Featured Articles

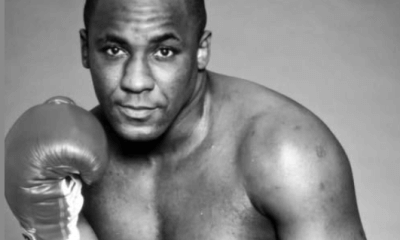

‘How To Box’ by Joe Louis: Part 5 – Defense

‘How To Box’ by Joe Louis: Part 5 – Defense

He was a master on defense.”—Nat Fleischer

The judgment of the founder of The Ring magazine is not to be ignored but nor can it be allowed to go unremarked that many of his most prestigious contemporaries disagreed with him, some quite vehemently. The great newspaperman Grantland Rice was amongst them:

“On the defensive side there is still a lapse between mind and muscle. A break in an important co-ordination.”

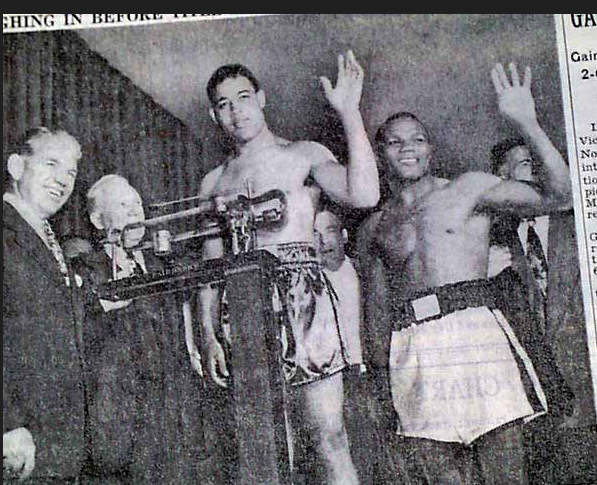

I have sympathy with both points of view. Louis is at heart an offensive machine. This is something of a cliché, but where certain high-end boxers are concerned—Dempsey, Louis, Tyson—it is applicable. Offensive machines are limited in defense, traditionally, a situation which is entirely natural. Getting the punches across becomes the most important thing for these men and in turn that determination makes the opponent nervous about punching—this is the first line of defense for any great hitter and Louis was no different. It was a brave man who planted his feet when sharing the ring with him. Nevertheless, even the most aggressive of boxers must have solid defensive technique to become successful at the highest level. As described in Part One—The Foundation of Skill, Joe laid some of the nuts and bolts of these techniques bare in How to Box, the manual released in his name after his triumphant return bout with Jersey Joe Walcott. Through Parts Two, Three and Four we’ve taken a close look at Joe Louis on offense using Joe’s ghost-written instructions in tandem with a detailed look at Louis on film, and putting defense under the microscope is going to be no different. In the other corner for this most difficult subject is one of Joe’s most difficult opponents—Jersey Joe Walcott.

Speaking in 1941 of the then absolutely primed version of Joe Louis, Billy Conn’s trainer Johnny Ray said before Louis-Conn I:

“You guys have got it all wrong. You don’t box Joe Louis. You can put all the boxers you like in front of him and he’ll find them. No, you need to fight Joe Louis. You need to fight Louis every minute of every round, you need someone who can take his punches and give him some back. That’s how you beat him.”

The great Conn came within touching distance of doing just that before succumbing to the inevitable. Now Walcott set out to find a combination of the two strategies described in Ray’s informed outburst that would be the past-prime champion’s undoing. His mission statement was nothing less than the literal perfection of boxing’s defining mission statement, one that will be repeated a thousand times in gyms across the world this very day in one form or another: hit and don’t be hit. Walcott spent fleeting, desperate moments in the pocket always looking for the exit just before Louis hit his stride, exchanged with him at distance but always trying to force Louis to lead in unfavourable moments, then vanishing in a series of sudden, unpredictable moves that left a fuming Louis resetting his stance over and over again. Louis does not seem to have landed a single straight right hand of real import in the twenty-six rounds spent in Walcott’s company. Readers of Part Three will understand the significance of this.

Jersey Joe stretched Louis to the absolute limit on offense but also on defence and in all likelihood it is amongst his worst performances in this regard, but this is a fight I wanted to take a closer look at before this series was concluded. So, I’m breaking one of my own rules and examining a fight of which apparently only highlights have survived—Louis-Walcott I.

In the opening moments of that fight’s first round, Louis demonstrates his most crucial defensive skill, the slip. In How to Box this is described as a technique “used against straight leads and counters. As your opponent leads with his left, shift your body about five or six inches to the right of the blow, making it fall harmlessly over your shoulder…sometimes it is only necessary to move your head to slip a punch.”

This is a key skill for Louis and one that allowed him to consistently out-jab opponents over the course of his career, even those who out-reached him.

After being caught with two clipping Walcott jabs early, Louis slipped the third in this manner. What is crucial to note about the Louis defence is that it is built specifically to facilitate offense. After the punch is slipped, How to Box tells us that we should find ourselves in position “for a blow to his unprotected left side.” This is the theory, in practice Louis comes out of the slip to throw a punch at Walcott’s right side before following it up with a short straight. It is Louis’ early warning that the angles Walcott will be showing will not be of the type he has been shown in the gym.

It’s also an early lesson in the way that Louis wove his complete offense together with his less astonishing defence to create a pattern of deterrent that affected every opponent he ever met.

Moments later, Walcott tried his first serious left hook and Louis demonstrated the duck. “Bend forwards at the waist, ducking his blow. As soon as you have ducked his blow, straighten up and at the same time counter with a blow to your opponent.”

Louis pulls this counter off beautifully, following a left uppercut to the body with a clubbing right hand around the back of Walcott’s head as Jersey Joe, already rocking a little, tries for his own duck. He doesn’t quite make it and backs up before unveiling the two-step that would cause Louis trouble all night, going away and coming back with a punch (usually a right), one big, horrible feint that Louis will fail to unpick in either fight. Later, swarming Walcott back to his own corner, Louis comes square and continues to throw blows even as Walcott blocks them on his gloves. Here we see the elemental weakness in the Louis defence—it is all but abandoned when he is in the full flow of an attack. Most offensive machines share this weakness. It is born of the absolute surety that exists in this extremely rare breed of fighter that they can outpunch any opponent, and that exchanges are therefore to be sought.

After going back to his boxing in the second, Louis shows a nice parry in the third. The champion’s curious habit of occasionally keeping his gloves tightly knitted at his chest is not entirely a matter of preparing his offense; it also allows him to move the “unit” the two gloves create up or down to catch straight blows that do not leave the opponent available for a counter. Nor does How to Box stress counterpunching after blocking blows. On occasions where the guard is made mobile to block opposition punches, the priority seems to move over to defence, perhaps the reason Louis did not use this strategy often. He can be seen primarily as a slipper and ducker of punches rather than a parrying or blocking fighter due to the lack of natural countering opportunities these earlier methods provide when compared to the latter, although such opportunities can of course be engineered. Early in the ninth Louis did exactly that. As Walcott moved forward and fired two-handed, Louis showed good flexibility, lifting his forearms which worked as an additional guard as Louis performed the block as described in How to Box:

“As your opponent leads, turn your body…If your opponent leads with a blow to the chin, use your shoulder to block it.”

Louis turns with this two-handed attack, tucking in his chin and lifting the relevant shoulder on each turn and when to his own surprise, Walcott “pops up” behind these shots right in Joe’s kill zone he improvises a pivoted hook which catches Jersey Joe on the mouth, helping him win the round.

In the fourteenth he can be seen parrying a Walcott jab and then firing off his own, not quite generating a counter but using his defence to neutralise a rare Jersey Joe lead before taking advantage and landing his own punch.

The fifteenth round of Louis-Walcott I may not be a round that in particular brings to mind matters of defence as Walcott ran and Louis chased him, but actually it is one of Joe’s better defensive rounds. He parries a Walcott jab in his very first action and slips two more before throwing his first punch, a left hook which glances off Walcott’s head. Louis is trying to box noticeably closer to Walcott now and his defence is paramount. Walcott spent most of the final round retreating and flashing up unpredictable punches when cornered or desperate, but Louis deals with most of these before firing back. Mobile and hard to hit, Louis demonstrates the truth of Johnny Ray’s statement of 1941 and his own immortal line before the Louis-Conn rematch: they can run, but they can’t hide.

The decision for this fight was by far and away the most controversial of The Bomber’s career and to this day the word used to describe it is “robbery.” For as long as we are discussing the fight, I have decided to take a brief look of my own at what seems at times to be established fact.

The 2012 Manny Pacquiao-Timothy Bradley fight will be, for many, the benchmark robbery for a generation. This is a result so seemingly without explanation that of the one-hundred and twenty-five media sources I have seen produce a scorecard we have one-hundred and twenty-one scoring in favour of Pacquiao, three scoring in favour of Bradley, and one scoring the fight a draw. That is a ratio of around about 1:30 against those seeing the fight any other way than a win for Pacquiao.

The Pittsburgh Press conducted a ringside poll of writers at the venue the night Louis decisioned Walcott and whilst the majority, twenty-four, had Jersey Joe the winner, some sixteen had it for Louis. This is a ratio of 2:3 against.

One media source reports a Bradley win for every thirty polled.

Two media sources report a Louis win for every five polled.

The point is not that Pacquiao was robbed and so Louis was not, the point is that those who did not see a win for Pacquiao in the first Bradley fight can be dismissed as statistical anomalies—they either made mistakes or sat in a corner of the stadium that would always give birth to a strange scorecard. In the case of Louis, he is backed by sixteen boxing men who know the fight game. If we include the judges amongst those polled, the difference between those who see it for Louis and those who see it for Walcott starts to look more negligible.

The widest media scorecard I have been able to source for Louis-Walcott was the AP card which had it 9-5-1 for Walcott. I was unable, as a primary source to uncover more than three ringside card that had Walcott winning any more than eight rounds. Those who stood in judgment over Louis in a surprisingly rabid press that following week typically did so based on a scorecard provided for them by a ringside reporter that had Walcott winning only six, seven or eight rounds. This is exactly what almost every single ringsider has Louis scoring.

But most interesting to me were the reports made by the two sources which, rightly or wrongly, hold the most weight in my mind when it comes to deducing the reality where close, un-filmed fights are concerned. The New York Times described Louis as having been “out-thought” and “generally made to look foolish,” but the newspaper also scored the fight for the champion because he had “made all the fighting, did most of the leading and, his two knockdowns notwithstanding, landed a greater number of blows.”

Nat Fleischer, scoring for The Ring, also saw it for Louis.

Louis, unquestionably the puncher in the fight, landed more punches according to the Times. Whilst the newspaper men ringside tended to believe that Walcott had won, there were many who felt that the exact opposite was the case, including the men who mattered. Referee Ruby Goldstein scored it 7-6-2 for Walcott, judge Marty Monroe had it 9-6 to Louis and judge Frank Forbes had it 8-6-1 for the champion.

The highlights we have available to us seem inconclusive with neither fighter really emerging as clearly the superior of the other. In the rounds I have used to describe the Joe Louis defence, one, two and four can be scored for Walcott and three, nine, fourteen and fifteen for Louis.

But even if we had the entire fight, all we would have is a modern eye trying to interpret a fight set in 1947 with their respect for the title, their heightened appreciation of aggression and disdain for retreat.

Louis was the aggressor, the puncher, the champion, and according to at least one reputable source the busier man. More than that, there were few ringside scorecards that mimicked the degree of outrage expressed by the press.

Over the years I’ve come to suspect—just to suspect—that the decision was a reasonable one.

I feel with certainty that this was no robbery. Walcott may have deserved the nod; he may not have; but either way it was close. Why, then, the controversy? It is a fact that the crowd booed Louis from the ring. This has lent credence to what has become a truth by repetition. Perhaps, like Louis himself, they were disgusted with the champion’s performance (disgust, according to Joe, that caused him to attempt to leave the ring before the verdict was even read). More likely, they had seen Louis bamboozled by an opponent that had seemed one step ahead of him throughout. But fights are not and were not scored upon aesthetics. If Louis was out-landing Walcott and enough of those punches carried enough vim to impress two of the three judges, Joe’s job was done.

Finally, the fight continued to garner attention in the press because the method for scoring boxing itself was on trial. Whilst Walcott had been awarded points for his two knockdowns in rounds one and four on the supplementary system, they had in reality only gained him two rounds on the cards and whilst judge Forbes actually awarded Louis more rounds, he awarded Walcott more points. When there seemed even a hint of a chance that the decision could be overturned on a technicality (it was claimed that Forbes should have reversed his decision based upon general impressions, permitted in a case where a judge awards more points but fewer rounds to a given fighter) the controversy continued to burn.

And it would burn until Louis doused it with an eleventh-round knockout of Walcott some six months later. But I think he deserved his win of December 1947, too, or at least I don’t consider that he was firmly beaten as the legend says. It was a close fight—so close that perhaps even a handful of punches could have turned it.

For Louis, then, his defence would at least once prove to be as important as his offense. Had Walcott landed even one more punch in the right round, perhaps Louis would have been a two-time champion of the world instead of the most dominant world champion in history, as he remains.

In the sixth and final part of this technical analysis we’ll take a closer look at this champion at his very, very best.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering the Under-Appreciated “Body Snatcher” Mike McCallum, a Consummate Pro

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

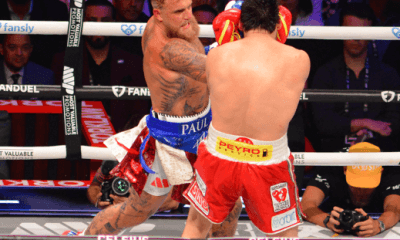

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

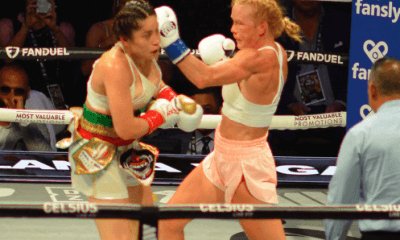

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books