Featured Articles

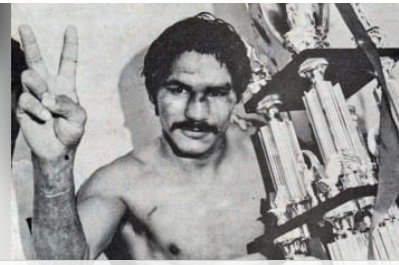

Remembering Oscar ‘Shotgun’ Albarado (1948-2021)

Former world junior middleweight champion Oscar “Shotgun” Albarado passed away on Feb. 17 at age 72 in a nursing home in his hometown of Uvalde, Texas. Albarado’s death didn’t go unnoticed in the town that he put on the sporting map, but news out of Uvalde appears to travel to the outside world by Pony Express. There’s been no notice of it in the boxing press; even the authoritative boxrec has yet to acknowledge his passing. This isn’t uncommon. A boxer has a high probability of dying in obscurity, even if he had a large fan base during his heyday.

The folks in Uvalde had a big shindig to honor Albarado after he won the title; a barbecue at the fairgrounds. “All Texas and especially the city of Uvalde share pride in your accomplishments,” read a proclamation from the Governor of Texas, Dolph Briscoe.

The date was June 20, 1974. Sixteen days earlier, Albarado had wrested the 154-pound title from Koichi Wajima in Tokyo. Down two points on two of the scorecards through the 14 completed rounds, Albarado took the bout out of the judges hands, knocking Wajima down three times and out in the final stanza.

It was a long road to Tokyo. An eight-year pro, Oscar had at least 55 pro fights under his belt when he was granted a crack at the title. As he was scaling the ladder with occasional missteps, he became a fan favorite at the Olympic Auditorium, the shrine of Mexican-American boxing in L.A. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Albarado’s parents were migrant farm workers. They spent a portion of each year picking sugar beets in Minnesota. The kids went along with them. Albarado was purportedly six years old when he first worked in the fields.

He was 17 years old when he had his first documented fight, a 4-rounder in San Antonio, but there are some reports that say he was fighting in Mexico when he was as young as 15.

Albarado became a local attraction in South Texas and then spread his wings, moving to Los Angeles where there was better sparring and boxers of Mexican extraction were a more highly-valued commodity. He was backed by LA fight functionary Harry Kabakoff, a wheeler-dealer who knew all the right people. A colorful character, Kabakoff, born Melville Himmelfarb (don’t ask) had struck it big with bantamweight Jesus “Little Poison” Pimentel, a boxer he discovered while living in Mexicali.

Billed as the Uvalde Shotgun and eventually as just Shotgun Albarado, Oscar had his first fight at the Olympic on Jan. 9, 1969, and four more fights there in the next three months. He lost the last of the five and with it his undefeated record to Hedgemon Lewis who out-pointed him in a 10-round fight. There was no shame in losing to Hedgemon, an Eddie Futch fighter who went on to become a world title-holder.

Albarado was back at the Olympic before the year was out. All told, he had 17 fights at the fabled South Grand Street arena, going 13-3-1. His other losses came at the hands of Ernie “Indian Red” Lopez (L UD 10) and Dino Del Cid.

Del Cid, dressed with a 29-8-2 record, was a Puerto Rican from the streets of New York or a Filipino, depending on which LA newspaper one chose to read. Apprised that Albarado was a slow starter, he came out slugging. A punch behind the ear knocked Albarado woozy and the ref stepped in and stopped it. It was all over in 81 seconds.

Oscar demanded a rematch and was accommodated. Six weeks later, he avenged the setback in grand style, decking Del Cid three times in the opening stanza and knocking him down for the count in the following round with his “shotgun,” his signature left hook.

As the house fighter, Albarado got the benefit of the doubt when he fought Thurman Durden in January of 1973. The decision that went his way struck many as a bit of a gift. But the same thing had happened to him in an earlier fight when he opposed fast-rising welterweight contender Armando Muniz.

As popular as Alvarado was at the Olympic, his pull paled beside that of young Muniz. Born in Mexico but a resident of Los Angeles from the age of six, Muniz attended UCLA on a wrestling scholarship before finishing his studies at a commuter school and had represented the United States in the 1968 Olympics while serving in the Army.

Muniz vs. Alvarado was a doozy. We know that without seeing the fight as we have the empirical evidence in the form of the description of the scene at the final bell; appreciative fans showered the ring with coins. The verdict, a draw, met with the approval of the folks in the cheap seats, but ringside reporters were of the opinion that “Shotgun” was wronged. The LA Times correspondent had it 7-2-1 for the Texan.

Oscar had two more fights after avenging his loss to Del Cid before heading off to Tokyo to meet the heavily-favored Wajima who was making the seventh defense of his 154-pound title. Two more trips to Tokyo would follow in quick succession.

Albarado made the first defense of his newly-acquired belt against Ryu Sorimachi. He stopped him in the seventh round, putting him down three times before the match was halted. Three-and-a-half months later, he gave the belt back to Wajima, losing a close but unanimous decision in their rematch.

Oscar quit the sport at this juncture, returning to Uvalde. He was in good shape financially. He had used his earnings from his Olympic Auditorium fights to open a gas station. With the Tokyo money, he expanded his holdings by purchasing a laundromat.

This would be a nice place to wrap up this story. Former Austin American-Statesman sportswriter Jack Cowan, a Uvalde native, recalled that when Oscar opened his service station, he gave his new customers an autographed photo of himself in a boxing pose inscribed with the words “Oscar Albarado: The Next World Champion.” He would make that dream become a reality, defying the odds, while breaking the cycle of poverty in his family. Boxing was the steppingstone to a better life for him and his children.

But ending the story right here would be disingenuous. This is boxing, after all, and when the life story of a prominent boxer comes fully into a focus, a feel-good story usually takes a wrong turn.

Oscar got the itch to fight again. Sixty-seven months after walking away from boxing, he resumed his career with predictable results. He was only 34 when he returned to the ring, but he was a shell of his former self, an old 34.

Albarado was knocked out in five of his last seven fights before leaving the sport for good with a record of 57-13-1 (43 KOs). He made his final appearance in Denmark, the adopted home of double-tough Ayub Kalule who whacked him out in the second round.

Albarado’s obituary in the Uvalde paper was uncharacteristically blunt. “He suffered from pugilistic dementia,” it said, “caused by repeated concussive and sub-concussive blows.”

There was no sugar-coating there, no Parkinson’s to obfuscate the truth.

If he had known the fate that awaited him, would he have still chosen the life of a prizefighter? That’s not for us to say, but author Tris Dixon, while researching his new book, interviewed a bunch of neurologically damaged fighters and almost to a man they said they would do it all over again.

Albarado had four children, three sons and a daughter. When he was elected to the West Coast Boxing Hall of Fame in 2017, he was too decrepit to travel, but all four of his children — Oscar Jr, Emmanuel, Jacob, and Angela — made the trip to North Hollywood to accept the award on his behalf.

The kids were proud of their old man, a feeling that did not dissipate as he became incapacitated. If boxing was helpful in tightening the bond, then it’s a fair guess the Uvalde Shotgun had no regrets.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 days ago

Book Review2 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds