Featured Articles

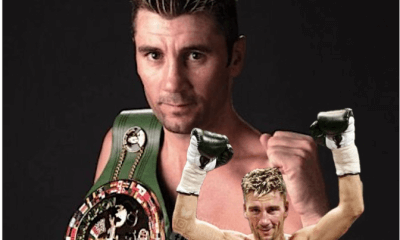

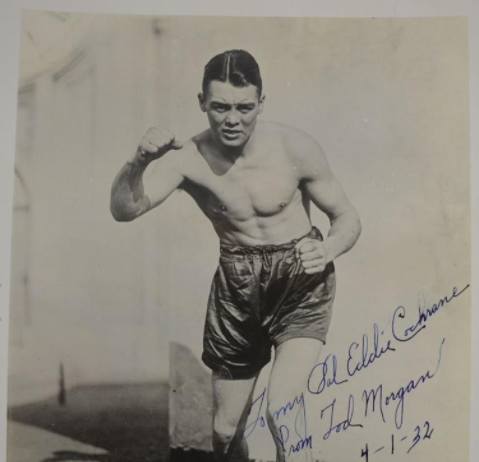

Meet ‘Old-Timer’ Tod Morgan, a New Addition to the Boxing Hall of Fame

On Aug. 3, 1953, Tod Morgan died a pauper in his home state of Washington. He was 50 years old.

After more than 200 pro fights, Morgan had nothing to show for it. A former world junior lightweight champion and the former lightweight champion of Australia, Morgan the ex-boxer worked as a bellman in Seattle hotels until he became incapacitated. But he wouldn’t be completely forgotten. This coming June, nearly 69 years after he drew his last breath, Tod Morgan will be formally inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

The second fighter from the Apple State to be accorded this honor (Tacoma’s Freddie Steele was enshrined in 1999), Morgan was born Albert Pilkington in Sequim, a town on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Taking the surname of his stepfather, Frank Morgan, he made his pro debut at age 17 at a vaudeville house in Concrete, Washington, a town whose major employer was, you guessed it, a cement company.

Morgan was just a few fights into his pro career when he shifted his tack to the town of Vallejo near Oakland on the eastern side of San Francisco Bay. Between October of 1920 and May of 1923, he fought exclusively in California, 50 fights in all. These were all 4-rounders. In November of 1913, the voters in California approved a measure that restricted all fights, amateur and pro, to four rounds. The law remained in effect for 10 years.

After a short stint in Seattle, Morgan returned to California. On Dec. 2, 1925, he made the national news wire when he stopped New Jersey’s Mike Ballerino at LA’s Olympic Auditorium. The match was billed for the world junior lightweight title. Ballerino took all the worst of it until his corner tossed in the towel in the 10th and final round.

His bout with Ballerino would be the first of 15 fights denominated as world title fights in the 130-pound weight class. Morgan’s record in these encounters was 12-2-1.

Six of the title fights were at the Mecca of Boxing, Madison Square Garden.

In his first Madison Square Garden exposure, Martin successfully defended his belt with a lopsided decision over Brooklyn’s Joe Glick. They would fight again in this same ring, a match in which Glick was disqualified for low blows. (The wags would saddle Joe Glick with boxing’s oddest nickname. A tailor by trade, he was dubbed the Brownsville Buttonhole Maker.)

Another Brooklynite, Eddie “Cannonball” Martin, gave Morgan one of his toughest fights when they met at Madison Square Garden on May 24, 1928. The referee and both judges gave the bout to Morgan, but there were dissenters among the ringside press.

Cannonball Martin, who previously had a tenuous hold on the world bantamweight title, was very good, but Morgan left no doubt that he was the better man when they hooked up again. After 15 gory rounds, the decision favoring the West Coast invader was so clear-cut that it was cheered by the pro-Martin crowd. The match was held on a hot and muggy July evening before 20,000 at Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn baseball team that had taken the name Dodgers.

Tod Morgan’s lone setbacks in those 15 title fights came at the hands of Joey Sangor and Benny Bass. Tod didn’t bring his “A” game when he fought Sangor in a 10-round bout at Milwaukee on New Year’s Day, 1929. The newspaper writers were in general agreement that Sangor, a local man, edged it. But Wisconsin was then a no-decision state which meant that Morgan kept his title as it could only change hands in the event of a knockout. His defeat at the hands of Benny Bass at Madison Square Garden on Dec. 20, 1929, was a horse of a different color. The fight had a bad odor about it.

After winning the first round convincingly, Morgan was knocked out in the second. The knockout punch was a clean right hand to the jaw, but the outcome supported the whispers that the fix was in. All of the late money was on Philadelphia’s “Little Fish,” which made no sense as Morgan was far cleverer. In the lobby at Madison Square Garden, the odds favoring Bass soared as high as 6/1.

The New York Athletic Commission withheld the fighters’ purses. They were unable to prove any wrongdoing, but got a measure of satisfaction by abolishing the junior lightweight class – and for good measure, the other junior divisions as well. Other jurisdictions continued to recognize a 130-pound class and New York eventually relented, restoring the weight division in 1949.

Morgan wore out his welcome in the Big Apple with that suspicious performance and would never fight in New York again. He returned to Washington and fought up and down the West Coast before trundling off to Sydney, Australia in the late summer of 1933.

Morgan spent the last nine years of his boxing career in the Land Down Under. He had 62 fights in Australian rings, the vast majority slated for 15 rounds, and promoted a few fights on the side before returning to the United States shortly after the end of World War II.

When he was young, Morgan was known for his fast footwork. “His boxing was a pleasure to the eye,” wrote UPI sports editor Frank Getty, who added that when the occasion warranted, Morgan could out-slug the roughest and toughest. As he grew older, what stood out was his cageyness. “He could punch from any angle or position,” reminisced Sydney southpaw Vic Patrick who won three out of four from Tod Morgan at the tail end of Morgan’s career. “He had a favorite punch that seemed to hit right on the spot, where the liver is, without being an illegal punch.”

Back in the States, Morgan told an Associated Press reporter that he planned to enlist the aid of other Pacific Northwest fighters from his era in the formation of a non-profit “to take care of indigent and/or punchy fighters who have passed their prime.” He had a name for it: the American Professional Boxing Association.

Morgan would need to find a sugar daddy to pull this off as he had virtually no resources of his own. When he left the Antipodes with his Australian wife, he didn’t have the funds to pay his way home for the both of them and hired on as a messman in the ship’s cafeteria.

How can a boxer with that many fights under his belt, and a former long-reigning world champion to boot, leave the sport with only his scrapbook? Keep in mind that the 130-pound division was new and had very little cachet. Also, the last half of Morgan’s career overlapped with the period when most of the world, and especially the U.S. and Australia, were in the grips of the Great Depression. Purses were miniscule.

During Morgan’s day, to steal a line from the great sportswriter Jimmy Cannon, professional prizefighters in the main were paid with what amounted to moving-around-money. It cost money to go places to ply one’s trade, even if one doesn’t go first-class. The expenses — transportation, lodging, meals, etc. — can eat a hole in one’s pocket in a hurry.

In July of 1951, Morgan suffered a stroke while staying in the home of his mother in Reno. Two months later, on Sept. 22, this disheartening item appeared in the Los Angeles Times: “[Tod Morgan] underwent an unsuccessful brain operation in Reno recently…He’s now in a State hospital in his home state of Washington…and without funds.”

According to BoxRec, Morgan finished 133-42-33 with 29 KOs in a career during which he answered the bell for 1664 rounds. When he fell ill, a reporter made this observation: “Tod never turned down an opponent, no matter how tough or famous, and was fighting long years after everyone thought him washed up.”

He’s been dead more years than he lived, but this week he was resuscitated, in a fashion, with the news that he has been named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame. If you happen to visit the Shrine in Canastota, be certain to check his plaque on the wall. It would bring a smile to his face, and he had precious few reasons to smile after he hung up his gloves.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision