Articles of 2006

Paul Cavagnaro: A Fighter for Life

The restaurant doorman was in his 20s, about 6’6” tall and 250 pounds of slabbed muscle. Paul Cavagnaro was in his mid-80s, and had weathered cancer, two major heart surgeries and a minor stroke. But as he sized up the young goliath holding open the door for him and his wife, Cavagnaro had the same thought that always flashed through his mind in such situations:

“I wonder if I could take him….”

Sixty years ago, after Cavagnaro had just a handful of pro fights, some sportswriters in his native San Francisco were wondering if he could take heavyweight champion of the world Joe Louis.

They never found out, of course, because when his mother couldn’t take the idea of her only son exchanging punches in the boxing ring anymore, Cavagnaro hung up his gloves rather than put her through the anguish.

“If you want to fight,” Eugenia Cavagnaro told him, “join the police force!”

So he did, putting in 30 years on the San Francisco force, becoming an inspector and one of the city’s best and most admired cops. But he never stopped training like a fighter and loving what Cavagnaro still calls “the manliest of all sports.” Today his home in Elm Grove, Wisconsin, where he and wife Ramona moved in 1986, is filled with photos and mementos of the boxers Cavagnaro knew and admired, sparred with and, in some cases, loved like brothers.

Tops in the last category is Richie Shinn, the Korean-American who was his best friend from childhood up to Shinn’s death over 20 years ago. In the 1940s, Shinn was a decorated U.S. war hero and a tough lightweight boxer. “The bravest man I ever knew,” says Cavagnaro of the man who introduced him to boxing when they were growing up together in San Francisco’s North Beach district.

By the time he was 12, Cavagnaro was making things miserable for neighborhood kids who boxed him in the makeshift ring Paul’s father, Gio Batto, set up in their front yard. One day a milkman out making deliveries saw Cavagnaro working over another boy, stopped his truck and ordered him to lay off. Invited by Cavagnaro to put on the gloves himself, the milkman quickly wished he had minded his own business.

Later Cavagnaro joined San Francisco’s famed Olympic Club, whose boxing program was run by the legendary Spider Roach. In Cavagnaro’s first real amateur fight, his opponent was Pat Valentino, who would go on to become a top heavyweight contender and unsuccessfully challenge Ezzard Charles for the title. The more experienced Valentino outpointed him, but when Roach sent Cavagnaro over to congratulate the winner, Valentino was so out of it from a right hand Cavagnaro had tagged him with just before the final bell it was all his handlers could do to hold him up.

Keeping his fighting a secret from his excitable Italian immigrant mother by stashing his boxing gear in the bushes in front of their house, Cavagnaro won local and Pacific Coast Golden Gloves titles as a light heavyweight, and in the spring of 1941 he went to Boston for the Amateur Athletic Union national championships.

After the rigorous cross-country train ride, Cavagnaro weighed only 156 when he fought heavily-favored local boy Tommy Sullivan –– a descendant of the great John L. himself –– in the 175-pound semi-finals. Sullivan was as foul-mouthed as his famous fighting forbearer as Cavagnaro punched him silly to win the decision. But Cavagnaro had nothing left for the finals later that same night, and lost on points to Detroit’s Tom Plesha.

After America entered World War Two the following December, Cavagnaro put boxing on hold and joined the U.S. Coast Guard, serving for four years.

When the war ended, he turned pro under the management of Joey Fox, one of the Coast’s most astute boxing people, with whom Cavagnaro formed a lifelong father-son-like bond. He stopped his first two opponents in the first round, fought a draw, and, after he won a couple more bouts, the Bay area scribes were impressed enough to mention Cavagnaro as a possible future challenger for Joe Louis.

In the fall of 1946, Fox sent Cavagnaro to Los Angeles to train for a while under Fox’s partner, Dutch Meyers. Cavagnaro was dubious about the arrangement, and his confidence in Meyers really nosedived when he heard the latter seriously advance the proposition to George Engle, who’d managed Harry Greb, that Greb wouldn’t have stood a chance in the ring against Bert Colima, a popular West Coast journeyman in the 1920s.

Meyers took his time lining up a fight for Cavagnaro, and finally told him on a Friday that he was meeting Dale Hall the following Monday at the Olympic Auditorium. Cavagnaro headed fight for the Main Street Gym and tore into a sparring partner with such ferocity and skill that everybody in the gym stopped to watch. At the end of the session, Cavagnaro was called over by California Jackie Wilson. “White boy,” said Wilson, a great welterweight of the 1930s and ‘40s, “where’d you learn to fight like that?”

Dale Hall would become a decent heavyweight in time, but Cavagnaro had no problem outboxing him in a fight that went the distance only because the strange Meyers ordered Cavagnaro not to go for a KO.

By then, of course, Eugenia Cavagnaro knew all about her son’s boxing, and not even his opponents suffered as much as she did when he fought. When Paul came home from a bout, he would walk for hours all over town with his mother in an effort to calm her nerves.

But it kept getting worse, and after the Hall fight it was Joey Fox who suggested to Cavagnaro that for his mom’s sake he find another line of work.

As a policeman, Cavagnaro trained just as diligently as he had as a fighter. He did roadwork with his friend Bobo Olson, the 1950s middleweight champion. After running sprints for an hour on a football field, Cavagnaro would hook his feet on the top of a chain-link fence and grind out 500 pushups. A 6’1” and 225-pounds, he was built like Hercules, and needed specially tailored jackets to fit his powerful physique.

Once he ran into fitness guru Jack LaLanne, who took a gander at Cavagnaro’s muscles and wondered how much weightlifting he did to get them. “I’ve never lifted a weight in my life,” Cavagnaro told him. Later that same day, the disbelieving LaLanne got into a heated argument with some of Cavagnaro’s friends on the subject, insisting that nobody could get that sculpted without pumping a ton of iron.

A by-the-book cop, Cavagnaro was admired and respected by his colleagues in blue –– and, on one occasion, feared. When the Police Department went out on strike, Cavagnaro refused to join the picket line and continued to do his job. One day he radioed to headquarters that he was bringing in a murder suspect. The word came back that the striking cops had ringed the building and refused to let anyone in. When he pulled up there, the enraged Cavagnaro leapt out prepared to fight his way inside if he had to. He didn’t. Seeing the look on his face, the picketers quickly got the hell out of his way.

That episode notwithstanding, “Few officers have more friends in the police department,” noted the San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle in 1967, because “from the day back in 1947 when he joined the department and began to work his way through the ranks, (he) has been a good officer.

“But more than that, he has the touch –– in many ways. He wears a size 51 coat because of his wedge-like shoulders. Trainers at the Police Academy think he could give Cassius Clay a good go –– anytime.”

When he retired from the force, his fellow cops presented Cavagnaro with a trophy jokingly inscribed to “Inspector Canvasback.”

After he and Ramona (who wears Paul’s 1940 Pacific Coast Golden Gloves championship medal around her neck on a gold chain) moved to Wisconsin, Cavagnaro turned the basement of their home into a shrine to his boxing heroes, including his great friend Ray Lunny Jr., the 1940s featherweight contender; Eddie Booker, the great Golden State light heavyweight with whom Cavagnaro often sparred; and onetime heavyweight contender Turkey Thompson, who in a gym session gave Cavagnaro two black eyes he wore as proudly as he later did his police shield.

At 88, health issues have slowed him down and made it hard to keep up the heavy bag workouts that he made an art form. But I’d still take him over any hulking doorman, and even some of our current heavyweight contenders.

As for Joe Louis (who Cavagnaro ranks as the best ever heavyweight), who knows what would’ve happened had Cavagnaro not loved his mother even more than boxing. But he regrets nothing, except maybe the time when the man Cavagnaro regards as the greatest fighter in history wanted to spar with him, and Joey Fox said no thanks to Charley Burley.

“He would have killed me,” says Cavagnaro dreamily.

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

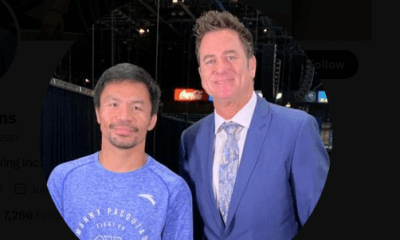

Featured Articles6 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons