Featured Articles

B-Hop’s Latest Hall of Fame Extends Beyond the Ring

B-Hop’s Latest Hall of Fame Extends Beyond the Ring

Thomas Wolfe’s celebrated novel, You Can’t Go Home Again, published posthumously in 1940, paints a rather bleak picture of a fledgling author who writes of the hometown he left years earlier but still mostly remembers with fondness, although his literary return to his roots is greeted with menacing letters and death threats from the town’s residents who don’t like his not-always-complimentary takes on the place where they still live.

In legend and lore, Philadelphia is a tough city that infrequently grants its love, especially to individual athletes or those who wear the colors of its local teams, and only then with large dollops of show-me skepticism. It isn’t enough just to be from Philly or to have arrived as a hired mercenary; in the City of Brotherly Love, it is necessary to earn civic affection through hard work and an absolute commitment to a common cause that transcends place of birth or any previous stops along the way.

Joe DeCamera, the sports-talk radio host who served as master of ceremonies for Thursday night’s 20th annual induction ceremony of the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame, acknowledged as much when he offered his opinion that James Harden, a would-be major cog in the unfulfilled championship aspirations of recent 76ers squads, would never have a seat at the dais for a future enshrinement because the star point guard, traded to the Los Angeles Clippers two days earlier, simply did not “get” Philadelphia, nor did Philly “get” Harden, a chronic malcontent who was with the team for only 79 regular-season games (and 23 playoff contests) in less than two full seasons.

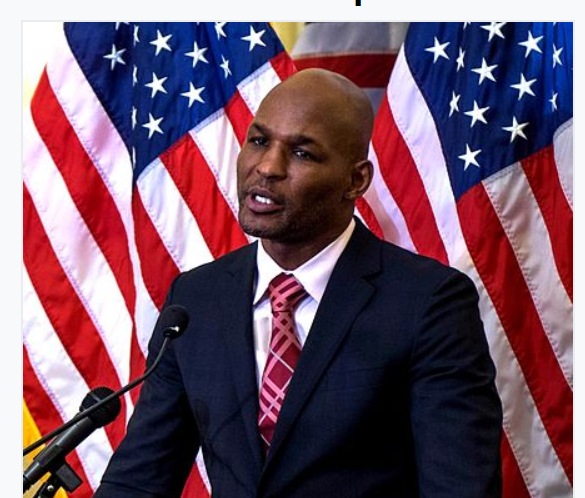

Former middleweight and light heavyweight champion Bernard Hopkins, unlike Wolfe’s George Webber character in You Can’t Go Home Again, doesn’t have to worry about an unwelcoming return to Philly because, well, he never really left. Although B-Hop still maintains a residence in Delaware, it is within the Philadelphia metropolitan area’s footprint, and he also has a lavish condo in Philly overlooking the Delaware River, befitting someone who has accrued so many professional successes. He is an inductee into the International, Philadelphia, New Jersey and Atlantic City Boxing Halls of Fame, but the one that took him to its collective bosom Thursday at Live! Casino & Hotel in South Philly, a stone’s throw from the stadiums and arenas where the Eagles, Phillies, Sixers and Flyers play, puts him not only in the company of such cherished hometown fighters as Joe Frazier, Tommy Loughran, Joey Giardello, Matthew Saad Muhammad, Jeff Chandler and Meldrick Taylor, but with some of the team-sports heroes of his youth, the ultimate accolade for someone who continues to wear his pride of Philadelphia’s intermittent sports competitive successes on his sleeve.

“It’s 2023 and to be recognized again at this time in my life (Hopkins is 58) and in my hometown is right up there with any honor I’ve received in my career,” B-Hop said before he took his place at the head table in the Live! Event Center. “This is the cherry on top of four scoops of vegan ice cream. You got baseball greats, football greats, basketball greats. And, of course, boxing greats. It’s a whole bunch of people who did unique and extraordinary things.

“One thing about Philly, you cannot just walk into an honor like this. You have to earn it from a generation of tough fans, maybe a couple of generations worth.”

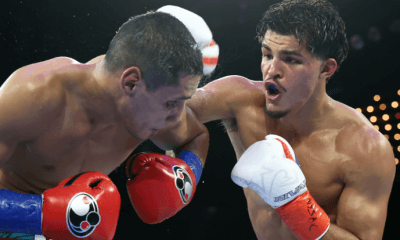

Hopkins’ appreciation for being viewed as not only an iconic Philadelphia boxer, but an iconic Philly athlete regardless of the sport, is hardly a newly minted revelation. On Oct. 9, 2004, 19 days after he knocked out Oscar De La Hoya to become the first middleweight to fully unify the division title in the four-belt era, Hopkins was the man of the moment in a parade down North Broad Street, from the front of the legendary Blue Horizon to City Hall, where he was praised as one of the city’s sporting treasures by then-Mayor John Street. An estimated 10,000 Hopkins fans lined the parade route, which might seem a bit skimpy in comparison to, say, the Eagles’ multimillion-celebrants parade after they won Super Bowl LII, a 41-33 conquest of the New England Patriots on Feb. 4, 2018, but it was nonetheless historic. Longtime Philly boxing promoter and local boxing historian J Russell Peltz, also an inductee into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame (Class of 2020), noted that it was the first such parade held for a boxer since 1939, when thousands of Italian-Americans lined South Broad Street to cheer heavyweight contender “Two-Ton” Tony Galento, a native of Orange, N.J., who was in town for a bout with Lou Nova. In his previous bout, Galento had knocked down heavyweight champion Joe Louis before being knocked out himself.

“It’s an emotional thing for me to be recognized in my hometown,” Hopkins said before the parade in his honor began. “There are so many great athletes and fighters in Philadelphia – legends, really – who never got anything like this. It’s beyond my wildest dreams.”

So moved by the emotion of the moment when he was called to the microphone by DeCamera, Hopkins, whose responses to even the most innocuous question from a member of the media can result in a 20-minute soliloquy, that he required less than one full minute to express his gratitude to be joining the PSHOF. To longtime observers of B-Hop, it was like whittling down Tolstoy’s War and Peace to a one-page synopsis from a Cliff’s Notes. Then again, the career gists of all of the inductees in attendance were shown beforehand in well-crafted videos that left few stones unturned.

Truth be told, Hopkins’ historical milestones are so numerous and impressive that it was as inevitable as a morning sunrise that he would pass muster with the PSHOF selection committee. Despite a late start to his boxing career, the result of an armed robbery committed as a teenager that landed him behind bars for 56 months, his 20 successful middleweight defenses (since matched by Gennadiy Golovkin) were a division record and he became the oldest fighter to win a world championship when he won a light heavyweight title, the IBF’s, by outpointing Karo Murat over 12 rounds on Oct. 26, 2013, in Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall. So fantastically fit was Hopkins that, even when he was nearly 52, he still remained a world-rated fighter.

“Bernard Hopkins is as close to a perfectionist with nutrition (hence his remark about vegan ice cream) as anyone I’ve ever dealt with,” said renowned physical conditioning guru Mackie Shilstone, who helped B-Hop (then 41) bulk up the right way from the middleweight limit of 160 pounds for his unanimous decision over stellar light heavyweight Antonio Tarver on June 10, 2006.

The 16-member PSHOF Class of 2023 increases the total number of inductees to 217, just 14 of whom have ties to boxing. It says much about how high that bar is set that such cherished Philly main-eventers as “Bad” Bennie Briscoe, Eugene “Cyclone” Hart, Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward and Willie “The Worm” Monroe remain on the outside looking in (Briscoe, Hayward and Monroe are deceased.)

In addition to Hopkins, other notable Philadelphia athletes and coaches getting their call to the hall included former Villanova basketball coach Jay Wright, who guided the Wildcats to NCAA championships in 2016 and 2018; Eagles standouts Jeremiah Trotter and Irving Fryar; former Phillies owner Bill Giles; former Flyers defenseman Joe Watson, who helped the team to win Stanley Cup titles in 1974 and ’75; Phillies catcher Carlos Ruiz, an important member of the team’s 2008 World Series champions; Olympic long jumper Carol Lewis, younger sister of track and field legend Carl Lewis, and jockey Tony Black, who was on board 33,964 mounts during his long career, during which he brought home 5,211 winners.

—

Bernard Fernandez, named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Observer category with the Class of 2020, was the recipient of numerous awards for writing excellence during his 28-year career as a sports writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. “Championship Rounds, Round 4,” the fourth installment of Fernandez’s four-volume anthology, is now out and available via Amazon and other book-selling outlets.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision