Featured Articles

The Dempsey-Gibbons Fiasco: An Odd Duck in Boxing’s Rollicking Summer of ‘23

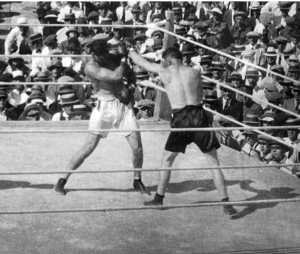

This coming Fourth of July marks the 100th anniversary of one of the oddest promotions in boxing history, the heavyweight championship fight between Jack Dempsey and Tommy Gibbons in remote Shelby, Montana. TSS special correspondent Rich Blake, an authority on prizefighting during the so-called Golden Age of Sports, looks back at that bizarre event.

Around midnight one evening in mid-May of 1923, the 20th Century Limited, crown jewel of American passenger rail travel, came streaking through central New York’s Mohawk Valley en route to Chicago.

Riding in a luxury Pullman car was Jack “Doc” Kearns, a focal point of the sporting world as he attempted to pull off one of the most outlandish sporting schemes ever conceived. A raconteur in a flashy suit, Kearns was the manager of Jack Dempsey, the world heavyweight champion. Throughout that night, the 40-year-old Kearns played cards with scoop-hungry scribes and an old friend, Benny Leonard, then reigning lightweight champion.

Before climbing aboard, Kearns reportedly had arranged for one final meeting with the fight game’s foremost promoter, George “Tex” Rickard, who not only ran Madison Square Garden but also had wangled permission to stage outdoor bouts that summer at the newly opened, 58,000-seat Yankee Stadium.

Garrulous, manipulative, Kearns was sticking it to Rickard by way of an ambitious plot to circumvent the boxing world’s Mecca. Kearns had arranged to stage Dempsey’s next fight – a July 4th championship extravaganza against Tommy Gibbons – in the middle of nowhere. A 34-year-old light heavyweight from the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, Gibbons was known for his speed and clever tactics.

Rickard didn’t flinch. At age 53, the former gold prospector and casino operator was under siege by headline writers, not to mention state boxing authorities, over a string of sensational scandals, including ticket gouging allegations.

Nevertheless, Rickard was quietly reasserting control over the lease on the Garden (the property was owned by the New York Life Insurance Company) and holding sway over issues such as who should challenge Dempsey for the title, where would that fight be held, and how much the least expensive tickets would cost?

Kearns connivingly outmuscled Rickard (and his hefty cut of the gate) earlier that spring by striking a deal with a group of Shelby, Montana, oil field operators reimagining their cowpoke settlement near the Canadian border as the host of a world-class sporting event.

Kearns insisted on a $300,000 payday, extracting one-third of it up front. Shelby’s residents tapped all possible resources to get the money together and started scrambling to build a giant wooden stadium. All the while, Kearns was still playing the angles.

So, was Rickard willing to match the Shelby offer?

“I wouldn’t pay a nickel to see Tommy Gibbons,” Rickard reportedly said, turning Kearns down.

What eventually played out in remote northwest Montana in that rollicking summer of ’23 remains the stuff of cultural lore, a glorious fiasco that is still talked- about one century later.

***

The decade that roared, as of the midpoint of 1923, was not yet in full-throated form, at least in terms of sheer, unbridled jazz-and-hooch-infused zeitgeist energy.

Dempsey’s exploits dominated headlines. But boxing was teeming with colorful characters and contenders. Talented fighters in every weight class made a living competing in rings found in virtually every city in every state.

To rediscover this specific, fascinating slice of a so-called “golden age” is both an intoxicating thrill-ride and a sobering wake-up call. Boxing dominated society as it never had before, and reflected it, for better and for worse.

An endlessly rich tapestry of pugilistic storylines filled the pages of magazines such as The Police Gazette, The Ring and The Boxing Blade. Two dozen or more sportswriters were on the beat – just in New York City, where every neighborhood had its champion. It was a flag of ethnic pride, as Jack Newfield once explained to PBS. “Rivalries were built on ethnic tension,” he said. “You could get ten thousand people for a fight between two neighborhood heroes.”

Boxing flourished almost everywhere. In New York City, each of the five boroughs had multiple boxing clubs. A regional city, such as Buffalo, N.Y., supported two major boxing events per week at the 10,000-seat Broadway Auditorium. Fighters could earn a decent living in the middle-tier markets all while hoping to catch the attention of some manager or matchmaker in the Big Town. A Boxing Blade issue from around this time chronicled a week’s worth of noteworthy fights in New York and Boston, Detroit and Philadelphia, Buffalo and Milwaukee, as well as in Erie, Pa., Sandusky, Ohio, Newark, N.J., Staten Island, N.Y., Flint, Mich., Wichita, Kan., Springfield, Ill. and Cedar Rapids, Iowa, just to list a small sample of locales during one seven-day stretch.

Summertime, the outdoor season – that’s when the brightest stars came out to shine. Fights were staged at ballparks, velodromes and seaside resorts.

After boxing in New York was re-legalized under the liberal Walker Law in 1920, it exploded into a full-fledged industry with its informal headquarters at Madison Square Garden, operated by Rickard. The bulk of his public relations wound up essentially outsourced to a murderers row of syndicated sportswriters – Damon Runyon and Grantland Rice, to name two of the most iconic.

Stephen Dubner, co-author of the popular “Freakonomics” book series, unearthed research by the American Society of Newspaper Editors that showed one out of four readers bought a paper for the sports page. The editors voted Dempsey the “greatest stimulation to circulation in twenty years.”

***

Of course, no retrospective on boxing circa the summer of ’23 can sidestep a fight that should have been – but never was.

Dempsey always insisted he was open to taking on black opponents. The leading heavyweight challenger heading into that summer of ’23 was 34-year-old Harry Wills, dubbed the world’s “colored” heavyweight champion. As such, Wills proved a reliable draw among white audiences, provided he took on a black challenger.

Wills was a burly ex-dockworker from New Orleans, transplanted from the Big Easy to the Big Apple. He was growing old waiting for authorities to force Dempsey to accept his challenge. Frustrated, his career going in circles (he fought Sam Langford at least 17 times), Wills would eventually align himself with a couple of Irishmen. He sought out a new manager, Paddy Mullins, a Bowery bar owner who grew up staging backroom fights, and who was old friends with a Queens promoter named Simon Flaherty who was keen to build a stadium suitable for putting on Dempsey-Wills.

The stadium, situated across from Manhattan in Long Island City, got built, got shut down by the fire department, was refurbished and then re-opened. But Wills’ title shot never happened.

Historians have blamed public sentiment alongside powerful figures such as Rickard (who once supposedly, infamously, told one financial backer the title would be worthless if a black man ever won it) and William Muldoon, the head of the New York Boxing Commission, an avowed opponent of interracial matches in his younger days.

(In Edward Van Every’s biography of Muldoon, “The Solid Man of Sport,” there’s a reference — repeated in Roger Kahn’s biography of Dempsey, “A Flame of Pure Fire” — to a Dempsey-Wills championship match supposedly, at least momentarily, having been made by Rickard who penciled in the Polo Grounds, a sporting coliseum near Yankee Stadium, as a possible location. But the white establishment of 1923 so loathed the thought of a black champion that the idea was quashed. And while the Muldoon-led boxing governing body at one point publicly demanded Dempsey sign papers to fight Wills or forfeit his crown — curiously flouting formal and informal rules forbidding mixed-race bouts — there were also reports that, concurrently, behind the scenes, Albany politicians pressured Muldoon and Rickard to scrap the idea.)

Additionally, Montreal was also considered as a location until, per Van Every, Her Majesty’s government quietly intervened.

Wills had defended what sports pages called his colored heavyweight championship in the fall of ’22 against Clem Johnson at Madison Square Garden (then located on Twenty-Second Street). Wills knocked him out in front of 10,000 fans. Sportswriters were divided on the top contender’s performance. “The giant New Orleans black challenger for the world’s heavyweight boxing title, held by Jack Dempsey, last night battered his way to victory,” the New York Times said.

“That dismal exhibition put up by Harry Wills against Clem Johnson in the Garden may have been the one thing needed to make a Dempsey-Wills bout possible,” the New York Sun said. “Jack Kearns has been telling the boys that Wills has gone back so far that he is not one-fourth as good as he was a few years ago.”

Kearns may have been right, the newspaper added. “But it is possible that he does not pay as much attention to the fact that Wills did not train very seriously for the Johnson affair. With two or three months of real training under his belt, Harry may prove to be a different sort of a fighter.”

So, sportswriters of the day wanted to see Dempsey-Wills and treated “The Black Panther” as a legitimate challenger, stoking curiosity in a bout supposedly the public did not want to see.

As Boxing Scene once put it, citing historian Kevin Smith, Wills’ primary asset was his strength.

“He could move other men around the ring as he pleased,” Smith said.

Considered a top contender for almost seven years, Wills never could fathom or accept being denied a title shot.

“No number one contender could be ignored for that long today,” Smith said. “But the racial tones of that time simply would not allow such a bout.”

Kahn would write that with Rickard, “the issue was money, not prejudice. Or, anyway, money before prejudice.”

***

The scuttling of the Dempsey-Wills match, were it ever really in the cards to begin with, opened the door to a curious chain of events that led to one of the craziest boxing tales of all time.

Loy J. Molumby, an ex-fighter pilot and the cowboy-boots-wearing head of Montana’s American Legion, tracked down Dempsey’s manager in a New York hotel, after being stood-up in Chicago. Molumby carried with him a satchel filled with $100,000. It was the one-third (of the total guaranteed $300,000) that Kearns had demanded up front before he would even discuss such a preposterous concept.

Shelby’s residents tapped all possible resources to get the money together and started scrambling to make arrangements. Roads needed paving. The little railroad depot needed to be expanded. A local lumberyard sprang for $80,000 worth of pine boards for the hasty construction of an open-air octagon.

In 1923, Shelby was a community with “visions – delusions, as it turned out – of boom-town grandeur,” said Jeff Welsch, a Montana sportswriter. Three years earlier, according to the decadal census, fewer than 600 people lived there.

Did we mention there were no paved roads?

An oil strike on a nearby ranch the previous year sparked fantasies of Shelby as the “Tulsa of the West,” according to Welsch.

After giving Rickard a chance to match the Shelby offer, Kearns headed off to rendezvous with Dempsey who was doing some fly fishing on the Missouri River.

The plan was to meet at a training camp being established on the grounds of an old roadhouse on the outskirts of Great Falls, Montana, some 90 miles south of the proposed site of the Independence Day spectacle. The Dempsey faction – Jack’s brother, Johnny, the trainers, and a bull terrier mascot – were preparing the camp. Meanwhile, Kearns put together a deep stable of sparring partners, 17 and counting. Kearns wanted speedy fighters to get the champ prepared for Gibbons, known for being fast with his punches, but Kearns was also widening his talent stable. Red Carr, manager of then-19-year-old Jimmy Slattery, a future light heavyweight champion, would be enticed by an offer from Kearns to send his then-ripening speed boy out to Great Falls, but Red, after giving his blessing, reversed course and nixed the idea.

As for the July 4th heavyweight championship fight staged in the tiny town of Shelby, Montana, it would rank among the most monumental fiascos in the history of sports.

Molumby paid up the second $100,000 installment two months before the fight.

With a week to go, the mayor of Shelby visited Kearns in Great Falls. They only had $1,600 of the final payment. Might he consider accepting 50,000 sheep instead of hard cash?

Dempsey, listless in training, beat, but never dominated Gibbons in a tedious affair witnessed by fewer than 20,000 spectators, half of whom crashed the gates.

The temperature at ringside was close to 100 degrees.

The big takeaway: Dempsey, two years idle from ring activities, failed to knock Gibbons out.

Dempsey and Kearns, along with an armed security detail, fled the scene as fast as they could by private train.

Kearns got out of town with the gate receipts. The banks of Shelby, which had underwritten the event, went bankrupt.

As for Tommy Gibbons, who wound up with nothing, he went on to become the long-serving sheriff of Minnesota’s Ramsey County, home to the State Capitol of St. Paul. As for Dempsey, he would soon journey back east to begin training for his next opponent Luis Angel Firpo, but that’s a story for another day.

Editor’s postscript: The population of Shelby is now a shade over 3,000. The locals no longer consider the fight a civic embarrassment, but rather as something to commemorate. This year, the July 4 festivities will be wrapped around the centennial of Shelby’s “Fight of the Century.” Months of planning have gone into making this Shelby’s grandest Fourth of July ever. Contact the Shelby Area Chamber of Commerce (406-434-7184) for more information.

Rich Blake is a journalist and the author of four non-fiction books, including 2015’s “Slats: The Legend & Life of Jimmy Slattery.”

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds