Featured Articles

Boxing at the Paris Olympics: Looking Ahead and Looking Back

One hundred years ago, Paris was the host city for the Summer Olympics. What goes around, comes around.

In the upcoming Paris Games, boxers will compete for medals in 13 categories. The number remains unchanged from Tokyo, but the ratio has been modified. In Tokyo, there were eight weight classes for men and five for women. The men have lost one and the women have gained one, so in 2024 it is seven and six.

Eight American boxers made it through the qualifying tournaments and will represent Uncle Sam in the City of Lights.

The U.S. boxing contingent in Paris

Men

Roscoe Hill, flyweight (51 kg), Spring TX

Jahmal Harvey, featherweight (57 kg), Oxon Hill, MD

Omari Jones, middleweight (71 kg), Orlando, FL

Joshua Edwards, super heavyweight, Houston, TX

Women

Jennifer Lozano, flyweight (50 kg), Laredo, Tx

Alyssa Mendoza, featherweight (57 kg), Caldwell, ID

Jajaira Gonzalez, lightweight (60 kg), Montclair, CA

Morelle McCane, welterweight (66 kg), Cleveland, OH

Paris, 1924

At the Paris Summer Games of 1924, boxers competed for medals in the eight standard weight classes. The competition was restricted to men. Female boxers were excluded until the 2012 Games in London where the women were sorted into three weight classes: flyweight, lightweight, and middleweight.

Twenty-seven nations sent one or more boxers to the 1924 Games. In total, there were 181 competitors. The United States and Great Britain had the largest squads. Each sent 16 men into the tournament, the maximum allowable as each nation was allowed two entrants in each of the weight classes.

The United States and Great Britain each walked away with two gold medals. The other gold medal winners represented Denmark, Norway, Belgium, and South Africa. But the U.S. team garnered the most medals, six overall including two silver and two bronze, two more than the runner-up, Great Britain.

What’s interesting is that three of the six U.S. medalists came out of the same gym, the Los Angeles Athletic Club. They were proteges of the club’s boxing instructor George Blake who would go on to become one of America’s top referees. The trio included both gold medalists, flyweight Fidel LaBarba and featherweight Jackie Fields, and silver medalist Joe Salas who had the misfortune of meeting Fields in the finals.

LaBarba and Fields were mature beyond their years. LaBarba was 18 years old and hadn’t yet completed high school when he secured a berth on the U.S. Olympic team. Fields, a high school dropout, was even younger. He was 16 years, five months, and 11 days old on the day that he won his gold medal. That remains the record for the youngest boxer of any nationality to win Olympic gold.

Fields and LaBarba both went on to win world titles at the professional level. Let’s take a look at their post-Paris careers. We will start with Fields and save the brilliant LaBarba for another day.

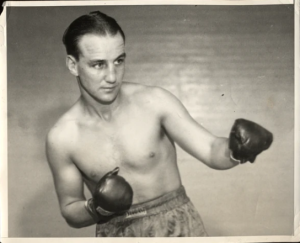

Jackie Fields

Jackie Fields was born Jacob Finkelstein in the Maxwell Street ghetto of Chicago. His father, an immigrant from Russia and a butcher by trade, moved the family to Los Angeles when Jackie was 14 years old.

Jackie Fields

Fields turned pro in February of 1925. Despite his tender age, he was fast-tracked owing to his Olympic pedigree. But his manager Gig Rooney blundered when he put Jackie in against Jimmy McLarnin in only his seventh pro fight. A baby-faced assassin, born in Northern Ireland and raised in Canada, McLarnin, destined to be remembered as an all-time great, was more advanced than Jackie and blasted him out in the second round.

Fields rebounded to win his next 16 fights. His signature win during this run was a 12-round newspaper decision over Sammy Mandell, the Rockford Sheik. Mandell was the reigning world lightweight champion, but because this was officially a no-decision fight, a concession to Mandell, the title could not change hands unless Fields knocked him out.

Fields’ skein ended at New York’s Polo Grounds where he was out-pointed across 10 rounds by Louis “Kid” Kaplan, a 108-fight veteran and former world featherweight title-holder. But Fields built his way back into contention and claimed the world welterweight title in March of 1929 by winning a 10-round decision over Young Jack Thompson at the Chicago Coliseum. They fought for the title vacated by Joe Dundee who was stripped of the belt for failing to defend his title in a timely manner.

The jubilation that Fields felt in winning the title was tempered by an ugly incident in the eighth round when a race riot broke out in the balcony. One man died when he jumped or was pushed off the balcony and scores were injured; “more than thirty” according to one report. Many ringsiders, to avoid flying objects, took refuge inside the ropes but the contest continued after the disturbance was quelled and the ring was cleared.

Fields made the first defense of the title against Joe Dundee. They fought at the Michigan State Fairgrounds in Detroit before an estimated 25,000.

Fields had Dundee on the canvas twice before Dundee was disqualified in the second round for a low blow. The punch was clearly intentional. Fields, to his great distress, wasn’t wearing a protective cup. Heading in, Joe Dundee was still recognized as the champion in New York, so one could say that Jackie Fields unified the title.

After a series of non-title fights, Fields lost the belt to old rival Young Jack Thompson. At the conclusion of the 15-round contest, Young Jack was a bloody mess – he would need to go to a hospital to have his lacerations repaired –but Thompson, who also came up the ladder in California rings, was fairly deemed the winner. This would be the last collaboration between Fields and Gig Rooney. The wily Jack “Doc” Kearns, who had managed Jack Dempsey and was then involved with Mickey Walker, horned right in and became Jackie’s new manager.

Kearns maneuvered Fields into a match with Lou Brouillard who had wrested the title from Thompson four months earlier and Fields rose to the occasion, winning a unanimous 10-round decision in Chicago to become a two-time world welterweight champion. It was a furious battle, wrote the correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. “[Fields] hit Brouillard with everything but the water bucket.”

After another series of non-title fights, Fields risked his belt against Young Corbett III. They fought at the baseball park in San Francisco before an estimated 15,000 on the afternoon of Feb. 22, 1933.

Fields was damaged goods. He had suffered a detached retina in his right eye in a minor auto accident and there was no cure for it. Corbett III (Rafaele Giordano) was a southpaw which was all wrong for a boxer with blurred vision in his right eye. Jackie fought back valiantly after losing the first five rounds, but lost the decision. The referee’s card (6-3-1 for Corbett III) appeared a tad generous to the loser.

Fields retired after one more fight. A closer look at his final record (72-9-2, 31 KOs) shows that he had 19 fights with 10 men who held a world title at some point in their career, including six future Hall of Famers (Jimmy McLarnin, Louis “Kid” Kaplan, Sammy Mandell, “Gorilla” Jones, Lou Brouillard, and Young Corbett III), and was 12-6-1 in these encounters. He was stopped only once, that by the great McLarnin in Jackie’s seventh pro fight.

Jackie Fields Post-Boxing

Fields wasn’t in good shape financially when he left the sport. His various investments were shambled by the stock market crash of 1929. For a time, he lived in Pennsylvania, first in Pittsburgh and then in Philadelphia where he was a distributor for the Wurlitzer juke box company and a sales executive with a distillery.

In 1957, he purchased an interest in a gambling establishment, the Tropicana Hotel in Las Vegas. (Note: In Nevada, prior to 1967, a state law prohibited public corporations from owning or operating a property that housed a casino. Anyone purchasing one or more shares, called points, had to submit to a background check which did little to stanch the influence of the mob.)

Fields eventually sold his shares, but remained with the Tropicana in a public relations capacity. During the 1970s, he served on the Nevada State Athletic Commission. He passed away in 1987 at age 79 at a nursing home in Las Vegas after being hospitalized for a heart ailment. In 2004, he was inducted posthumously into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

For all that he accomplished as a pro, Fields always insisted that his proudest moment came in Paris. “As I stood there, with the band playing the Star Spangled Banner, I cried like a baby, I was that thrilled.”

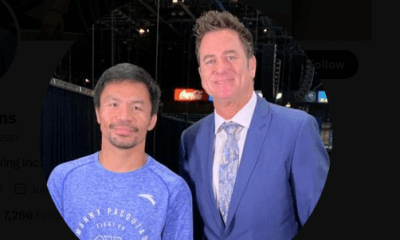

PHOTO: 2024 U.S. Olympian Roscoe Hill

To comment on this story in the Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons