Book Review

Thomas Hauser is the Pierce Egan of Our Generation

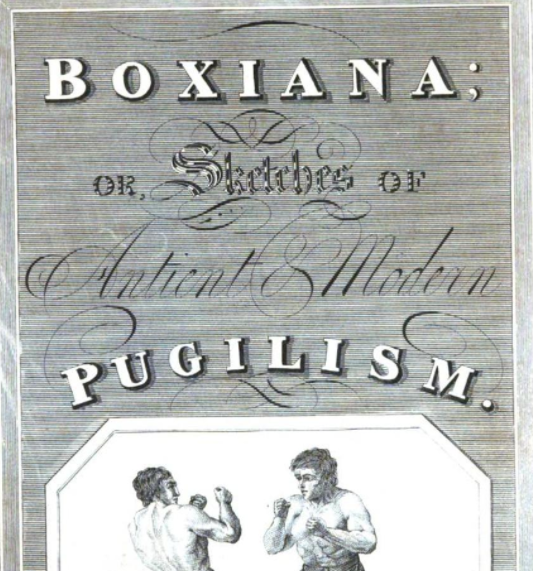

Thomas Hauser is the Pierce Egan of our generation. Two centuries ago, Egan chronicled the goings-on in the world of prizefighting in a series of articles. When he had completed a bunch of these, he knotted them together in a compendium under the title Boxiana; or Sketches of Ancient Pugilism. The first volume was issued in 1813. Four more volumes would follow.

Pierce Egan was drawn to the sport of prizefighting during the so-called Regency Era in England when prizefighting, although an outlaw sport, enjoyed a great burst of popularity. Aristocrats and commoners alike, bluebloods and lowlifes, caravanned to the big fights which of necessity were held outside areas of dense population. But, as indicated by the sub-title of “Boxiana,” Egan was also interested in the history of prizefighting which pre-dated the Regency Era. He wasn’t the first historian of the Sweet Science (a term that he coined), but he was certainly the most influential. Nearly 200 years after his death, a fellow interested in learning about the roots of modern prizefighting is encouraged to start by dredging up a reprint of “Boxiana.” (Or, if one doesn’t wish to be that immersive, checking out one of several collections by the great New Yorker essayist A.J. Liebling who rucked Egan out of obscurity.)

Which brings us to Thomas Hauser.

In common with Pierce Egan, Hauser gathers previously published articles about boxing into a book. A Hauser compendium has become an annual tradition at his publishing house, the University of Arkansas Press. Hauser’s latest offering, the 15th in the series, is fresh off the press. It bears the title Broken Dreams: Another Year Inside Boxing. TSS readers will recognize some of the nuggets as they first appeared at this web site.

Two hundred years from today, if mankind still exists, folks interested in the goings-on in the world of boxing during the first decades of the 21st century, will be directed to the writings of Thomas Hauser. And I have no doubt that a complete set of his annual anthologies, although released in paperback, will be a prized collectable.

Pierce Egan did round-by-round reports of major fights, but he was more interested in things that happened outside the ring. He saw the big picture; prizefighting as an ecosystem. Hauser likewise views the sport through a wide lens. The power brokers command his attention, as do those on the periphery. Hauser once wrote a story about ring card girls that was a fun read and would have also fit neatly as an insert in a textbook on the sociology of work.

“The boxing scene,” wrote Hauser, “is about so much more than the fights.”

In his role as an investigative reporter, for which he has won several awards, Hauser has written extensively about PED abuse in boxing and about the failings of the New York State Athletic Commission.

There’s less about PEDs in his newest book than in previous editions, inevitable perhaps considering that boxing activity in 2020 was stunted by the pandemic, but the NYSAC gets its usual comeuppance. The agency “has long been a favor bank for powerful economic interests and a source of employment at various levels for the politically well connected,” says Hauser, who informs us that for several higher-up employees, and one woman in particular, the job there is basically a sinecure and a good paying one at that.

Another recurrent theme in Hauser’s writings is boxing’s waning popularity among America’s youth and what can be done about it. In a story titled “Why Doesn’t Boxing Attract More Young Fans?” Hauser lists 11 reasons why it doesn’t, each of which can be reconfigured into a prong to be used in a campaign to stanch the erosion and reverse the trend.

None of Hauser’s compendiums would be complete without book reviews. Several years ago, Hauser wrote that “the written history of Muhammad Ali is an ongoing construction” and, in 2020, new construction continued at a brisk pace; there was a spate of new Ali books.

Hauser, needless to say, is well-versed in the subject matter. He interviewed more than 150 people for his 1991 book, “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” long considered the definitive Ali biography, and he takes a fine-tooth comb to any book that traverses the same territory. Factual inaccuracies gall him and he doesn’t hesitate to point them out in reviews of books concerning Ali by Todd Snyder, Stuart Cosgrove, and Rahaman Ali (Muhammad Ali’s brother) and in a book for young readers ostensibly co-authored by book-seller extraordinaire James Patterson.

“Broken Dreams” is divided into four sections, the last of which is titled “Boxing and the Coronavirus.” There are some stories in this section that I suspect wouldn’t make the cut if Hauser were assembling the book today. He writes that “the restoration of normalcy (in boxing) will be a long, slow process.” With the benefit of hindsight, the future wasn’t quite so gloomy.

Among my favorite stories in Hauser’s newest compilation, which clocks in at 308 pages, is a long piece about Gleason’s Gym which, like Madison Square Garden, is currently in its fourth location. There are 44 components in all, modules of various length, and it’s the sort of book that one can open to any page and find something interesting.

—

Notes

Thomas Hauser and Pierce Egan have other things in common aside from their association with prizefighting. Both wrote about other things. Egan, who died in 1849, achieved his greatest success with a work of fiction, Life in London, about the escapades of Corinthian Tom and his country cousin Jerry, excitement-seekers who flouted the norms of society as they caroused about the London metropolis. The book gave rise to a long-running play, to a popular 18th-century expression (“Tom and Jerrying” denoted a rowdy night on the town), to a once-popular Christmas cocktail, and to a cat and mouse team in a children’s animated cartoon series.

In his review of Hauser’s Ali biography, Dave Anderson of the New York Times noted that this was Hauser’s 14th book and that seven of his previous books were novels. Among the non-fiction books that Hauser authored prior to “Ali” was “The Execution of Charles Horman” about the murder of an American journalist who disappeared in Chile during a right-wing military coup. It was adapted into the Oscar-winning screenplay for the movie “Missing” starring Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek.

Lastly, a caveat: Although A.J. Liebling thought Pierce Egan was a real hoot, the average reader will likely find Boxiana hard to digest. The book is freighted with slang terms, some of Egan’s invention, that long ago disappeared from the lexicon.

Egan eventually turned away from boxing cold-turkey, purportedly disgusted by too many fixed fights. If Hauser follows his example, let’s hope that it doesn’t happen any time soon.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers