time I got to Ali, I knew how to beat him before I ever fought him. Then I learned the pressure of being champion.”

The shocking split decision for Spinks, accomplished before just 5,298 paying spectators, did not appreciably diminish the star power of Ali, but it made the victor an instant sensation. It also changed his life and career in ways he could not have anticipated, both good and, even more obviously as it turned out, bad. Being the new heavyweight champion and conqueror of arguably the greatest heavyweight of all time had the same effect on Leon, even more so, in fact, than winning an election he never thought he could, had on Redford’s fictional character six years earlier.

In quick order, the WBC stripped Spinks of its version of the title for declining to fulfill a mandatory defense against Ken Norton in favor of a much-better-paying, much-higher-visibility rematch with Ali, who was determined not to make the same mistakes he had made the first time around. Guys from Leon’s St. Louis neighborhood and hordes of other aspiring hangers-on sought to gain the champ’s ear, and in many instances did.

The do-over was scheduled for Sept. 15, 1978, in the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans, the lead-up to which was a spectacle of excess to rival Mardi Gras. Some 63,350 fight fans packed the arena, among them such celebrities as Sylvester Stallone, John Travolta, Jackie Onassis, Liza Minnelli, Jerry Lewis, Telly Savalas, Kris Kristofferson, Rita Coolidge and Lily Tomlin.

It was hoopla to an extent that Ali, as much as any boxer ever, could handle in stride. Not so for Spinks, who even before arriving at the fight site had demonstrated that he was crumbling under the demands of his newfound notoriety.

The late Butch Lewis, who promoted both Spinks brothers, recalled how Leon disappeared for days at a time when he should have been in the gym and focusing on the task at hand. Rumors flew that he was pub-crawling not in the comparative safety of the French Quarter, but in dives in crime-infested neighborhoods that even the local police were hesitant to go into.

“He was drunk every night he was there,” disgusted Top Rank founder Bob Arum said of Leon’s hard-partying ways. “Leon went to places our people didn’t dare go to. I’m surprised he didn’t wind up with a knife stuck in him.”

The shenanigans weren’t so amusing to highly regarded Philadelphia trainer Georgie Benton, who had been brought in to plot Leon’s strategy for the first fight and stayed on for the second, ostensibly in conjunction with lead trainer Sam Solomon. But Benton and Solomon seldom agreed on anything, and then there was the matter of Leon’s 70-member entourage, all of whom figured they merited a spot in his corner on fight night.

Shortly before the fight, Solomon told Benton that Spinks’ small army of would-be advisers would take turns working in his corner. “Sam said, `You go up one round and work and then Leon’s brother (Michael) can go up one round,’” Benton said of a mob scene unlike any seen for a fight of that magnitude. Benton’s frustration increased until, after the sixth round, he simply walked away, out of the Superdome and into the night.

“It was a zoo,” he would say later. “It was like watching your baby drown. There was nothing you could do about it. I had no more control of the guy. I was useless. All I could do was get the hell out of there.”

The unanimous decision for Ali – by margins of 11-4 and 10-4-1 (twice) in rounds – was a foregone conclusion, and pretty much evident to everyone early on. Ali was back on top, a king re-crowned, and Leon Spinks was generally dismissed as a one-hit wonder that never should have enjoyed even a temporary stay in his sport’s throne room.

“I don’t think Leon Spinks will ever fight again,” a miffed Arum said after the fight. “It’s only my opinion, but I don’t think so. He doesn’t like to fight, he doesn’t like to train. He was drunk about every night down here. I don’t think we’ll ever be able to get him back into a gym.

“He has money and he doesn’t have to go back (to boxing). To tell you the truth, I think down deep he’s glad that he lost that title. He is a simple guy. He doesn’t need the lifestyle of Muhammad Ali. Leon Spinks’ money will last a long time. He doesn’t live like Muhammad Ali.”

Well, Spinks’ career ring earnings – pegged at $5 million, with $3.75 million for the second Ali fight – didn’t last as long as Arum had predicted. Nor did Leon slip away from the fight game, never to be seen or heard from again; he did get another shot at the heavyweight title, losing on a third-round TKO to Larry Holmes on June 12, 1981, and then on a sixth-round stoppage to WBA cruiserweight ruler Dwight Muhammad Qawi on March 22, 1986. His final bout, an eight-round points loss to Fred Houpe on Dec. 4, 1995, left him with a record of 26-17-3, with 14 KO victories and nine defeats inside the distance. The only boxing Hall of Fame in which he is enshrined is Nevada’s. Michael, on the other hand, was 31-1 (21) as a pro, along the way becoming a multimillionaire and first-ballot inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1994.

“I know I could have made Leon upwards of $50 million if he had disciplined himself doing the right thing for four or five years,” said Butch Lewis, who died in 2011.

After his boxing career ended, Leon lingered on the fringes of combat sports. For someone who had outhustled and defeated a legend like Ali, it had to hurt his fans to see him go into a ring with a wrestler named the Mighty Wojo who lifted him up and threw him onto a cold concrete floor. He capitalized on what remained of his celebrity status here and there, including a gig as a greeter at Mike Ditka’s restaurant in Chicago.

“I have no regrets,” Spinks, his voice a bit slurred, said during his time at Ditka’s restaurant. “I had my good times. I won a gold medal. I won the heavyweight title. I reached as high a point in sports as I could.”

And if he had to do it all over again, what changes would he make?

“People pull you here, they pull you there,” he said of his hectic seven-month title reign. “I was not the type who trusted people right away. I was trying to take care of my business and box, too. You can’t do two things at one time. It was my downfall. When I did start to trust people, they took advantage of me. I found myself with a bunch of people around me I didn’t even know. They had me running in the fast lane.”

Leon was able to find some domestic happiness with wife Brenda Glur Spinks, whom he married in Las Vegas on Oct. 9, 2011. She was by his side when he passed away, but because of COVID-19 restrictions only a few close friends and family members – including his son Cory, who won versions of the welterweight and junior middleweight title — were present.

He remained upbeat even as his medical issues worsened. In 2014 he suffered intestinal damage and was hospitalized after swallowing a piece of chicken bone, which led to multiple surgeries. Then, in mid-December of last year, the TMZ gossip site reported he was in a Las Vegas hospital and “reportedly fighting for his life.” The prostate cancer he had been diagnosed with had spread to his bladder, assuring an outcome as certainly negative as his defense against Ali had been. But he fought as he could, for as long as he could, and that is in and of itself a testament to what had once made him special.

Rest in peace, Leon. So many fighters, good ones, have never known the exhilaration of being an Olympic gold medalist, or a heavyweight champion of the world.

A New Orleans native, Bernard Fernandez retired in 2012 after a 43-year career as a newspaper sports writer, the last 28 years with the Philadelphia Daily News. A former five-term president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, Fernandez won the BWAA’s Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism in 1998 and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service in 2015. In December of 2019, Fernandez was accorded the highest honor for a boxing writer when he was named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the Class of 2020. Last year, Fernandez’s anthology, “Championship Rounds,” was released by RKMA Publishing.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers