Book Review

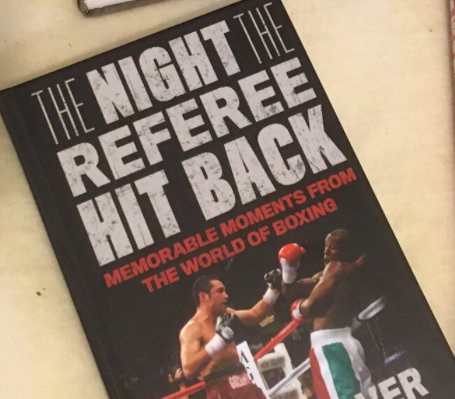

Goodbye To All Of That: A Review of Mike Silver’s ‘The Night the Referee Hit Back’

Goodbye To All Of That: A Review of Mike Silver’s ‘The Night the Referee Hit Back’

Mike Silver has been writing about boxing since the 1970s, which would make him, in the parlance of the youth of today, an “old head,” an appellation that carries wildly contradictory meanings depending on its usage. His 2008 book, The Arc of Boxing: The Rise and Decline of the Sweet Science, was a caustic close reading of how boxing, once a mainstream sport that spoke to the masses, became a small, hemmed-in, navel-gazing affair guided by small men and their equally small thinking.

In this provocative book, Silver excoriated some of the most indubitable pillars in the sport, those whose talents and achievements most fans regard as transcendental, beyond reproach. The reader was hit with one long either/or proposition. Either Silver was “clickbaiting,” engaging in the worst instincts of hot take culture or he was providing a long-overdue corrective, and depending on your frame of mind or allegiances, the answer was stark clear. Here are a couple of snippets from that book:

“Floyd [Mayweather Jr.] continues to win fights without strategizing because his mostly third-rate opponents haven’t a clue as to how to counter his whippet speed. The faux experts praise his ‘technical skill’ because they cannot differentiate between extreme speed and sophisticated boxing technique.”

Of Bernard Hopkins, he writes, “Reviewing tapes of his fights reveals to the knowing eye that Hopkins is an intelligent yet unremarkable boxer possessing decent defensive skills, a professional attitude and a solid punch. While these qualities are more than enough to make him a dominant world champion today, fifty years ago such skills would have been considered commonplace.”

There are those, no doubt, who feel that any criticism leveled at Mayweather or Hopkins, as well as Pernell Whitaker or Roy Jones Jr., are grounds for immediate excommunication. But discount Silver at your own peril. You may not agree with everything that he says, but his observations are a net win for a boxing culture that seems to run more and more on a perpetual feed-back loop of self-regarding hype.

In his new collection of essays, The Night the Referee Hit Back, culled from 40 years of material, Silver has somewhat tempered his venom, eschewing the combative stance of Arc for a more celebratory one. But his opinions have not changed. “My observations are based on my particular frame of reference and perspective,” Silver writes. “To me, the glory and romance of boxing resides in its past history and I’m content to leave it at that.” As Joe Pesci said in The Irishman, “It’s what it is.”

The Night opens up, appropriately, to a bygone vision of New York City when booze still flowed liberally through Toots Shor’s, Jack Dempsey held court at his eponymous watering hole, and boxing “was still an important part of American popular culture.” The nerve center of the city’s prizefighting ecosystem was on 8th Avenue, not at Madison Square Garden, but at nearby Stillman’s Gym, the sweat-caked fighting coop that A.J. Liebling affectionately immortalized as the University on 8th Avenue. The gym, seemingly one of the last connections to Damon Runyon’s New York, shuttered in the early 1960s and has left behind virtually zero trace; no distinguishing vestige, no commemorative plaque. In its place today, within the hellscape of an increasingly corporatized Manhattan, stands a sad pocket of residential real estate surrounded by fast-food chains and a TD Bank.

A young, 14-year-old Silver had the good fortune of being introduced to this private world before it was all razed down two years later. Back then, Silver reminds the reader, “Even an ordinary preliminary boxer could make more money in one four-round bout than a sweatshop laborer made for an entire week.” His reminiscences are offered with a light touch, without falling into a maudlin trap. As Silver describes what it was like walking up the wooden staircase and passing through the turnstile and chatting it up with Kid Norfolk, the reader can almost smell the thick waft of cigar smoke that hung over the gym in those days.

“Dick Tiger, Gaspar Ortega, Emile Griffith, Jorge Fernandez, Joey Archer, Rory Calhoun, Alex Miteff, Ike Chestnut, and others,” Silver recalled, rattling off the fighters he brushed shoulders with on a daily basis. “Is there any other professional sport where a fan can get so close to its star? This was the magic and allure of Stillman’s, and I thank my lucky stars I was able to experience it.”

But the nostalgic anecdotes are kept to a minimum. Most of The Night features pieces that reflect Silver’ analytical nature. “Don’t Blame Ruby,” one of his most insightful pieces, hones in on the infamous 1962 Benny Paret-Emile Griffith welterweight bout in which Griffith ended up sending a comatose Paret to the hospital – and 10 days later, to the grave. Here Silver takes issue with the long-parroted line of thinking that blames the referee of that bout, Ruby Goldstein, for taking too long to wave off the bout. Actually, Silver argues, the truth was much more complicated. Citing Paret’s hellacious fighting schedule – which included an engagement with the deadly Gene Fullmer before his star-crossed meeting with Griffith — Silver points the finger at Paret’s handlers and the bureaucrats who were presumably in charge of overseeing the fighter’s safety. If any blame can be ascribed to an individual or entity, it is them.

In another piece, Silver deconstructs, step-by-step, round-by-round, the mythology behind the snazzily dubbed “The Thrilla in Manila,” the third and final fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier that is often cited as one of the greatest fights in boxing history. Balderdash, says Silver. Anyone who has seen the fight can attest to Silver’s common sense, but that has not stopped the bout from being breathlessly heralded routinely by magazines like The Ring and cable networks like ESPN, which proves the point about boxing being one vast echo chamber. These two pieces alone should quiet those who think Silver has an agenda against contemporary boxing. It turns out his only bias is against uncritical thinking.

But on the topic of modern-day boxing, he has much to say. In “A World of Professional Amateurs,” Silver takes his scalpel to what he views as a growing pattern of prizefighters who find no reason to break out of their juvenile shells. In one passage he praises the skill-set of Dmitry Bivol, the current WBA titleholder who amassed more than 300 bouts in the amateur ranks, but laments his professional instincts.

“Forty years ago, Dmitry Bivol would have been labeled a hot prospect and maybe in line for a semifinal in Madison Square Garden,” Silver writes. “But as good as he is, Dmitry would not be ready to challenge a prime Victor Galindez, the reigning world light heavyweight champion.”

He notes later, in a sharp observation, that “Dmitry won’t be required to improve much beyond his current skill level because the line that once separated top amateur boxers from top professional boxers has become blurred.”

He also takes to task Sergey Kovalev, regarded as the top light heavyweight of the 2010s but who, in his more recent bouts, has revealed the cavernous limitations in his craft. His rematch against Andre Ward, in which he was stopped controversially by a low blow, and his title defense against Eleider Alvarez, in which he was knocked out, were the major tells.

“A seasoned pro who is knocked down or hurt would have known how to tie up his opponent in a clinch or bob and weave his way out of trouble, or at least make the attempt,” writes Silver. “Kovalev, used to knocking out inferior opposition, didn’t know what to do when the situation was reversed and it was he who was in trouble.”

And then there are the interviews. Archie Moore, Emile Griffith, Carlos Ortiz, Ted Lowry, and Curtis Cokes round out a section of illuminating conversations toward the end of the book. They are like the equivalent of Paris Review interviews, primary documents that preserve the wit and inflection of voices too seldom heard. For example, in his talk with heavyweight Lowry, Silver asks him to describe the punching power of Rocky Marciano, whom he came close to defeating, were it not for the judges’ decision. Lowry responds with an illuminating metaphor.

“He hit hard but a smart fighter had no business getting hit by Rocky because he would send you a letter when he’s gonna punch,” Lowry said.

Speaking of letters, The Night the Referee Hit Back is an eminently fine one.

The Night the Referee Hit Back

by Mike Silver

Rowman & Littlefield, 249 pp., $34.00

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision