Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Light-Heavyweights of All Time Part Three – 30-21

The Fifty Greatest Light-Heavyweights of All Time Part Three – 30-21

Those of you who have followed this series from Part One may notice a slight tonal shift in this third entry describing the fifty greatest 175lb fighters of all time. This is due to our arrival, finally, among the ranks of the inarguable. You cannot devise a top fifty at this weight absent any of the names listed from #30 on down – each and every one of these men has an airtight case for inclusion on this list.

It is no coincidence that as we reach this point we also begin to explore in earnest the 1970s but there are representatives here too of another great decade for the light-heavyweight, the 1920s. Two modern inclusions sparkle also, with the twin jewels of longevity and the long ledger of ranked opponents defeated, as opposed to a handful of legendary opponents defeated, that often define modern greatness.

Finally there’s an early visitation from a true legend of the sport, a man who, for me, is the single greatest fighter in history but whose body of work at 175lbs doesn’t demand as high a ranking upon this list as might be imagined. It surprised me – but the work and the criteria that support it tell this division’s story.

#30 – VIRGIL HILL (51-7)

As legendary baseball player Lefty Gomez put it, it’s better to be lucky than good. Virgil Hill benefited from more than a little of both in a career that saw him meet as many fighters ranked at some point in the Ring Magazine top ten as just about anybody on this list. Perhaps the fact that luck kept him safe at times during such a difficult career is more forgivable for that fact.

He stepped up for the first time against the excellent Leslie Stewart, a fight that could have been an extremely dangerous assignment, one that Hill was brave to take on. In truth, Stewart was neatly perched on the edge of old age and two exquisitely timed Hill left hooks tipped him over in four rounds late in 1987. In 1988 and 1989, Stewart went 2-3.

Still, Hill had to do the job and it was feared he might not have the style for it. To put it bluntly, Hill looked every bit the Olympic medallist – the amateur – he was, his weight perched upon his bent leading leg over which he would jab-jab-jab his way to victory. Over time he added a decent right hand, especially to the body but as a converted southpaw, it was always the left that would be his key to victory.

A whole nine years after Stewart, in what may be his defining fight, in Germany, against the world’s then #1 light-heavyweight Henry Maske, Hill was breathless in his amateur stylings despite the addition of that right. He out-peppered Maske in the early rounds, faded in the midsection and by the eleventh was running and clinching enough that it had become embarrassing. Still, he edged that fight on my card 115-113 and astonishingly (there’s that luck again) he was given the decision in a broiling pro-Maske atmosphere. Even more astonishing, this was the second time Hill was awarded an extremely narrow decision over a homeboy having defeated the quality Fabrice Tiozzo, a national hero in France, in his home country in 1993. Tiozzo came close to “finding out” Hill and his amateur style and come the fifth he was just walking in on the American and blasting him. To his credit Hill was so fast and had such a keen sense of when to stand and fight in key rounds that he was able to edge out Tiozzo by a single point for me and by a split decision on the official cards.

He had his fortune at home, too. I thought he was a little lucky to get the nod against speedster Lou De Valle in North Dakota in 1996. Decked by a rather ridiculous counter-left early on, he took on the unfamiliar role of aggressor and at no time looked comfortable, although he was crafty enough to get home for the decision.

Still, there is an awful lot that is impressive in Hill. He recognised his limitations, boxed within them and overstepped them so rarely that it was noticeable when he did so. He won eleven consecutively after smashing a strap out of Stewart, and when it was unceremoniously and rather surprisingly taken from him by Tommy Hearns in 1991 he picked himself up, dusted himself off, and went on another wonderful run terminated only in 1997 by the twin towers of Dariusz Michalczewski and Roy Jones. During those two purple patches Hill out-boxed numerous fighters who held a ranking, and although whenever he stepped into the top five he was usually set for a struggle, the lesser lights and fading stars of the division were generally out-classed, or something like it.

Longevity, a semblance of dominance illustrated right at the end of his time at the top makes Hill was one of the most important light-heavyweights to box between Michael Spinks and Roy Jones.

#29 – JOHN CONTEH (34-4-1)

John Conteh was ranked among the four best light-heavyweights on the planet by Ring Magazine for an astonishing seven years. Such longevity at the very top of the division is almost unheard of, but Conteh established this feat in what was the deepest and strongest light-heavyweight division since World War II.

He was very nearly claimed by the heavyweight division however, and not after he’d done the damage at 175lbs like so many of his peers but before – Conteh cut his teeth on heavyweights and moved down among the smaller men only after his first loss, supposedly upon the advice of Muhammad Ali. He arrived with a splash, crushing incumbent European champion and number five contender, Rudiger Schmidtke in twelve rounds in March of 1973. As always, Conteh collected that title in great style, employing feints (while he himself was almost impossible to feint), jabs (while he himself was almost impossible to outjab) and a spiteful right hand to stop the German in twelve.

These are passing comments on one of the division’s true stylists that hardly capture his essence, however. Conteh’s left-hand should have belonged to a more committed fighter; he was as famous in the UK for shunning his training and his love of the nightlife as he was for his wonderful talents. Both jab and hook were of the absolute highest class and his right, when he dropped it, was a hurtful punch. The right was a Conteh weakness though. He threw it rarely in his later career most especially after breaking it in a car crash, although injuries to both hands plagued him throughout his career. Inactivity married to certain impracticalities in his character also cost him both money and prestige, his refusal to go through with a contest with Miguel Cuello, announced just three days before the fight, hurting him less perhaps than his failure to meet legitimate champion Bob Foster.

Still, Conteh built an excellent resume with his smooth box-punching, besting former beltholder Vicente Rondon in nine, the superb Chris Finnegan who had pushed Bob Foster as hard as he would be during his title run, the hugely experienced Tom Bogs, Jorge Victor Ahumada in his superb strap-winning effort and a defence of that strap in a wonderful fight with Yaqi Lopez.

Unbeaten until the twilight of his career when he was narrowly outfought by both Mate Parlov and Matthew Saad Muhammad, Conteh may not have been so lucky had he hooked up with either Victor Galindez or Foster, but by the time he was stopped for the first time in his career in the rematch with Muhammad, he had already guaranteed himself a place among the greatest and the best light-heavyweights in history.

#28 – BATTLING LEVINSKY (70-20-14; Newspaper Decisions 126-35-23)

The best middleweight just took turns beating up Battling Levinsky in 1911 but when he added pounds and stepped up to the fledgling light-heavyweight division his results improved, a close bout often reported a draw with nemesis Jack Dillon his first reward. Dillon dominated a ten fight series between them, Levinsky managing no better than 2-2-6 by some counts, certainly losing their twin battles for Dillon’s generally recognised light-heavyweight title claim in 1914, but Levinsky crept closer as Dillon began to suffer ring wear, finally dominating and taking from him the title in late 1916. It is the series which trails Levinsky’s growing maturity just as it trails Dillon’s decline.

Levinsky’s problem against Dillon was that he lacked pop, scoring, as he did, only thirty knockouts in nearly three hundred bouts. Dillon over and again would out-punch Levinsky who, while brilliant defensively and expert at avoiding sustained punishment, could not remain ahead of Dillon’s offence entirely.

In the No Decision era, where unofficial rulings were made by attendant newspapermen, this may have been especially hurtful to Levinsky because some accounts of his record did not recognise Newspaper Decisions, listing only the wins he achieved by rare knockout or by official decision in states where they were permitted. This, Levinsky countermanded by a schedule so busy as to be comparable to that of the great Harry Greb, boxing nine times in the first month of 1914 for example.

As well as his eventual victories over Dillon, Levinsky defeated Charley Weinhart, Leo Houck, Bartley Madden, Clay Turner, Gunboat Smith (who also defeated him) and Mike McTigue, but it is a fact that, at light-heavyweight, Levinsky was normally beaten whenever he stepped up in class. Dillon got the best of him, he was repeatedly thrashed by Greb, lost a fight with Young Stribling which was so bad it was suggested that Stribling may have carried him, was beaten in twelve by Gene Tunney who savaged him to the body, and was stopped in four by Georges Carpantier, relinquishing the title to him. Although he mastered Billy Miske up at heavyweight, he was outfought in their single meeting at or around light-heavyweight (also losing a second contest in that range if we stretch our definitions by a pound). In short, the best light-heavyweights tended to beat Levinsky – and I think that this is a fact that is historically ignored by the likes of Nat Fleischer (who ranked him at an astonishing #6 on his ATG list for the weight). I take some comfort in the fact that the IBRO ranked him all the way down at #20, and that Charley Rose left him off his own ATG list, written in the 1960s. It is also true that early in his own career, Levinsky was identified by former heavyweight champion James J Corbett as a fighter who would prosper for the most part only against what he called “second and third raters”. While this is a little stronger than the language I would use, I believe it was born out to a degree.

Still there is no denying that this is my first serious disagreement with boxing history as it is generally held, and I wish to temper troubled waters by stating that Levinsky clearly belongs on this list. His longevity was astounding, having been favoured over Eddie McGoorty in 1912 and relevant to the light heavyweight division as late as 1921 when he defeated the heavily outweighed Mike McTigue. In between, he fought often and well enough that he ranks here over men who have perhaps taken better scalps but cannot match him for complete body of work.

#27 – MARVIN JOHNSON (43-6)

Marvin Johnson was light-heavyweight’s greatest pure thug. By the end of his career, which somehow chugged into the late eighties, making him one of the great survivors of the stacked 1970s division, he was an ancient and rusted battleship that took too long to turn to maintain effectiveness. At his best he brought some of the most direct, wicked pressure in the division’s history, not crafty enough to ever defeat one of the true monsters with whom he shared a ring but devastating enough that anyone else was filleted.

Unfortunately for Johnson he came crashing into the most stacked light-heavyweight division in history. Leslie Stewart, Eddie Davis, Charles Williams, Michael Spinks, Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, Victor Galindez and Mate Parlov all lay in wait, but the first monster he ran up against was Matthew Saad Muhammad. Both men were still prospects (Muhammad a controversial 15-3-2, Johnson 15-0) but they turned in perhaps the greatest fight ever fought at 175lbs. Johnson was beaten by a knockout in the twelfth, the walking dead long before hit the canvas having launched the kind of devastating and absurd attack in the first that always leaves a fighter vulnerable past round seven. Still, it was one of those rare losses that actually enhances a fighters standing such was the degree of heart, punch resistance and persistence that Johnson demonstrated. Their rematch, fought for the strap then in Johnson’s possession almost exactly one year later, was almost as dramatic, Muhammad again the winner, again by stoppage.

Between these two losses, Johnson lifted that strap against the difficult and excellent giant Mate Parlov in Italy. Parlov, who had knocked out Miguel Angelo Cuello for the title before repelling John Conteh in his first defence, was nothing more than target practice for Johnson. The great Victor Galindez lasted barely longer and although faded, watching Galindez, perhaps the division’s greatest matador, duel with Johnson, perhaps the division’s greatest bull is one of the great thrills in boxing. Of course Johnson was never in a bad fight although this was not always for the best of reasons. His jab was perennially under-fuelled and sometimes an outright liability and he was far too easy to hit. Eddie Mustafa Muhammad took advantage of these weaknesses to see him off in eleven, and Michael Spinks threw one of the best punches of his career to see him off in four, but often Johnson rolled over ranked, made men like Eddie Davis as though they weren’t there.

This was the pattern he bowed to in his career, generally losing to the best he fought but dominating or finding out everyone else. Unexpected, winging combination punching, an enormous heart, fearlessness and perhaps the best trailing uppercut at the weight make him one of the most formidable beasts ever to make a career at 175lbs. Many other eras would have made him a great champion.

#26 – DARIUSZ MICHALCZEWSKI (48-2)

Dariusz Michalczewski took the lineal light-heavyweight championship from Virgil Hill in 1997 and did not lose it until 2003 when time and Julio Cesar Gonzalez caught up with him. It does not matter that Ring Magazine gifted Roy Jones their title in appreciation of his brilliance – Michalczewski was the real champion, and you have to go all the way back to the great Archie Moore to find one who ruled for more years.

Of course there the comparisons end. Michalczewski packed in an astonishing fourteen successful defences while on top of the hill. His opposition was sometimes less than inspiring and he certainly didn’t do the damage to the division that Roy Jones managed (as we shall see) but he won his fair share of big fights. Against Virgil Hill he did what Henry Maske couldn’t and solved Hill as early as the second round, unveiling his lack of power and taking risks to cut off the ring on his fleet-footed foe. When Hill tried for volume, Michalczewski just picked punches, unerringly finding the right blow before going right back to his stalk and destroy style. The fight was not close.

He showed more superb adaptions versus ranked stylist Lee Barber, a road-warrior who found himself picked and re-picked by an inexperienced fighter who again and again found a perfect mid-range to outpunch the bigger man in neat, controlled bursts. He needed a granite chin to win a 1999 shootout with Montell Griffin but became only the second man ever to stop the American when referee Joe Cortez interceded as Michalczewski brutalised him against the ropes. Graciano Rocchigiani, who caused Henry Maske all those problems, was battered to the only stoppage loss of his career. Lesser ranked men like Derrick Harmon, Richard Hall and Drake Thadzi tended to be stopped. Michalczewski was dominant like Wladimir Klitschko is dominant and although, like Wladimir, he arguably never had that legacy fight so needed to silence doubters, the many years he spent at the top of the division must be recognised and rewarded.

#25 – TIGER JACK FOX (139-23-12)

Tiger Jack Fox went 0-1-1 against Maxie Rosenbloom up at heavyweight, perhaps unlucky to receive the draw, but their single meeting at 175lbs went the way of one of the greatest fighters never to win the light-heavyweight title. In the fourth round of that meeting, Fox forced Rosenbloom to his knees for a flash knockdown, inevitably landing the harder punches throughout to take a decision characterised by The Spokesman Review as “fairly well received by the crowd.” This was the best result of Fox’s career. He came up short against John Henry Lewis, blasted into unconsciousness by him in just three, which was unfortunate as Lewis held the title to which Fox became the #1 contender.

He came up short, too, against Melio Bettina when he finally got a crack at a strap (if not the legitimate title) in 1939, by which time Fox had been a professional for eleven years. Worse, in the run up to the fight he had received a serious stab wound to the chest. Carl Beckwith of the Washington Afro-American noted a week before the fight that “Fox doesn’t look at all ready” and even had difficulty climbing in and out of the ring. It is typical of the hard-luck stories surrounding top black contenders of this era that when Fox’s shot comes he carries an unusual and debilitating injury into the ring with him. Such was the life of an Afro-American fighter of this era.

Not that Fox was perfect. He was given to stalling and according to the Spokane Daily Chronicle “for all his clowning…he is potentially a great fighter – but this is fair warning…[that fans] would rather see him find a steady pace and stick to it.” Still, he built a superb resume despite the prejudices of the era and his own limitations avenging a loss to Al Gainer over fifteen, destroying former divisional champion Bob Olin in just two, smashing out top contender Leo Kelly in six and generally crushing any of the minor light-heavyweights who dared to step into the ring with him.

Much of his very best work was achieved at heavyweight, and this must be remembered by those hardcore history-buffs that would like to see him higher.

#24 – SAM LANGFORD (179-30-39; Newspaper Decisions 31-14-16)

Sorry, Sam.

In his excellent series for Boxing Scene Cliff Rold ranked Sam Langford at #2 for this weight. Herb Goldman agrees with him exactly. The IBRO rank him one space lower at #3. And here I am telling you Sam Langford is the twenty-fourth greatest light-heavyweight of all time. How can this be justified?

In Part One I wrote:

“[F]ights fought by fighters usually held to be light-heavyweights contested above the light-heavyweight limit, will be considered to have engaged in a heavyweight contest and will not be credited here. As a rough guide, fighters matched at below 164lbs are generally held to have fought a middleweight contest and fighters matched at 180lbs and above are fighting at heavyweight. Also the weight class in question is always defined by the heavier fighter. If a 173lb man is fighting a 203lb man, he is engaging in a heavyweight contest. This list is interested almost exclusively in fights that took place within the light-heavyweight class.”

And I stand by that.

Whatever the criteria used by the IBRO, Boxing Scene or Herb Goldman, matches actually fought in the weight class light-heavyweight are not among them – or at least, fights that were verifiably between light-heavyweights are not among them. Between the vast collection of newspaper articles made available by The Library of Congress, details of Langford’s fight on Boxrec and the superb work put in by Clay Moyle for Sam Langford: Boxing’s Greatest Uncrowned Champion, I have been able to verify just a handful of contests actually fought by Sam Langford at the weight in question. Langford graced the light-heavyweight division for some years in terms of his own weight, but most of the significant fights he fought, even with some allowances made for the fact that the middleweight title was often contested at a lower weight in his era, were against opponents who were in another division, usually heavyweight.

In 1906 he famously weighed in at 156lbs for his meeting with all-time great heavyweight Jack Johnson; he was a middleweight. He made it into the light-heavyweight division in 1908 and met 190lb heavyweight Jim Barry, heavyweight Black Fitzsimmons, two-hundred pounder Joe Jeannette, middleweight journeyman Larry Temple, heavyweight contender Sandy Ferguson…you get the point.

Nevertheless, Langford did enough work that he cannot be ignored all together. He has battered his way into the top twenty-five here based upon his obliteration of Fireman Jim Flynn (KO1), his mauling of the wonderful Jeff Clarke (KO2), a battering of Jack O’Brien from 1911 that barely meets our criteria and a handful of other victories that fall into the correct weight range. Additionally there is the spooky sense that Langford imbues that he might have beaten the majority of the fighters who will make up the top twenty.

For those who feel I am underestimating Langford: I consider him the single greatest fighter of all time pound-for-pound. I think he is greater than Ray Robinson – better than Henry Armstrong, even more extraordinary than Harry Greb; but he achieved only a smidgen of what Harry Greb did in the light-heavyweight division. This is the true reflection of Sam’s wonderful career, and it shouldn’t be coloured by the rainbow of his incredibly performances below and above this division.

It looks horrible and I acknowledge that, but the truth often does.

#23 – YOUNG STRIBLING (223-13-14; Newspaper Decisions 33-3-3)

Young Stribling’s career is an absurdity in so many ways there is likely not enough room here for me to list them all. First among them is that he engaged in around 300 recorded contests (likely many more) and that he was only stopped once, in the fifteenth round, against the borderline great heavyweight Max Schmeling. He was never stopped at the 175lb limit.

More absurd: his one and only crack at the world’s light-heavyweight championship. The title was in the possession of Mike McTigue, an uninspiring figure as a champion and one who retained his title against Stribling in bizarre circumstances. The promoter claimed that ringsiders saw the fight almost universally for Stribling but that the referee refused to render a decision at the end of the ten rounds. Stories circulated that the official was under threat of death, although who was meant to carry out his assassination and for what reason was not made clear – finally the referee buckled and rendered a decision for Stribling. Three hours later he withdrew that decision and called the fight a draw, meaning McTigue would retain his title. The champion claimed to have been sent to the ring “at gunpoint” with a broken hand – with two working hands and nobody pointing a weapon at him, he was firmly out-pointed by Stribling once more the following year in a non-title fight.

Stribling also handed the young Tommy Loughran two “artistic beatings”, split the best end of a pair of no-decisions with Jimmy Delaney, lost a six-rounder to the king of that distance, Jimmy Slattery, but took an uncharacteristically violent revenge upon him some years later, roughing him up on the way to a ten round decision win. He dropped Maxie Rosenbloom on the way to another great victory in 1927, having out-worked an ageing Battling Levinsky the year before. He beat so many greats and champions that fighters like Lou Scozza, key wins for men further down the list, become window-dressing on Stribling’s fabulous record. He kept piling up wins out of the top drawer (and, it must be acknowledged, a huge amount of dross) up until 1933 when he was killed in a motoring accident. He was 28 years old.

In terms of weaknesses, he lacked a certain savagery and certainly in newspaper reports of the time and the scant footage that survives he doesn’t look what the old-time sportswriters would have referred to as “a killer”. But this weakness hardly manifested itself in losses. Judges and newspapers both tended to find for rather than against him, and no light-heavyweight got close to laying him low with punches.

Clever, quick, a stiff puncher with a wonderful fighting-brain, it is one of boxing’s greatest shames that he was never the champion, most especially with his having beaten an incumbent title-holder twice.

#22 – PAUL BERLENBACH (40-8-3; Newspaper Decisions 1-0-0)

Paul Berlenbach was one of light-heavyweight’s finest punchers, thirty-four of the forty-one victories he is credited with coming by way of knockout. He was a ring savage, easy to hit but almost impossible to dissuade, boasting a great chin and one of the most damaging body attacks of the era. A wonderful balance of strength and weakness raised him up onto the cross of great fights. These, Berlenbach delivered, and soon, beginning his terrible rivalry with Jack Delaney (already world class) in just his fifth month as a professional, losing in four rounds. “They practically ruined each other,” boxing correspondent Robert Edgreen would write in 1927, as Berlenbach’s career began to wind down. Practically, Berlenbach coming off the worse as Delaney’s stylistic approach proved the more sustainable, bringing him a clean victory in their desperate series. Berlenbach did have his moment though, successfully defending the world title he had ripped from Mike McTigue in May of 1925 against his nemesis in December of that same year. In the fourth, Delaney landed a “mule-kicking” right to Berlenbach’s jaw the effects of which rippled in the latter’s nervous system as late as the seventh when he seemed in immediate danger of losing his title, and would have in a more civilized era. Spared by the 1920s referee, Berlenbach battled back to drop Delaney in the twelfth and take the narrowest of decisions over the man who had already stopped him and who would stop him again; it was the most important win of his career.

Despite Delaney’s overall domination of him, Berlenbach didn’t suffer as badly with other world-class boxers. Young Stribling, like Delaney, could punch as well as box but he got little out of Berlenbach when they met in the summer of 1926. Berlenbach thrashed him, dishing out what was “the only real beating Stribling had ever taken in his life” according to his lifelong friend Milton Wallace. Frank Getty of United News described Stribling as “a punching bag” and rated him good for only two of the fifteen rounds. Berlenbach, so late to the theatre of pugilism, outhustled and outfought a man groomed for the ring since birth.

Berlenbach also “slaughtered” Battling Siki according to the New York Times, battered out Jimmy Slattery in eleven and out-pointed contender Tony Marullo and if his drop off was sharp, if he went from fistic catastrophe to past-it contender a little too swiftly to be ranked here with the true elite, it is beyond doubt that he deserves to be included in the prestigious company he finds himself in now.

#21 – DWIGHT MUHAMMAD QAWI (41-11-1)

Dwight Muhammad Qawi went just 19-2-1 at light-heavyweight; then he vanished not to heavyweight but to cruiserweight, where he gave Evander Holyfield one of the toughest fights of his career, a war that also happens to be one of the best fighters in history.

Qawi was the light-heavyweight Joe Frazier, a terrifying prospect, comically small at just 5’7 but an educated pressure monster who brought war in the form of punches.

He was too much for Matthew Saad Muhammad. Muhammad is one of the greatest light-heavyweights in history and he lurks somewhere above among the true giants of the division but Qawi kicked hell out of him not once but twice, for the first time in 1981 and then again in 1982. It has been said that Muhammad was past his prime at the time of his first meeting with Qawi, and I have a certain degree of sympathy with that point of view – however, it is worth pointing out that Muhammad came into the Qawi contest on the back of seven straight stoppage victories at title level, including the destructions of John Conteh, Yaqui Lopez and Lottie Mwale. Nevertheless, he did struggle to make weight, and against a fighter whose nickname is Buzzsaw, draining is never going to make for a particularly pleasant night. Qawi’s plan was to move across Muhammad, bringing the pressure that made him so dangerous but doing it with angles, attempting to stay ahead of the beltholder while opening up his body. It worked. From the first Qawi is landing jabs to the body and making room for his right hand, from the start Muhammad strained to find him. He may have won the first; Qawi took every other round before stopping him with truly chilling show of precision and calm. Their rematch, fought nine months later, was even more one-sided.

Between his matches with Muhammad, Qawi crushed the excellent Eddie Davis, having already twice avenged a controversial, perhaps even nonsensical defeat to his namesake, Johnny Davis. Mike Rossman, who had once defeated the great Victor Galindez, managed just seven rounds before he succumbed. James Scott, who had famously defeated Eddie Mustafa Muhamad behind the walls of Rahway State Prison did less well when Qawi signed the visitors book. It was speculated that Eddie Mustafa had been intimidated by his surroundings and perhaps even by Scott; it was Scott who uncharacteristically went on the run in the first however, Qawi following with a sick grin. A unanimous decision soon followed.

The other man to have bested Scott was Jerry Martin. Qawi tracked him down and stopped him in six. Qawi wasn’t at light-heavy long, but while he was, contenders tip-toed past, holding their breath.

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

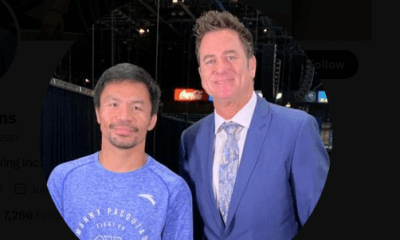

Featured Articles7 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons