Featured Articles

Shadow Boxing at the Golden Gate, Part 2

“Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.”

—Henry David Thoreau

“Redcap” Eddie’s blitz began under a shadow of concern, particularly Eddie Muller’s. The writer openly wondered about his “long layoff” and thus underlined the difference between fighters then and fighters now: the lag time since Booker’s last bout was only seven months.

“Booker isn’t picking a soft one,” wrote Muller. Harry “Kid” Matthews had not been stopped in forty-three bouts and had a left hook that was turning all kinds of heads. It looked like a classic boxer versus puncher match-up with Booker as the boxer. Muller, who understood that a fighter with compromised vision had to make adjustments, saw things differently. He wrote that Booker will “do more punching than boxing” and will “make Matthews hustle at close quarters” and that is precisely what happened. Booker tore into his young opponent and smothered anything he tried to do while winging punches to the flank. When two short rights landed to his chin in the second round, Booker just “shook ‘em off” and soon landed a right uppercut that saw Matthews’ knees sag. The match was stopped in the fifth round.

After that beating, Matthews sought less violent settings and enlisted in the U.S. Army. He resumed his career in 1946 and won his next fifty-two fights.

Booker first met Holman Williams at Madison Square Garden in 1939 on the Joe Louis-John Henry Lewis undercard.The first of what would be three studies in skill and violence ended in a draw. Williams, a 2008 International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee and Eddie Futch’s pick as “the greatest pure boxer” he had ever worked with, was matched skill-for-skill and punch-for-punch.

The second time they met was four years later. Thanks to Muller, we know what happened. Williams was on wheels, a “hit-and-run artist” operating behind an educated jab while Booker practiced the dark arts of body-snatching. Booker was storming in while William’s jab and superior speed neutralized his attack. In the eighth and ninth, he was even making him miss wildly and outslugging him at close quarters. In the tenth, Booker shoveled in a right uppercut, hurt him and pinned him on the ropes. The fight was even. In the last round, both answered the bell with war-hats though Williams’ light artillery—the jab—reasserted itself to earn the judges’ nod.

Booker privately blamed the loss on sweating weight off shortly before the bout. Within two months he stepped into the ring at a comfortable 170 lbs against a heavyweight. Booker floored him twice before the referee spared his ribs by stopping the fight.

The Mongoose was next in line. The day after they fought to a draw in 1941, Archie Moore was raking leaves in his front yard when he suddenly felt like a “red-hot iron” had been thrust into his stomach. As he was lying there on the grass blaming Booker’s body shots, his aunt called an ambulance. “I was sure that I was dying,” he recalled. Doctors told him that he had suffered a perforated ulcer and emergency surgery was required to save his life. After eleven months he recovered, returned to the ring, and signed to face his nemesis again. With a license plate stuck inside the waistband of his no-foul protector, Archie barreled after Booker in the rematch, put him down—and barely got by with another draw.

After two contests, neither could claim superiority over the other. Booker later said that he knew how tough Moore was and informed his manager that he was in no hurry to meet him a third time. Moore wasn’t eager either, though back then reluctance wasn’t so synonymous with avoidance. Their third and final battle was scheduled for January 21st 1944.

Muller’s favorite fighter prepared himself by sparring with Pat Valentino, a San Francisco heavyweight. Muller was in the gym. Neither “held anything back,” he wrote, “and as a result, Booker was able to whip himself into tip top shape.”

The first four rounds of Booker-Moore III saw both men fighting on even terms as they sketched their strategic outlines with short punches inside. The crowd, art lovers none, was booing. Then Booker hit Moore with his easel. He landed a left hook in the fifth and down went Moore like a drop cover, barely beating the count when the round ended. The sixth and seventh rounds saw the Mongoose saved by the bell twice more. In the eighth, another left hook sent him down with plenty of time left in the round. Seconds later, Moore was sinking in slow motion when the referee thrust Booker’s hand in the air.

It was among the most decisive defeats of Moore’s long career; the first time he was stopped in over sixty bouts, and he was in his self-declared prime.

The victory prompted an Oakland promoter to try to sign Booker and Charley Burley for February 22nd or 23rd. It fell through. Booker may have welcomed a chance to avenge himself against Jack Chase, but the prognosis on his eye was getting steadily worse and there was unfinished business with Holman Williams.

The result of Booker-Williams III would either even up the score or see Williams win the series. Besides defeating Booker, Williams had also dominated Booker’s conqueror in Chase twice the previous month. The Chicagoan was installed as a 2-1 favorite, but Muller knew that Booker’s time was running out and smelled an upset. He knew the fury born of desperation.

As the fighters met in the middle of the ring at the Civic Auditorium, Williams immediately tried to re-establish that “snake like jab,” only this time, Booker was slipping it and ripping shots to the body. For the next three rounds Muller saw his man “charging in and banging away with lefts and rights” to the midsection; and in the third the crowd jumped to its feet when he smashed Williams with two rights to the jaw. Williams was forced to exchange and although he was outlanding the relentless body-snatcher and outsmarting him in close and at range, it was Booker’s guns that carried more force. The tenth could have been a candidate for “Round of the Year” as both “slugged it out for three full minutes without let-up.”

Muller’s penchant for suggesting strategy and then seeing his suggestions confirmed in the performance were on display. He insisted before the bout that Booker’s extra poundage will help if he “puts it to good use” and gets rough inside without getting careless. “Eddie must give his all,” Muller predicted, “he can’t afford to loaf at any time.” Eddie paid attention.

As his hand was raised at the final bell, the applause shook the rafters.

The war that was Booker-Williams III was talked about for days afterward around the Bay Area. Muller gave it a considerable amount of press and believed that the victory would place Booker in a position to demand a shot against Jake LaMotta if he came to San Francisco. The fight took in $11,972.15, which was good enough for a non-white main event to encourage the promoter to consider a fourth bout for early April.

April turned out to be a busy month for Murderers’ Row. LaMotta never did come west—so the Row went looking for him: On April 21st, hard-punching Lloyd Marshall, whom Booker had beaten so impressively, took a unanimous decision over the Bronx Bull in Cleveland. On the same day, Burley humiliated Moore almost as badly as Booker did in Hollywood. Chase lost to Burley on April 6th and three weeks later went the last seven rounds against Williams with a dislocated jaw and lost better.

Booker, twenty-seven and almost half-blind, was the odd man out. An ophthalmoscope saw that his gloves were hung on a hook.

Rated by The Ring in the welterweight, middleweight, and light heavyweight divisions from April 1939 through June 1944, he ascended to a career-high number two in the world after his last bout and finished with a record of 66-5-8. Fighters campaigning up and down the West Coast breathed easier when he retired. Burley, with five bouts at the auditorium under his belt, narrowly missed a collision with him and was lucky for it. He told a mutual sparring partner that Booker would have been his “hardest fight.”

He was right. Booker’s fateful decision to resume his career despite the risks unveiled a level of craft and character rarely seen. The golden blitz—those last frenzied fights over a seven-month stretch—were finishing touches to a monument that stood in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge.

It stands there still, under the dust of seven decades.

It stands despite the silence of seven decades.

Like travelers at the railroad station who barely noticed the redcap carrying their bags, who never saw the danger in those gnarled knuckles or the glint in that dying eye, the sport of boxing has failed to recognize Eddie Booker. Not long after his retirement, A.J. Liebling mentioned him as an opponent of Archie Moore who “left no footprints on the sands of time.” The Baltimore African American thought he was white.

Booker shrugged his shoulders and moved on, though not very far. He took time to train local amateurs who followed him through Golden Gloves tournaments and became a licensed corner man in the Bay Area. For twenty years he was the polite and unassuming clerk at Post Hardware on Sutter Street. The store was on the same street as his home and only a short walk from the Civic Auditorium.

Eddie Muller, our invaluable eyewitness for so many of his bouts, stayed close too. The San Francisco Examiner was located at the intersection of 3rd, Kearney, and Market, just a few blocks south of Sutter. Known as “Mr. Boxing,” Muller covered nothing but the Sweet Science in his column “Shadow Boxing.” It ran for forty-four years. He bore black and white witness to the quiet man’s wars, aged with him, and remembered him at the end.

Thirty years after his last great victory over a third Hall of Famer, Booker’s heart stopped and Muller—still there for him and for us—wrote his obituary.

It was fitting.

__________________

It is the strong opinion of this writer that both Eddie Booker and Eddie Muller are overdue for induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Details about Booker found among the papers of Hank Kaplan. Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Archive is located at the Brooklyn College Library. Special thanks to Harry Otty, Jahongir Usmanov of the Brooklyn College Archives, and Eddie Muller II, the illustrious son of “Mr. Boxing” and the author of two widely-acclaimed noir novels in The Distance and Shadow Boxer —both of which conjure the spirit and the times of Muller and Booker.

Springs Toledo can be contacted at scalinatella@hotmail.com.

Featured Articles

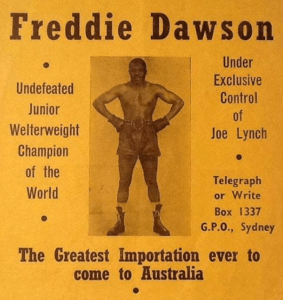

History has Shortchanged Freddie Dawson, One of the Best Boxers of his Era

This reporter was rummaging around the internet last week when he stumbled on a story in the May 1950 issue of Ebony under the byline of Mike Jacobs. Boxing was then in the doldrums (isn’t it always?) and Jacobs, the most powerful promoter in boxing during the era of Joe Louis, was lassoed by the editors of the magazine to address the question of whether the over-representation of black boxers was killing the sport at the box office.

This hoary allegation had been kicking around even before the heyday of Jack Johnson, bubbling forth whenever an important black-on-black fight played to a sea of empty seats as had happened the previous year when Chicago’s Comiskey Park hosted the world heavyweight title fight between Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott.

Jacobs ridiculed the hypothesis – as one could have expected considering the publication in which the story ran – and singled out three “colored” boxers as the best of the current crop of active pugilists: Sugar Ray Robinson, Ike Williams, and Freddie Dawson.

Sugar Ray Robinson? A no-brainer. Skill-wise the greatest of the great. Even those that didn’t follow boxing, would have recognized his name. Ike Williams? Nowhere near as well-known as Robinson, but he was then the reigning lightweight champion, a man destined to go into the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the inaugural class of 1990.

And Freddie Dawson? If the name doesn’t ring a bell, dear reader, you are not alone. I confess that I too drew a blank. And that triggered a search to learn more about him.

Freddie Dawson had four fights with Ike Williams. All four were staged on Ike’s turf in Philadelphia. Were this not the case, the history books would likely show that the series knotted 2-2. Late in his career, Dawson became greatly admired in Australia. But we are jumping ahead of ourselves.

Dawson was born in 1924 in Thomasville, Arkansas, an unincorporated town in the Arkansas Delta. Likely a descendent of slaves who worked in the cotton plantations, he grew up in the so-called Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago, the heart of Chicago’s Black Belt.

The first mention of him in the newspapers came in 1941 when he won Chicago’s Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) featherweight title. In those days, amateur boxing was big in the Windy City, the birthplace of the Golden Gloves. The Catholic Archdiocese, which ran gyms in every parish, and the Chicago Parks Department, were the major incubators.

In his amateur days, he was known as simply Fred Dawson. As a pro, his name often appeared as Freddy Dawson, although Freddie gradually became the more common spelling.

Dawson, who stood five-foot-six and was often described as stocky, made his pro debut on Feb. 1, 1943, at Marigold Gardens. Before the year was out, he had 16 fights under his belt, all in Chicago and all but two at Marigold. (Currently the site of an interdenominational Christian church, Marigold Gardens, on the city’s north side, was Chicago’s most active boxing and wrestling arena from the mid-1930s through the early-1950s. Joe Louis had three of his early fights there and Tony Zale was a fixture there as he climbed the ladder to the world middleweight title.)

The last of these 16 fights was fatal for Dawson’s opponent who collapsed heading back to his corner after the fight was stopped in the 10th round and died that night at a local hospital from the effects of a brain injury.

Dawson left town after this incident and spent most of the next year in New Orleans where energetic promoter Louis Messina ran twice-weekly shows (Mondays for whites and Fridays for blacks) at the Coliseum, a major stop on boxing’s so-called Chitlin’ Circuit.

That same year, on Sept. 19, 1944, Dawson had his first encounter with Ike Williams. He was winning the fight when Ike knocked him out with a body punch in the fourth round.

The first and last meetings between Dawson and Ike Williams were spaced five years apart. In the interim, Freddie scored his two best wins, stopping Vic Patrick in the twelfth round at Sydney, NSW, and Bernard Docusen in the sixth round in Chicago.

The long-reigning lightweight champion of Australia, Patrick (49-3, 43 KOs) gave the crowd a thrill when he knocked Dawson down for a count of “six” in the penultimate 11th round, but Dawson returned the favor twice in the final stanza, ending the contest with a punch so harsh that the poor Aussie needed five minutes before he was fit to leave the ring and would spend the night in the hospital as a precaution.

Dawson fought Bernard Docusen before 10,000-plus at Chicago Stadium on Feb. 4, 1949. An 8/5 favorite, Docusen lacked a hard punch, but the New Orleans cutie had suffered only three losses in 66 fights, had never been stopped, and had extended Sugar Ray Robinson the 15-round distance the previous year.

Dawson dismantled him. Docusen managed to get back on his feet after Dawson knocked him down in the sixth, but he was in no condition to continue and the referee waived the fight off. Dawson was then vacillating between the lightweight and welterweight divisions and reporters wondered whether it would be Robinson or Ike Williams when Dawson finally got his well-earned title shot.

Sugar Ray wasn’t in his future. Here are the results of his other matches with Ike Williams:

Dawson-Williams II (Jan. 28, 1946) – The consensus on press row was 7-2-1 or 7-3 for Dawson, but the match was ruled a draw. “[The judges and referee] evidently saw [Williams] land punches that nobody else did,” said the ringside reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Dawson-Williams III (Jan. 26, 1948) – Dawson lost a majority decision. The scores were 6-4, 5-4-1, and 4-4-2. The decision was booed. Ike Williams then held the lightweight title, but this was a non-title fight. (It was tough for an outsider to get a fair shake in Philadelphia, home to Ike Williams’ co-manager Frank “Blinky” Palermo who would go to prison for his duplicitous dealings as a fight facilitator.)

Dawson-Williams IV (Dec. 5, 1949) – This would be Freddie Dawson’s only crack at a world title and he came up short. Ike Williams retained the belt, winning a unanimous decision. The fight was close – 8-7, 8-7, 9-6 – but there was no controversy.

Dawson made three more trips to Australia before his career was finished. On the first of these trips, he knocked out Jack Hassen, successor to Vic Patrick as the lightweight champion of Australia. A 1953 article in the Sydney Sunday Herald bore witness to the esteem in which Dawson was held by boxing fans in Australia: “None of our boxers could withstand his devastating attacks which not only knocked them out but also knocked years off their careers,” said the author. “It is doubtful whether any Australian boxer in any division could have beaten Dawson.”

Dawson had his final fights in the Land Down Under, finishing his career with a record of 103-14-4 while answering the bell for 962 rounds. Following what became his final fight, he had an eye operation in Sydney that was reportedly so intricate that it required a two-week hospital stay. He injured the eye again in Manila while sparring in preparation for a match with the welterweight champion of the Philippines, a match that had to be aborted because of the injury. Dawson then disappeared, by which we mean that he disappeared from the pages of the newspaper archives that allow us to construct these kinds of stories.

What about Freddie Dawson the man? A 1944 story about him said he was an outstanding all-around athlete, “a champion in all athletic undertakings – basketball, baseball, track and even jitterbugging.” A story in a Sydney paper as he was preparing to meet Vic Patrick informs us that he had two young children, ages 2 and 1, owned his own home in Chicago, and drove a two-year-old Cadillac. But beyond these flimsy snippets, Dawson the man remains elusive.

What we learned, however, is that he was one of the most underrated boxers to come down the pike in any era, a borderline Hall of Famer who ought not have fallen through the cracks. Inside the ring, this guy was one tough hombre.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

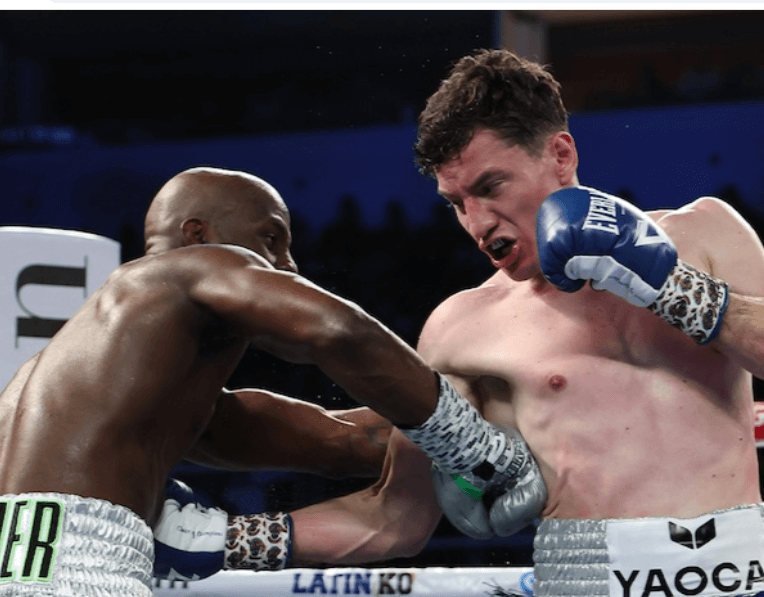

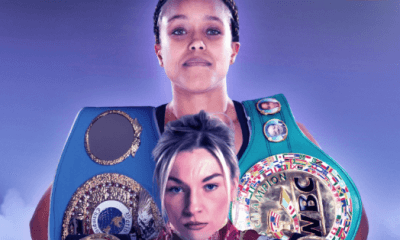

Ringside at the Fontainebleau where Mikaela Mayer Won her Rematch with Sandy Ryan

LAS VEGAS, NV — The first meeting between Mikaela Mayer and Sandy Ryan last September at Madison Square Garden was punctuated with drama before the first punch was thrown. When the smoke cleared, Mayer had become a world-title-holder in a second weight class, taking away Ryan’s WBO welterweight belt via a majority decision in a fan-friendly fight.

The rematch tonight at the Fontainebleau in Las Vegas was another fan-friendly fight. There were furious exchanges in several rounds and the crowd awarded both gladiators a standing ovation at the finish.

Mayer dominated the first half of the fight and held on to win by a unanimous decision. But Sandy Ryan came on strong beginning in round seven, and although Mayer was the deserving winner, the scores favoring her (98-92 and 97-93 twice) fail to reflect the competitiveness of the match-up. This is the best rivalry in women’s boxing aside from Taylor-Serrano.

Mayer, 34, improved to 21-2 (5). Up next, she hopes, in a unification fight with Lauren Price who outclassed Natasha Jonas earlier this month and currently holds the other meaningful pieces of the 147-pound puzzle. Sandy Ryan, 31, the pride of Derby, England, falls to 7-3-1.

Co-Feature

In his first defense of his WBO world welterweight title (acquired with a brutal knockout of Giovani Santillan after the title was vacated by Terence Crawford), Atlanta’s Brian Norman Jr knocked out Puerto Rico’s Derrieck Cuevas in the third round. A three-punch combination climaxed by a short left hook sent Cuevas staggering into a corner post. He got to his feet before referee Thomas Taylor started the count, but Taylor looked in Cuevas’s eyes and didn’t like what he saw and brought the bout to a halt.

The stoppage, which struck some as premature, came with one second remaining in the third stanza.

A second-generation prizefighter (his father was a fringe contender at super middleweight), the 24-year-old Norman (27-0, 21 KOs) is currently boxing’s youngest male title-holder. It was only the second pro loss for Cuevas (27-2-1) whose lone previous defeat had come early in his career in a 6-rounder he lost by split decision.

Other Bouts

In a career-best performance, 27-year-old Brooklyn featherweight Bruce “Shu Shu” Carrington (15-0, 9 KOs) blasted out Jose Enrique Vivas (23-4) in the third round.

Carrington, who was named the Most Outstanding Boxer at the 2019 U.S. Olympic Trials despite being the lowest-seeded boxer in his weight class, decked Vivas with a right-left combination near the end of the second round. Vivas barely survived the round and was on a short leash when the third stanza began. After 53 seconds of round three, referee Raul Caiz Jr had seen enough and waived it off. Vivas hadn’t previously been stopped.

Cleveland welterweight Tiger Johnson, a Tokyo Olympian, scored a fifth-round stoppage over San Antonio’s Kendo Castaneda. Johnson assumed control in the fourth round and sent Castaneda to his knees twice with body punches in the next frame. The second knockdown terminated the match. The official time was 2:00 of round five.

Johnson advanced to 15-0 (7 KOs). Castenada declined to 21-9.

Las Vegas junior welterweight Emiliano Vargas (13-0, 11 KOs) blasted out Stockton, California’s Giovanni Gonzalez in the second round. Vargas brought the bout to a sudden conclusion with a sweeping left hook that knocked Gonzalez out cold. The end came at the 2:00 minute mark of round two.

Gonzalez brought a 20-7-2 record which was misleading as 18 of his fights were in Tijuana where fights are frequently prearranged. However, he wasn’t afraid to trade with Vargas and paid the price.

Emiliano Vargas, with his matinee idol good looks and his boxing pedigree – he is the son of former U.S. Olympian and two-weight world title-holder “Ferocious” Fernando Vargas – is highly marketable and has the potential to be a cross-over star.

Eighteen-year-old Newark bantamweight Emmanuel “Manny” Chance, one of Top Rank’s newest signees, won his pro debut with a four-round decision over So Cal’s Miguel Guzman. Chance won all four rounds on all three cards, but this was no runaway. He left a lot of room for improvement.

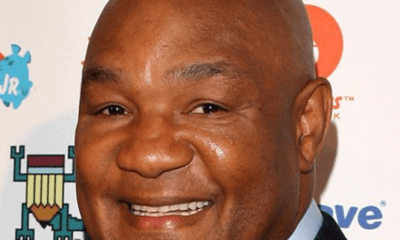

There was a long intermission before the co-main and again before the main event, but the tedium was assuaged by a moving video tribute to George Foreman.

Photos credit: Al Applerose

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

William Zepeda Edges Past Tevin Farmer in Cancun; Improves to 34-0

William Zepeda Edges Past Tevin Farmer in Cancun; Improves to 34-0

No surprise, once again William Zepeda eked out a win over the clever and resilient Tevin Farmer to remain undefeated and retain a regional lightweight title on Saturday.

There were no knockdowns in this rematch.

The Mexican punching machine Zepeda (33-0, 17 KOs) once more sought to overwhelm Farmer (33-8-1, 9 KOs) with a deluge of blows. This rematch by Golden Boy Promotions took place in the famous beach resort area of Cancun, Mexico.

It was a mere four months ago that both first clashed in Saudi Arabia with their vastly difference styles. This time the tropical setting served as the background which suited Zepeda and his lawnmower assaults. The Mexican fans were pleased.

Nothing changed in their second meeting.

Zepeda revved up the body assault and Farmer moved around casually to his right while fending off the Mexican fighter’s attacks. By the fourth round Zepeda was able to cut off Farmer’s escape routes and targeted the body with punishing shots.

The blows came in bunches.

In the fifth round Zepeda blasted away at Farmer who looked frantic for an escape. The body assault continued with the Mexican fighter pouring it on and Farmer seeming to look ready to quit. When the round ended, he waved off his corner’s appeals to stop.

Zepeda continued to dominate the next few rounds and then Farmer began rallying. At first, he cleverly smothered Zepeda’s body attacks and then began moving and hitting sporadically. It forced the Mexican fighter to pause and figure out the strategy.

Farmer, a Philadelphia fighter, showed resiliency especially when it was revealed he had suffered a hand injury.

During the last three rounds Farmer dug down deep and found ways to score and not get hit. It was Boxing 101 and the Philly fighter made it work.

But too many rounds had been put in the bank by Zepeda. Despite the late rally by Farmer one judge saw it 114-114, but two others scored it 116-112 and 115-113 for Zepeda who retains his interim lightweight title and place at the top of the WBC rankings.

“I knew he was a difficult fighter. This time he was even more difficult,” said Zepeda.

Farmer was downtrodden about another loss but realistic about the outcome and starting slow.

“But I dominated the last rounds,” said Farmer.

Zepeda shrugged at the similar outcome as their first encounter.

“I’m glad we both put on a great show,” said Zepeda.

Female Flyweight Battle

Costa Rica’s Yokasta Valle edged past Texas fighter Marlen Esparza to win their showdown at flyweight by split decision after 10 rounds.

Valle moved up two weight divisions to meet Esparza who was slightly above the weight limit. Both showed off their contrasting styles and world class talent.

Esparza, a former unified flyweight world titlist, stayed in the pocket and was largely successful with well-placed jabs and left hooks. She repeatedly caught Valle in-between her flurries.

The current minimumweight world titlist changed tactics and found more success in the second half of the fight. She forced Esparza to make the first moves and that forced changes that benefited her style.

Neither fighter could take over the fight.

After 10 rounds one judge saw Esparza the winner 96-94, but two others saw Valle the winner 97-93 twice.

Will Valle move up and challenge the current undisputed flyweight world champion Gabriela Fundora? That’s the question.

Valle currently holds the WBC minimumweight world title.

Puerto Rico vs Mexico

Oscar Collazo (12-0, 9 KOs), the WBO, WBA minimumweight titlist, knocked out Mexico’s Edwin Cano (13-3-1, 4 KOs) with a flurry of body shots at 1:12 of the fifth round.

Collazo dominated with a relentless body attack the Mexican fighter could not defend. It was the Puerto Rican fighter’s fifth consecutive title defense.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoA Fresh Face on the Boxing Scene, Bryce Mills Faces His Toughest Test on Friday

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBernard Fernandez Reflects on His Special Bond with George Foreman

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoA Paean to George Foreman (1949-2025), Architect of an Amazing Second Act

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNotes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser: Callum Walsh Returns to Madison Square Garden

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFriday Boxing Recaps: Observations on Conlan, Eubank, Bahdi, and David Jimenez

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoSpared Prison by a Lenient Judge, Chordale Booker Pursues a World Boxing Title

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Mikaela Mayer on Jonas vs. Price and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

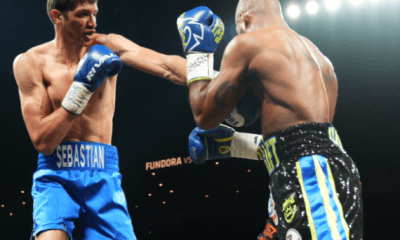

Featured Articles2 weeks agoSebastian Fundora TKOs Chordale Booker in Las Vegas